Identity politics loom large at the African Union (AU). As some of our writers show in this edition of Africa in Fact, many Africans still do not know what the AU actually is or does, other than that it is housed in a glitzy Chinese-funded building in the heart and heat of Addis Ababa. Since its inception there in 2001, there has been a push to make the AU more real, both for African states and citizens. Some might see this as a personalisation of the institution. However, much more mileage needs to be clocked before any fruits of this consolidation can be enjoyed.

The AU prides itself on its lineage of descent from the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which was set up on 25 May, 1963, to represent newly liberated African countries, promote African sovereignty and do away with minority rule. With the fall of the last bastions of colonial power, the OAU was ushered out and the AU welcomed in under the pen of Thabo Mbeki on 9 July, 2002. With it came high hopes and aspirations for enhanced governance across the continent.

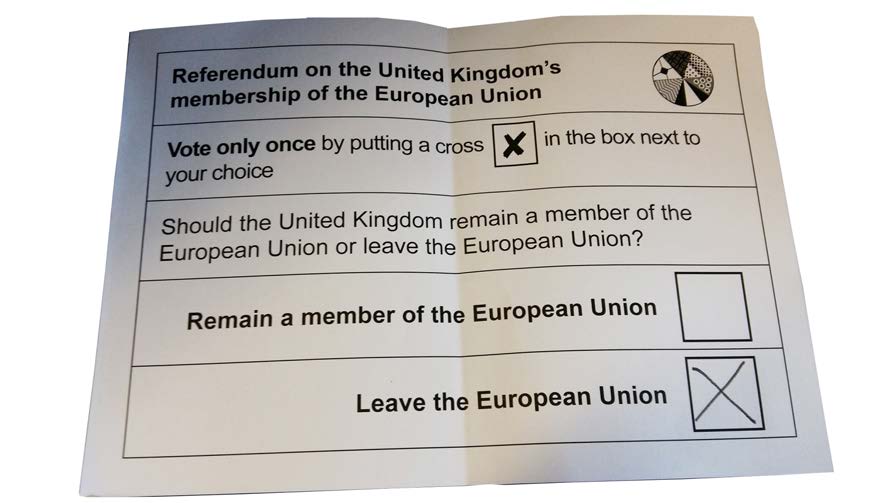

However, some critics have said that the AU is just another mock-up European Union (EU), and Afro-scepticism has since become the default position. Recently, the scepticism has apparently been supported by Britain’s impending departure from the EU, known as “Brexit”, which showed the limits of regionalism, and the election of Donald Trump, which caught the world off guard. Both of these events raised questions of media spin and hidden agendas that continue to perplex analysts. However, it is clear that in some political quarters, regional unions are neither a priority nor a panacea for the world’s problems. Bilateral relations between countries are coming back into fashion with a vengeance.

This issue of Africa in Fact provides a range of perspectives on the AU. The organisation is still dependent on foreign powers (among them, Britain, China, the US) for its funding, but the AU is planning to change this. The AU’s technical challenges with regard to peacekeeping, as well as its capacity-building for integration, also need attention. As ever, political will and sectarian interest remain problems, given our diverse and heterogeneous African societies. And the leadership of the institution under its most recent Chair, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, had raised questions, with her energies apparently more often directed towards her own country and political life there. At the same time, though, the AU has booked some successes, among them in combating female genital mutilation and child marriage.

Clearly, the idea of building community must take centre stage in any discussion surrounding the AU. For example, GGA recently hosted a Risk, Extraction and Ethics workshop attended by multi-laterals, chambers of mines, oil and gas majors, mining houses and a range of cross-sectoral stakeholders. A vigorous debate about the African Mining Vision (AMV) revealed the importance of input, which is presently lacking, from sub-regional bodies or Regional Economic Communities (RECs), such as the East African Community, the Economic Community of West African States, and the Southern African Development Community. These bodies could provide a critical link between the continental vision and each Country Mining Vision (CMV), although they are often constrained by budgetary concerns.

Much as it warms us to see the growth of a unified and a growing continental body, an effective role for the AU can only be solidified and advanced to critical mass by achieving greater regional cooperation between the member states of the RECs. Innovations such as the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) should be celebrated, but they will fail unless compliance is enforced. Unfortunately, the AU’s lack of appetite for a role as continental watchdog and law enforcer has been evident of late, as shown by its tolerance of a number of crackdowns on democratic principles and freedoms around the continent.

The same could be said concerning the implementation of international law. The flagrant defiance of states of accepted international practice, especially when indicted war criminals are involved, shows that something is rotten in the “union” of Africa. Of course, it is evident why certain old boys want to leave the International Criminal Court; they want immunity from prosecution for their chronic rape, pillage and plunder of the continent they call home. In so doing they set a very poor example. You too can face 783 corruption charges and sleep easy at night knowing that good governance rests safely in your capable hands.

Since it is the start of a new year and lest we become downbeat, let me leave you to peruse the contents of this edition of Africa in Fact with one main thought in mind. The AU can be seen as a germinating seed of democracy on the continent. We have also referred to its importance for continental solidarity. But key to both are the ability to build relationships and promote a sense of community. These remain lofty ideals, as our writers indicate, but there appears to be more movement in the right direction. Long may it last.

We at GGA are actively pursuing community-building in our own organisation. To become a hub for good governance, as of January 2017, we are introducing a Good Governance Africa membership model, comprising three tiers: premier (Green), institutional/organisational (Red) and individual (Grey) (see inside front cover). These membership tiers offer different levels of access to our publications, programmes and services, which include bespoke research, book launches, training and workshops at our new home at the Mall Offices in Rosebank, Johannesburg. We do hope that you will join us and become partners on this mission.

On behalf of my fellow executive directors and the entire GGA team, may we wish you everything of the best for a bright and blessed 2017 and many hours of happy reading, researching and engagement with us.

Alain Tschudin

Executive Director