One of the largest immunisation drives in Africa’s history is about to commence and African governments must urgently ramp up their readiness, both on the front end with the administration of the vaccine as well as on the back end with supply chain and distribution logistics.

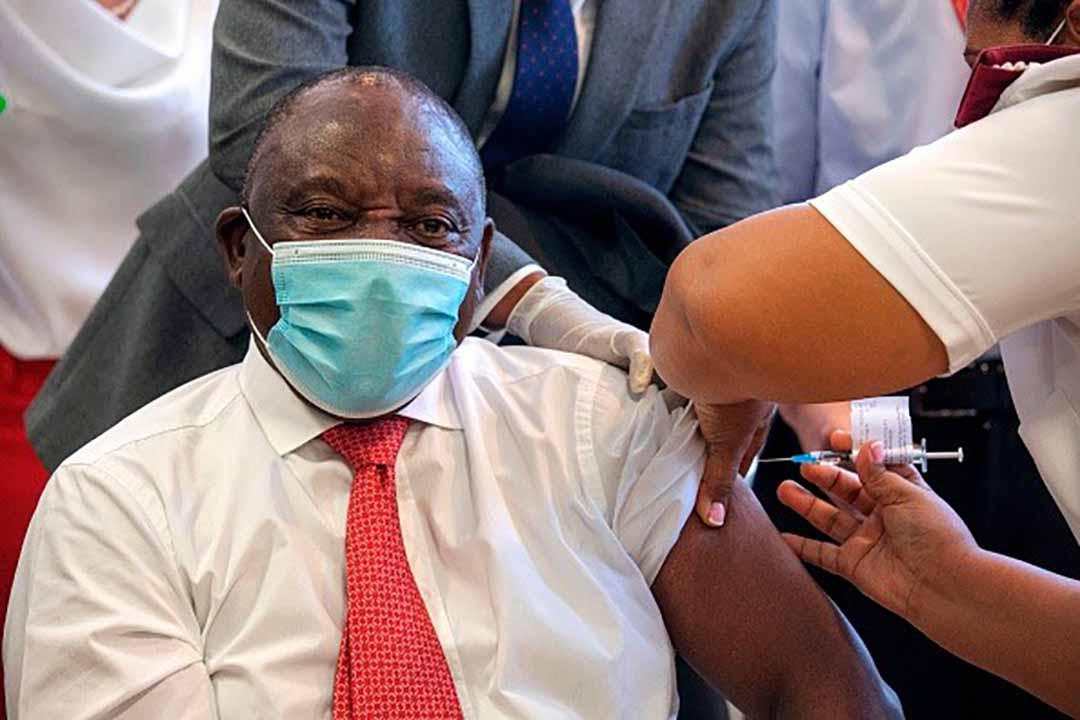

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa is inoculated with a Covid-19 vaccine shot at the Khayelitsha Hospital in Cape Town on February 17, 2021. (Photo by GIANLUIGI GUERCIA / POOL / AFP) (Photo by GIANLUIGI GUERCIA/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

The economic impacts of COVID-19 are threatening to undo years of economic progress in Africa, with the worst recession expected in close on 25 years. Health systems in Africa are particularly overstretched, and the social measures (lockdown) to limit transmission are placing a heavy socioeconomic burden on vulnerable populations in particular. Is the vaccine the way out? Only if readiness can be rapidly and universally ramped up.

According to a World Health Organization (WHO) analysis, Africa is not ready for COVID-19 vaccine distribution as indicated by the Vaccine Readiness Assessment Tool received by all 47 countries in the WHO African Region.

The development of a safe and effective vaccine is merely the first step in a successful rollout. According to the COVAX facility, only 49 percent of African countries studied have identified the priority populations for vaccination and have plans in place to reach them; 44 percent have coordination structures in place; 24 percent have adequate plans for resources and funding; with little data collection and monitoring tools in place and insufficient plans for effective communication in order to build trust within the communities.

Historically, Africa has largely been a passive recipient of vaccines developed and tested elsewhere. However with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, African researchers and experts have played an active role in the study of the virus and in clinical trials of the approved vaccines. The major motivation for COVID-19 vaccines being evaluated at an early stage in South Africa was to generate evidence in the African context for how well these vaccines work.

Efficacy and side effects

Normally, vaccines require many years of design, testing and additional time to produce to scale. Vaccine development begins with basic laboratory studies on the virus and its interaction with body cells. The results inform pre-clinical studies in which the vaccine is tested on animals and its safety recorded. Reaction of the animal’s body cells are documented and inform the four phases of clinical trials in humans. The South African COVID-19 vaccine trials commenced in June 2020, ranging from 4 sites to 31 sites, primarily with a four phased approach. Some of the trials revealed the following notable findings:

On the one hand, the Novavax Vaccine appeared to work well on the COVID-19 virus, however was not as effective on the B.1.351 variant against which the vaccine’s efficacy was evaluated in South Africa. An early analysis in Britain found that the two–dose vaccine had an efficacy rate of nearly 90 percent. But in a small South African trial, the efficacy rate dropped to 49.4 percent; early signs therefore indicate that the vaccine is not as effective against the fast-spreading South African variant as it is against the ordinary strain.

On the other hand, the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines use advanced technology based on RNA and require storage at -70 and -20 degrees Celsius respectively. That makes their distribution and storage a logistical challenge, especially in countries without the requisite storage facilities. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is not particularly suited to African contexts, as infrastructure problems make it impossible to store the vaccine at the required temperatures.

Over and above the vaccine’s efficacy, close attention needs to be channelled to the side effects of the vaccine, particularly for individuals with comorbidities. Typical vaccination reactions have been reported after administration of the BioNTech-Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca and the Sputnik V vaccines. During the Novavax trial in South Africa, which found the vaccine to have a 49.4 percent efficacy overall, the company reported that about 6 percent of the trial’s participants were positive for HIV, and for those who were not HIV positive, the vaccine had a 60 percent efficacy.

Herd immunity

Vaccination can help achieve herd immunity if a critical mass of people are vaccinated (and maintain immunity). According to estimates, herd immunity for COVID-19 will be achieved when more than 60% of the population is vaccinated. To achieve the goal of vaccinating at least 60% of the population, Africa will need approximately 1.5 billion vaccine doses which at current estimates could cost between US$ 8 billion and US$ 16 billion – excluding the additional 15 to 20 percent cost for injection materials and the delivery of vaccines. In South Africa, the target is to vaccinate 67% of the population by the end of the year (as many as 40 million people) to achieve herd immunity. South Africa has recently acquired only one million of the approximately 80 million doses needed to achieve the set target of herd immunity (for the vaccine requiring two shots for optimal effectiveness).

Getting adequate vaccine supplies is not the only challenge governments face. Anti-vaccine sentiment is a problem in several Western countries that have started the roll-out. In Norway, for example, it was reported that 33 deaths of frail and elderly were related to the of administration of the Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine. An Ipsos poll published in November 2020 found that 46 percent of French adults said they would refuse to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. In some African countries, this appears to be much less of a problem. A survey by CDC Africa and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine found that 79 percent of people in 15 African countries would be vaccinated if the jab was found to be safe and effective.

Some middle-income countries and most low-income countries face the risk of being left behind in the immunisation drive. The Economist Intelligence Unit has predicted that while rich countries will have access to proven vaccines by mid-March 2021, poorer countries may only achieve meaningful vaccine coverage by 2023. This inequality has negative implications for economic recovery in poorer countries, exacerbating the risk of economic regression.

Improving Africa’s preparedness

To maintain goodwill towards vaccination and ensure its efficacy, it is essential not only that all African countries be involved in vaccine trials, but that African governments address their existing challenges. Critical issues that could impede African countries’ preparedness for equitable delivery of the highly anticipated vaccines include funding gaps, weak health systems, poor supply chain infrastructure and undefined eligibility and prioritisation criteria to ensure that the most vulnerable populations receive access as soon as possible.

Individual country level efforts should be focused on both the front end and back end preparedness for the COVID-19 vaccine. This includes the determination of eligibility criteria; administration of the vaccine by skilled and trained healthcare workers; the development of robust supply chain and distribution logistics; tracking of immunisation results and documenting of side effects and finally the availability and sustainability of the vaccine in the long run.

Africa must continue its concerted efforts to jointly respond to the pandemic – including development, production and distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine. African governments are encouraged to be more efficient in the allocation of resources during this time, not only focusing and channelling resources to vaccine supply and distribution but also ensuring that minimal socioeconomic disruption occurs in order to avoid future poverty-related impacts of potentially ill-informed or arbitrarily imposed lockdowns. For example, non-pharmaceutical interventions (in the form of lockdowns) should be subjected to the same kind of rigour as pharmaceutical interventions (vaccines).

African governments would be well advised to reassess some COVID-19 intervention policies like policing lockdowns that require large amounts of state resources. Allocating a portion of these resources towards resuscitating the strained socioeconomic environment may provide more optimal results. Moreover, addressing the backlog of HIV and TB testing, and building a concerted effort to reduce non-communicable diseases, may prove more effective in the long-run than lockdowns in reducing excess deaths from COVID-19. While the vaccine may be the resolution to the global health crises, the food security crises that have been exacerbated by the pandemic still needs to be addressed, particularly in developing countries.

It is apparent that the vaccine ‘alone’ is not the way out for Africa. Rather, a combination of good governance of resources and proactive COVID-19 intervention policies enabling the recovery of the socioeconomic environment are also crucial factors for Africa’s way out of the crisis.