Exploited and marginalised by the communities around them, Zimbabwe’s San fight an uphill battle for survival

In May 2013, Zimbabwe’s former president, Robert Mugabe, caused controversy when he said the country’s San community, commonly known as Bushmen, had “a culture which (wa)s very resistant to change”. The Bushmen, he claimed, just wanted “look after cattle and be in the bush”.

Mugabe was speaking at the memorial service of former vice president John Nkomo, whose rural home, Tsholotsho, is in Matabeleland North, where a significant number of the San reside. Adding fuel to the fire, he said the San were “resisting education and efforts to make them more civilised”.

His comments were criticised by Zimbabweans, who maintain that the San community there is marginalised, disempowered and vulnerable. A visit to the San community’s Mgodimasili village, a settlement where about 200 people live, reveals that the community’s living conditions still lag behind those of other Zimbabwean communities and ethnic groups.

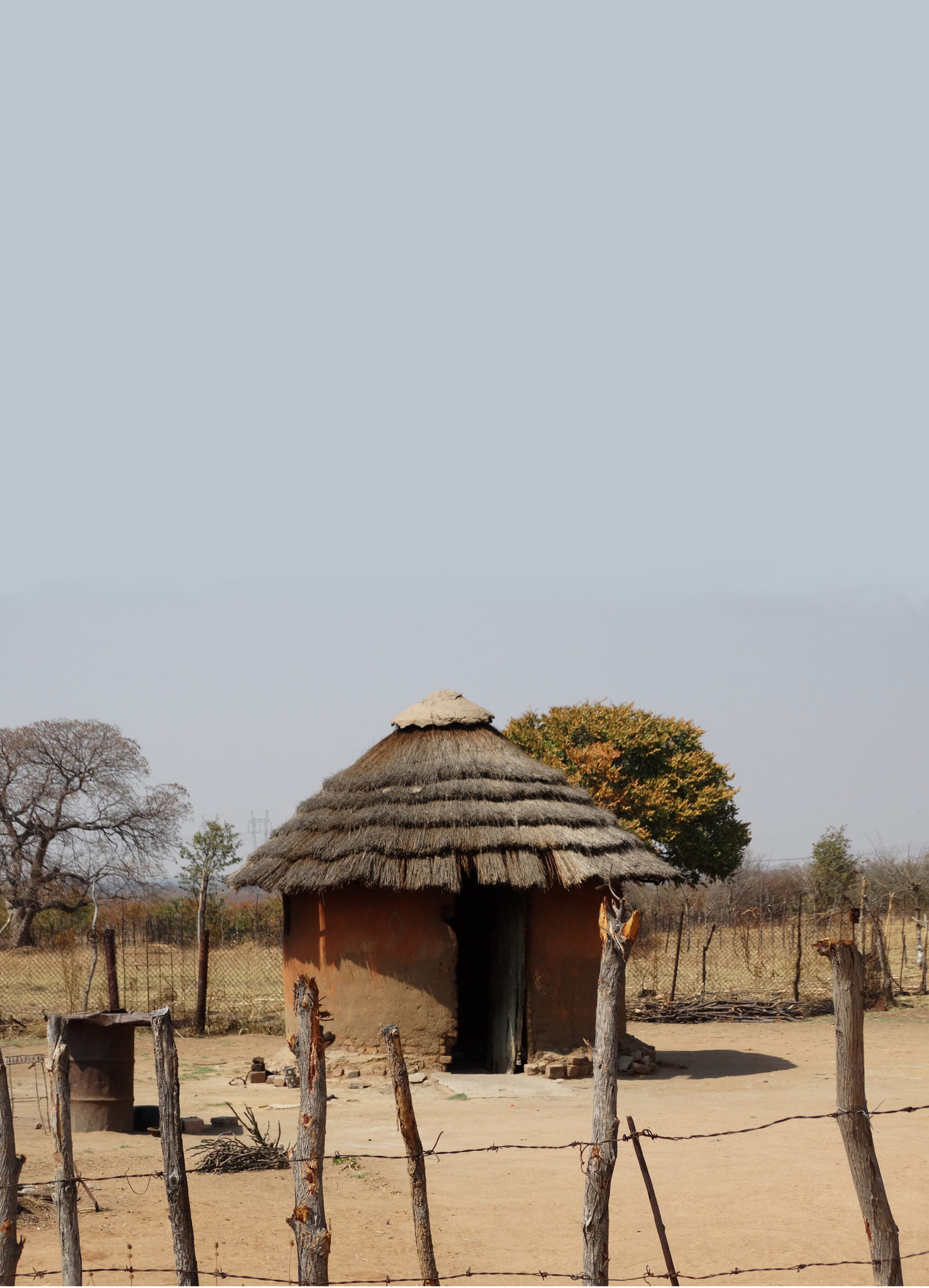

Villages exist on what they can get doing menial domestic jobs. Photo: Owen Gagare

The bulk of the San community in the village live in dilapidated thatch mud huts. They survive mostly on menial domestic jobs such as herding cattle, for which they are often paid very little, or only “in kind” with food. Most members of the community also do not have any identification papers. Yet only a few kilometres away the neighbouring village of Tjitatjawa – dominated by Ndebele speaking people – boasts neat houses with corrugated iron roofs. The unequal living conditions of the two communities could not be more stark, despite their close proximity.

In an age when most Zimbabweans are hooked on e-technologies, many members of the San community still cannot read or write. Some, especially the young, don’t know their own language, Tshwao, having been forced to adopt the languages of neighbouring communities. For thousands of years the San survived by hunting and gathering, but in the 1920s their lifestyle was disrupted when they were forced to move from their original territory in Hwange to make way for the Hwange National Park.

Their chances of survival have been limited by lack of education. Formal education is a new phenomenon among the Zimbabwe San. At present, some 248 San children attend Early Childhood Development classes up to Grade 2. This was not the San’s choice, villagers say, but due to government neglect. Siwatshi Moyo, a member of the San community, says that most community members are unemployed, and cannot afford to send their children to school.

“Most of us have no means to earn money,” he told Africa in Fact. “We cannot afford to pay fees, and that is why our kids spend the whole day roaming around doing nothing. The desire to send children to school is there but we do not have the ability.” He added that without education, most members of the community were caught in a cycle of poverty.

Madlela Maphosa, the village headman, said he wanted the government to build a school specifically for the San community in Tsholothso and ensure that enrolment was free. Many people from the community would be keen to take up such an opportunity. “The government can also provide us with jobs like building bridges and dams so that we can have money to pay fees.”

Mbuso Fuzwayo, a programme coordinator with Ibhetshu LikaZulu, a Bulawayo-based civic group, also believes that the government should offer the San free education. “The government should have a deliberate focus of trying to modernise the San; one way is to offer them free education,” Fuzwayo said. She added that the deficit in their socio-economic status was due to the San being “a smaller group of people in a bigger group of people (in) Matabeleland who have been marginalised”.

This year, the government opened a new primary school in Mgodimasili to cater for the San community. Previously, San schoolchildren had to travel more than 10 km to get to the only primary schools in the area, Butababili and Skente. But though there is now a school closer by, for many the problem of fees remains.

In February this year, Matabeleland North acting Provincial Education Director Jabulani Mpofu told public media that getting the community to pay fees was a challenge. Given the widespread reluctance to pay school fees, the government would have to consider an “advocacy” programme, he said. Many residents thought it “unnecessary” to pay fees, he told the media. “We need more stakeholders to assist us in such an advocacy programme.”

Mpofu was referring to stakeholders such as non-governmental organisations. Plan International Zimbabwe, an international NGO with regional and country offices, including Zimbabwe, helped to fund the construction of the school.

Davy Ndlovu, project manager with Tsoro-o-tso San Development Trust, an independent organisation that conducts research on San culture, said the new school was “a vital step” in educating and empowering the San community in Tsholotsho. But, he added, other ways of funding schooling for the community would be necessary.

Mgodimasili village headman Madlela Maphosa Photo: Owen Gagare

“Most of the (community) are indeed vulnerable and cannot afford to pay fees,” he told Africa in Fact, “but at the same time, the school needs money to run effectively.” A statistical study conducted by the trust in 2013 revealed that a total of 96 San children were in school in the district. About 90% were in grades between 0 and 3, while about 10% of them proceeded as far as Grade 5. No San child had reached Grade 7, all of them having dropped out between Grades 3 and 5. According to the study, their reasons for dropping out of school included an inability to pay fees, a lack of food at home (which forced them to join their parents in hunting for food), lack of proper clothing, bullying and intimidation.

“The San in Zimbabwe have been neglected for a very long time,” Ndlovu said. “In Zimbabwe we have just two San community members who have completed their advanced levels. In other countries in the region, such as Botswana and Namibia, you find some members of the San community with masters degrees or doctorates, while here just five have managed to complete their ordinary levels.”

Most dropped out of school at primary school level, and most members of the San community say they have never attended school. Nkosiphakade Sibanda, a young San woman who I encountered carrying kindling, had only gone as far as Grade 2.

Members of the San community believe their neighbours are taking advantage of their abject poverty and hunger to exploit them. In many cases, San cattle herders are paid less than 100 South African rand per month.

“Those people (from neighbouring villages) cheat us. They treat us as slaves. It’s sometimes better to beg for food,” Artwell Moyo, a villager said. According to Maphosa, the village head, many of the San people’s problems are due to the fact that they have no one to represent them and protect their interests. “We are orphans,” he said.

Ndlovu agreed that communities neighbouring the San often took advantage of their softness to exploit them. “There are cases where members of the community have herded cattle for up to five years without being paid, on the understanding that they will be given a cow at the end of the period. But when the time arrives, the person chooses to disregard the agreement,” Ndlovu told Africa in Fact. “In most cases the San just walk away because they are not quarrelsome people.”

The 2013 Tsoro-o-tso San Development Trust report, My Culture, My Pride: Reclaiming the Tjwa Cultural Identity, reveals that many San youths in Tsholotsho district also feel that they must hide their identity and gain acceptance as Ndebele or Kalanga (like the Ndebele, a group originally from South Africa). “This self-denial is a culmination of identity loss and is due to discrimination by their Ndebele and Kalanga neighbours, who also dominate local community leadership positions,” the report reads in part.

Most present-day San members speak Kalanga and Ndebele. A few older San still remember the Tshwao language but do not use it in their day-to-day interactions. Schools use Ndebele as the vernacular language of instruction and examination. Ndebele is the dominant vernacular in the district.

Although the new school in Tsholotsho is a step towards the San community’s empowerment, one gets the feeling they have a long way to go before they are truly empowered. Without education, the community’s cycle of poverty is likely to persist. At the same time, their language, Tshwao, is threatened with extinction. NGOs such as Tsoro-o-tso San Development Trust are compiling records and writing books in an attempt to preserve the language. But the community will likely need government support for its language, too.