Reimagining US-Africa relations

Even before Joe Biden’s presidency could be confirmed by the US Congress, the debates surrounding the renewal of the country’s Africa policy were gaining momentum. Given the chilly reception that Africa had to contend with under the Trump administration, the Biden-Harris government was seen as helping to turn the tide.

While the possibilities that a Biden government could represent a reinvigoration of the relationship, at the same time there were undercurrents in the discussion which hinted that US-Africa policy could not continue as usual. This was because the US engagement with Africa had become indecisive prior to the Trump presidency, when the traction of China and other emerging actors had become a strategic point of competition and rivalry.

Nevertheless, Biden’s election as the 46th president of the United States was as much about bringing the US back into Africa as it was about Africa returning to the US’s ambit of tactical influence. This article examines such an interpretation against the backdrop of how such a renewal of the US-Africa engagement will define the relationship beyond just a reaction to China in Africa, but also explores a policy relationship that underscored a sense of pragmatism based on an actual partnership of mutual interests.

In reflecting on what will in effect be a renewal of the US-Africa policy, the pertinent question is whether the Biden government will consider its own independent engagement with state and other political actors in Africa, instead of assuming that the relationship has to be pointed towards offsetting China’s largesse across the continent.

With the above context in mind, this commentary will examine to what extent the US-Africa relationship can be reimagined from the bilateral to the multilateral engagement. So far, the optics of the narrative have been set against the perspective that the US needs to reprise its role in the continent. As far as this may be the immediate objective of the Biden administration, this commentary will argue that in consolidating its Africa policy, the bilateral lens offers one avenue to reinvigorate the relationship and steer it towards the multilateral setting, which will afford Washington a complementary layer to advance its African engagement.

Most often in foreign policy analysis, the bilateral engagement sets the scene for the way a country will shape its interactions at a broader regional level. In the case of the US, this has more meaning and potential in informing Washington’s relations with regional economic communities and more strategically with the African Union (AU).

But the critical question is, which countries are considered as having sufficient tactical significance to reorient Biden’s Africa policy? This will depend on both strategic influence and economic trajectory.

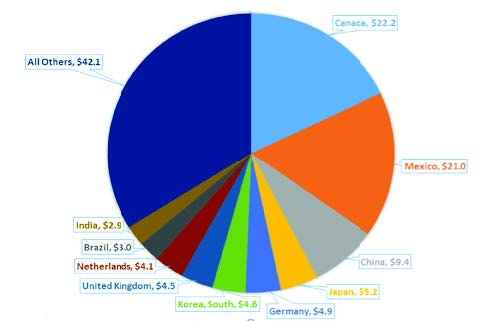

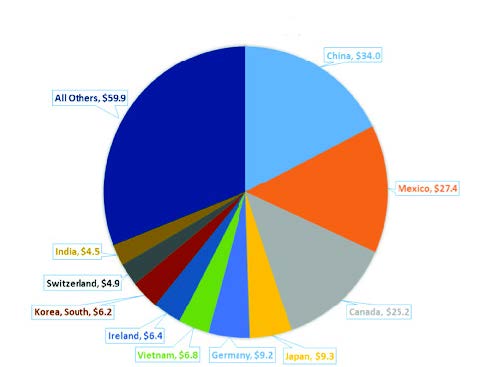

Currently, from a purely economic point of view, it is important to disaggregate the data in terms of who are the US’s major import partners and how much the US sells to Africa. Yet more than this, it is also significant to understand where Africa fits in the US’s global trading architecture. As the two figures below show, the continent has a negligible presence in the trade profile of Washington’s global economic footprint.

If we further explore US imports from the continent over a 20-year period (1997-2020), we see they have shifted from a peak in 2007/2008 to a recovery in 2011 and then a steep decline to levels well below US$50 billion, as noted in the graph below. At the same time, exports from the continent over the same period have seen a steady weakening.

Clearly, the aggregate approach to the US’s continental economic footprint seems to show a less convincing picture regarding how it will overshadow China’s presence in Africa. Perhaps what is telling is that the bilateral engagement will provide more opportunities for the US in resetting its engagement with African stakeholders at the multilateral level. For starters, thinking about localising engagements towards anchor states in regional economic communities will be a good point of departure.

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) will be the litmus test for this approach. Assuming that Vice President Kamala Harris succeeds Biden as the first female black president, the dynamics of AGOA and what defines its character and substance after 2025 will be determined by how the negotiations are advanced in this interim period of the Biden presidency. This is where a few beneficial options could be explored for both sides.

US exports, top 10 countries of destination, February 2021 ($ billions, not seasonally adjusted). Source: Source: US Census Bureau, Economic Indicators Division

The first is that the Biden administration, with Harris leading the negotiations on AGOA, could set the pace for using its convening power to start the process of engaging with African anchor countries. These include South Africa, Rwanda, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Morocco, Egypt and Ethiopia. The AU Commission will initiate the strategic dialogue of cooperation and engagement of what a post-2025 AGOA format should incorporate as its focus in upping the ante on the economic front.

US imports, top 10 countries of origin, February 2021 ($ billions, not seasonally adjusted). Source: Source: US Census Bureau, Economic Indicators Division

In this scenario, the directing of US foreign direct investment into regional infrastructure connectivity and transport projects will assist in strengthening regional economic integration programmes with a view to addressing how this will complement the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). Not only will this allow the engagement to be more consultative, but will allow the US to include a more collaborative engagement that takes into account African agency and what actually constitutes the continent’s trade and investment needs. It will also allow for a more inclusive engagement between state actors and corporate stakeholders to develop a comprehensive partnership of cooperation.

Volume of US imports of trade goods from Africa, 1997 to 2020

(US$ billions). Source: Source: US Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce

Of course, if the domestic architecture in the US shifts towards a Republican Party-led White House, then the situation around AGOA will have to be considered in this context. Therefore, to this end, the window of opportunity needs to be seized upon now if the US-Africa relationship is to be recalibrated.

The second opportunity will be to look at how AGOA and the AfCFTA can be synchronised around the creation of regional value chains. Linking the investment around regional infrastructure corridors will open up the space for both the US and Africa to identify critical gateways that can support commercial activity around regional production spheres. The corridors, however, should not be seen as only serving the purpose of exporting to the US and global market, but should also be aimed at advancing the dynamics of regional markets that will serve the consumption patterns of Africa’s growing population, and in this way, boosting inter- and intra-state African trade.

The third opening for the engagement will be to include a multi-track diplomacy tag to the relationship, where AGOA will serve to strengthen centres of innovation and knowledge hubs that will advance critical engagement on, among others, pandemic preparedness, climate action and sustainable food production. This will not only enhance the agenda on future work but also provide a platform for people-to-people collaborations and exchanges that begin with a discussion on the post-Covid architecture of a global political economy.

The final area where AGOA can serve as a significant enabler is to recognise the power of city-to-city diplomatic engagements. This is becoming an emerging space for socio-economic development finance aligned to local economic development programmes. It is an untapped market for both the US and African states to do well in shaping opportunities for young entrepreneurs, and crafting linkages with the Young African Leadership Initiative. It also represents a platform where harnessing the potential of Africa’s youth can become a critical resource in advancing digital and technological investments in respect of a green economy.

The bilateral engagement unlocks the potential for the way the US can manifest and rearrange its Africa policy. It offers pragmatic forms of engagement that are less rigid and geared towards looking at the continent outside of a macro lens.

But, indeed, the US’s positioning on bilateral engagements has to dovetail with its multilateral expectations on the continent. In simple terms, this means that if Washington seeks to refocus its efforts in Africa towards a strategic engagement, then it has to be oriented towards understanding that Africa has strategic autonomy and Washington should not view itself as the arbiter in the continent’s external affairs.

For a start, the multilateral space should not be interpreted as open season for Biden to use its arsenal based on its own form of wolf diplomacy in Africa. If this is the premise of a re-engaging policy towards Africa, then Washington is already beginning from a position of disadvantage. The primary test for Washington in its renewal with Africa at the multilateral level is to consolidate capacity and build resilience in its comparative advantage with the continent. And such an approach needs to go beyond rhetoric, congratulatory messages to an AU summit or using the continent for military bases and other vested interests in terms of security.

So what is needed?

The most basic issue that will serve to reinvigorate the US-Africa relationship is to enhance the engagement around peace, stability and development. To this end the first point of departure is to remember that democratic politics will prevail as long as Washington realises that the winds of change for democracy reside with the citizens of Africa.

Second, the electoral landscape in Africa is complex and thus the US, like any other country, would do well to support the building of an institutional architecture that is based on African principles, norms and values rather than pronouncing for a particular brand of democracy.

Third, the notion of peace and stability, while intrinsic to the notion of electoral politics, has to be understood in the context of what are the root causes of intra-interstate conflicts and tensions. It will not be in the geostrategic interests of Washington to cast the material causes of conflict in Africa in the same light as it has done in the Middle East or on its own soil. Here, peace, stability and development should not viewed through a cursory framework. Rather, they should be measured against the backdrop of the material transformation debate of the socioeconomic politics of exclusion versus inclusion.

Finally, for this resilience to be truly reflected in the recalibration of the engagement with Africa, it must also be transmuted into the way Washington embraces and prioritises the African voice and action in the global governance agenda aimed at reshaping the power dynamics of the multilateral system. It would be futile to talk about re-energising the engagement at the continental multilateral level while still enabling global conditions that hamper the continent’s integration into the political and economic affairs of the international system.

The biggest difficulty facing Washington in redefining its relationship with Africa, from a strategic autonomy perspective, is China. It seems that the Biden presidency, like previous administrations, is having a hard time trying not to chase the Dragon’s tail across the continent. By framing the narrative in this parochial way, Washington is enabling and strengthening China’s Africa policy instead of stabilising its own identity on the continent.

It is important for Washington to consider that China, like any other external actor, is also undergoing its own metamorphosis in its engagement with Africa. While Washington may construe this as an opening, it would be wiser for the Biden presidency to look at this more from the basis of deepening its capacity and resilience based on the “Africa that we the people want” rather than the wants and interests of political and economic elites.

Seemingly, Washington’s traction in Africa lies with the way the US administration pursues a mature and pragmatic engagement with continental state and non-state actors. Trying to circumvent Africa relations with other actors will be trivial. Redefining the bilateral and multilateral contours of the engagement with Africa offers Washington a more palpable roadmap for reimagining its African policy than trying to play catch-up with adversaries, and pushing back competitors.