US-Africa security relations

As the new United States administration of President Joe Biden embarks on a review of US-Africa relations, it is important to reflect on the security policies that should undergird this relationship. Although both bilateral and multilateral security cooperation feature prominently in the US’s engagement with African countries, these matters have always been opaque and shrouded in secrecy. This article suggests that there is a need for a shift in US policy to emphasise transparency in security engagement with African countries as well as more selectivity in allocating security assistance. A transparent and selective approach should reinforce the democratic governance promotion posture of the Biden administration. For their part, African recipients of security assistance should also be transparent and accountable to their citizens about the purposes of security assistance and its implications for national budgets.

Ethiopian soldier in the northern Tigray region near the Eritrean border. Photo: Maco Longari / AFP

Security cooperation benefits Africa and the US in three primary ways. First, there is broad consensus that secure states and societies are the foundations for democracy, development and prosperity. The legacy of civil wars in Africa reveals that once violence destroys the socioeconomic infrastructure that protects societies, it can take decades for recovery and reconstruction. Second, the majority of African states may, in the short to long term, never mobilise sufficient resources to achieve security without assistance from external actors such as the US. While the Cold War heightened Africa’s dependence on military support from a wide range of external powers, the security needs persisted as African countries and sub-regions confronted the spectre of civil wars, starting in the 1990s. In the post-Cold War period, the US, alongside its western allies, took on an increasingly large burden of security assistance to African countries who sought to take advantage of the new aid opportunities. Third, new and emerging security threats such as terrorism and radical Islamism have arisen in the context of weakening state capacity and porous borders that require well-equipped and resourced security forces. The convergence of these factors obligates the givers and recipients of security assistance to be more open and upfront about its purpose.

US Foreign Military Financing for Africa (FMFA) covers a wide range of programmes such as transfers of military material, tactical combat training, joint military exercises, military education for officers, and defence institution building. In addition to the Department of Defence (DOD), which administers most of these programmes, the Department of State runs its own security assistance programmes to African countries. Starting in 2005, some US National Guards have formed partnerships in capacity-building with African countries. The most notable cases are South Africa, with the New York National Guard, and Rwanda with the Nebraska National Guard.

Since the Clinton administration (1993-2001) advanced the policy of capacity-building for African militaries to participate in peacekeeping, selected African militaries have received substantial US training and equipment through programmes such as the African Crisis Response Initiative (ACRI), the Africa Contingency Operations Training and Assistance program (ACOTA), and the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), funded under the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. In the aftermath of 9/11, the US increased its counterterrorism footprint in Africa through the Pan-Sahel Initiative (PSI) and the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn Africa (CJTF-HOA), part of the US Africa Command in Djibouti. With the formation of the US Africa Command (Africom) in 2007, the US suggested to African countries the possibility of stationing it in Africa, but, with the exception of Liberia, most countries rejected this offer. Nonetheless, the majority of African countries have gradually embraced various forms of military cooperation with Africom. Even its most vociferous critics, such as South Africa, have welcomed military engagements with Africom. Some observers have noted that the command’s senior leaders frequently travel to African countries and have had more interactions with their leaders than any other officials from the US government.

Various US administrations have consistently allocated FMFA to a majority of its African allies in response to need, absorptive abilities, and other considerations. The only change came when President Donald Trump (2016-2020) did not request military assistance for African countries, with the exception of Djibouti, which hosts the CHJTF-HOA. As democracy promotion and antiterrorism became central planks in US policy toward Africa, various administrations imposed sanctions, including withholding military support to African countries they accused of egregious human rights violations and supporting terrorist groups. In the late 1990s, the US Congress enacted the Leahy Laws, which prohibit the US Department of State and Department of Defence from providing military assistance to foreign security force units that violate human rights. In the Horn of Africa, the Clinton administration blacklisted Sudan because of its support for terrorist organisations and destabilisation of its regional neighbourhood. Eritrea, under the authoritarian rule of Isaias Afwerki, was also targeted for supporting extremist groups in Somalia. In southern Africa, the US Congress imposed sanctions on Zimbabwe in the early 1990s because of gross human rights violations; these sanctions still remain despite the ousting of the Robert Mugabe government in 2017.

Sudan, Eritrea, and Zimbabwe, to some extent, epitomise US attempts to realign the values of democratisation with its military and security policies in Africa. But these are the exceptions to the broader policy, which has departed from this realignment. As a result, for the most part, countries with authoritarian leaders and a history of human rights abuses have received military assistance, especially when they have been at the forefront of counterterrorism efforts. Typically, US proponents of working with security forces in authoritarian countries have invoked the “socialising effect”, whereby the US military ostensibly inculcates the values of democracy, human rights observance and professionalism in the participating African militaries. In the long term, therefore, this inculcation helps these countries as they make the steady transition to democratic societies. The record of socialisation for better governance is decidedly mixed: while US military engagements with some African armies may have prevented them from disrupting the democratic transitions of the 1990s, there are also many cases of US-funded militaries that have been complicit in coup d’état and unconstitutional changes of government. Egypt’s military stands out for its long-standing relationships with the US military and its perennial proclivity for denigration of civilian institutions. In addition, the Malian military, which had received US training led the military coup that overthrew the civilian government in 2012.

Widespread US military support for undemocratic African regimes that have been useful in counterterrorism campaigns is evident in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. It is indisputable that terrorist organisations are a threat to the security and livelihoods that African countries cherish. This means that counterterrorism is, at heart, an objective that both the US and Africa can collectively pursue without too much contestation. However, counterterrorism efforts that hinge on indiscriminate support for authoritarian regimes invariably undermine the legitimacy of these initiatives and, even worse, fuel the constituencies that provide succour and support to extremist organisations.

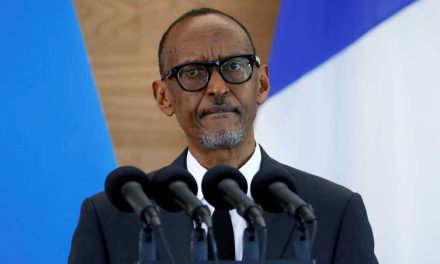

Years of US involvement with Uganda’s military and security forces in counter-insurgency in the Horn and Great Lakes regions have not enhanced their respect for democratic norms nor their responsiveness to human rights. As the February 2021 elections demonstrated, President Yoweri Museveni has consistently used Uganda’s participation in UN peacekeeping in Somalia to trample on domestic opposition and militarise society to extend his more than 30-year rule. Opposition groups claimed that Ugandan army units trained by the US military in 2014 and 2015, and deployed in Somalia, were redeployed in Kampala before the elections to intimidate them. The Biden administration needs to be applauded for its April 2021 decision to impose visa restrictions on Uganda’s security forces for their interference in the elections. This decision followed similar sanctions the Trump administration imposed on Tanzanian officials who botched the 2020 elections. These actions should signal the departure from blanket US military engagement with undemocratic regimes in Africa. But for the policy to be sustainable, the US will need to apply it consistently and impartially, particularly within sub-regions that face the same circumstances. Thus, once the US imposes visa bans on the Ugandan military, there is every reason to do the same when the Paul Kagame regime in Rwanda uses the military against domestic opponents.

The Horn of Africa has always presented a dilemma for US policy in Africa, particularly in reconciling support for democratic governance and the pursuit of counterterrorism strategies. But this is also understandable in light of the tremendous security implications of Somalia’s 30-year descent into anarchy; the emergence of Al-Shabaab in 2006 and its virulent Islamist agenda has compromised democratisation and security as values that are important for the long-term stabilisation of the region. Regional actors, including the African Union, have also prioritised the objective of military defeat of Al-Shabaab as an essential step in the creation of a functional state in Mogadishu. In the initial phase of counter-insurgency strategies, the US relied primarily on Ethiopia under former prime minister Meles Zenawi, who did not have any pretensions to democratic credentials. In the post-Meles period, the regime of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has remained a critical supporter of US policy while promoting fundamental reforms in governance at home. Before the disastrous Ethiopian military intervention to stop alleged secessionism of the Tigray region in 2020, Ethiopia was on a trajectory to become a credible regional actor the US could continue to depend upon in its efforts to stabilise Somalia.

Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki is greeted upon arrival at Khartoum International Airport outside the Sudanese capital September 14, 2019. (Photo by Ebrahim HAMID / AFP)

With Ethiopia engulfed in internal conflict, the US strategy on counterterrorism has fallen back increasingly to the CJTF-HOA, based in one of the most undemocratic regimes in the region. Although Djibouti’s authoritarian and clan-based ruling class afforded the US easy entry into the region, in the long run, there needs to be debate on the sustainability of this engagement if there are no fundamental alterations in domestic politics. In his last days in office, Donald Trump signalled an eventual withdrawal of US troops from Djibouti. This move, however, was motivated less by concerns about the regime’s authoritarianism and more about US withdrawal from endless external military forays. The Biden administration has the opportunity to refocus US security policy towards promoting both democratic governance and security collaboration. There is already a regional template that the US can draw upon: Ethiopia under Abiy had shown that regional leadership on counterterrorism can proceed alongside building domestic confidence that strengthens democratic institutions. Equally critical, in addition to fighting Al-Shabaab terrorism, the stabilisation of the Horn of Africa will require the gradual recognition of the statehood of Somaliland and international efforts to mediate outstanding bilateral issues between Hargeisa and Mogadishu.

The Sahel region also presents many challenges for coherent US policies in Africa. The destabilisation of a whole swath of territory from Libya’s borders into Chad poses formidable obstacles to policymakers. The problems are compounded by the multiplicity of states, Islamist groups, regional institutions, and international actors that prevent consistent approaches. The core Sahelian countries — Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger — have been ravaged by several extremist forces, such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which gained prominence after the collapse of the Libyan government of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, and the onset of the Malian civil war in 2012.

In response to these security threats, these countries formed a platform in 2014 called the Group of Five for the Sahel (G5 Sahel). Although the US and other external players have assisted the G5 Sahel in counterterrorism initiatives, recent reports suggest that these efforts have not improved security in the region. Instead, things are only getting worse, particularly for civilians.

Similarly, the combination of food insecurity, conflicts, terrorism, displacement and climate change have spurred countires in the Lake Chad Basin – Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria – to coalesce into a regional joint multinational task force to launch military strikes against Boko Haram and other insurgents. These countries have also been recipients of security assistance from the US and western countries. But like the Horn, critics have charged that military assistance to largely undemocratic regimes in Benin, Chad and Cameroon has undermined the insurgency campaigns and emboldened terrorist groups. Chad, the star player in both the G5 Sahel and the Lake Chad Initiative, has been embroiled in a governance crisis since its long standing dictator, Idriss Deby, was killed in April 2021 by rebel forces, enabling his son to unconstitutionally take power. Should Chad descend into more violence, it will be an apt lesson on the dangers of the US aligning itself with countries with dubious governance credentials.

In a stark acknowledgement of the failure of regional counterterrorism efforts in the Sahel, Nigeria’s President Mohammed Buhari invited the US on 27 April, 2021 to consider moving Africom to Africa to better support the fight against rising insecurity. This invitation was a radical departure from the previous position articulated by major African countries to oppose US military bases on African soil. Although most Nigerian commentators described the invitation as a precursor to US “recolonisation” of Africa, it represents a remarkable shift toward transparency and honesty in African engagements with the US military. After all, African governments have routinely accepted US security assistance, and Africom has been visibly active in most regions of the continent; the relocation of Africom to the continent potentially gives African countries some measure of control on what it does and how it operates.

At national levels, a new narrative on US-Africa security relations ought to be anchored on transparency in defence spending. While critical due to the growing security needs, defence spending in the majority of African countries has always been controversial because governments often do not provide accurate and precise information about it. Neither do they adequately explain the trade-offs between security and social investment. In the absence of this information, ordinary citizens tend to be sceptical about defence spending, deriding it as wasteful. To get around this problem, African governments need to sensitise their publics on the significance of defence spending, including how much security assistance they obtain from external sources. Open budgetary governance around defence and security allocations would do three things. First, strengthen civilian, particularly legislative, oversight over the military, an essential component of democratisation and stable civil-military relations. Second, enhancing accountability in defence spending helps citizens appreciate why governments need to invest in well-resourced security forces, ultimately making them core stakeholders in defence and security. Third, it would enable the US to make better choices in the allocation of security assistance to African countries. By this logic, countries making steady progress towards democracy and governance would deserve more security assistance than the laggards.