Nigeria: Africa’s richest man bets on the continent’s prospects

Playing politics has helped Aliko Dangote build his business empire

At age 57, Aliko Dangote is Africa’s richest man, and by quite some margin. Forbes estimates his net worth to be $20.8 billion; the wealth of his nearest competitor, South Africa’s Johann Rupert, is valued at $7.9 billion. Mr Dangote is known as a soft- ly-spoken workaholic, with all the trappings of wealth, including the luxury yacht and the private plane.

But it is not the size of his fortune that matters. More important is how he made it—not through resource extraction or milking state coffers, but by gambling repeated- ly on the future of both Nigeria and Africa. The risk has paid off, spectacularly, making Mr Dangote a living embodiment of the “Africa rising” narrative, and his company one of the key drivers of Africa’s economic development.

It all started in 1977, when 21-year-old Mr Dangote—fresh from a business de- gree from Egypt’s Al-Azhar University—begged his uncle for a 500,000 Nigerian naira loan (then worth about $325,000). Mr Dangote’s family were wealthy Muslims from northern Nigeria. His father Mohammed was a prosperous commodities trader, but the real money was made by his maternal grandfather, Alhaji Sanusi Dantata, whose groundnut empire made him the wealthiest man in west Africa. Mr Dantata’s son, Abdulkadir, was the uncle who gave Mr Dangote his first start in business—and, before his death in 2012, was also one of the richest men in Nigeria.

Mr Dangote could have gone into business with either his father or his uncle. Instead, he chose to strike out on his own, using the loan to start a general trading company, importing bulk commodities like sugar and rice. Business was good, but he soon discovered a gap in the market: why was Nigeria importing sugar when it could be producing its own? Why was the country bringing in expensive cement when it sits atop one of the world’s largest lime deposits?

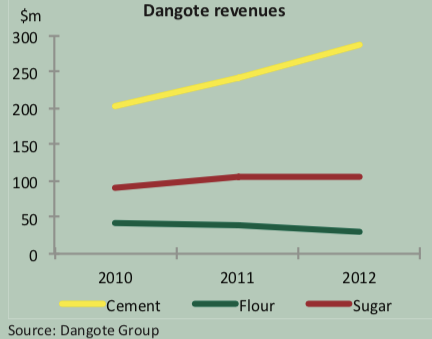

The answers to these questions—conflict, corruption, incapacity, uncertainty— lie at the heart of Africa’s decades of stunted development. Mr Dangote, however, was undeterred and resolved to move into manufacturing: first salt, then flour and sugar and then cement, which turned out to be the really big money-spinner.

Mr Dangote’s philosophy is known as “backward integration”. Backward inte- gration is when a company acquires its own raw materials or component suppliers. In Nigeria it means import substitution: it encourages Nigerians to make their own ma- terials instead of using foreign supplies and equipment. This stimulates the economy through more employment and investment, keeping Nigerian money in Nigeria.

Thanks largely to Mr Dangote’s success in the cement sector, backward integration has become official government policy, included as a central plank of President Goodluck Jonathan’s Nigeria Industrial Revolution Plan, which was introduced last February.

At the same time, Mr Dangote is politically astute: he has carefully navigated his way through changing governments and regulations, emerging unscathed and with bigger profits, every time. His political connections proved crucial to the scale of his suc- cess, especially his relationship with former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo. Mr Dangote funded Mr Obasanjo’s 1999 and 2003 election campaigns and Mr Obasanjo returned the favour by introducing restrictions on imported cement in 2001, among other items.

“Dangote is counted among President Obasanjo’s inner circle of business advi- sors,” observed Brian Browne, former US consul-general in Lagos, in a 2007 diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks in 2010. “It is no coincidence that many products on Nige- ria’s import prohibition lists are items in which Dangote has major interests.” Besides cement, sugar and rice receive protection from external competition—and the Dangote business has significant interests in both.

In fact, the Dangote Group has substantial shares in just about every major sector of the Nigerian economy. It makes salt, sugar, rice, pasta, flour and fruit juices; it supplies steel, cement and packaging; it buys and sells property, and holds a 3G telecommunications licence; it manages ports; it operates a 5,000-truck-strong haulage fleet. If you can think of it, the Dangote Group is probably doing it, and making plenty of money in the process.

Last year, the Dangote Group claimed that its annual turnover was in excess of $3 billion, or about 30% of the Nigerian stock exchange. It is, by some distance, Nigeria’s biggest company, and ambitious expansion plans mean that it is only going to get bigger. “Dangote is going to go haywire now,” observed Lyal White, director of the Johannesburg-based Centre for Dynamic Markets, an economics think-tank. The Dangote Group has almost no debt, giving it the perfect foundation for the planned expansion, Mr White added.

Another crucial factor in the Dangote Group’s success has been the steady growth of the Nigerian economy, which has expanded an average 7% every year for the last decade. This growth is often dismissed as a resource bubble, fuelled by Nige- ria’s vast oil reserves. But driving these impressive figures are other factors: increased agricultural output, significant enlargement of the manufacturing sector (7.7% in 2013 according to the World Bank) and booming retail and construction sectors. This growth has benefited Mr Dangote’s businesses.

“[Mr Dangote] is intimately entwined with the rise of Nigeria,” Mr White said. “If Nigeria does well, so does he.” Given the size of the Dangote Group and the sheer breadth of its operations, the reverse is just as true: Nigeria needs Mr Dangote to keep doing well, to keep creating jobs and to keep re-investing in the country.

In this, Mr Dangote is something of an anomaly. In bestowing him with its 2013 Man of the Year Award, Nigeria’s Daily Independent noted in January 2013 that Mr Dangote is “one Nigerian who makes his money in Nigeria and also spends it in Nigeria for the benefit of the country’s economy; unlike several other Nigerians who spend their wealth buying houses and other choice properties abroad, or stacking them into foreign banks to the detriment of the growth of their own country’s economy, Dangote is always at home with his business.”

Indeed, Mr Dangote—who appears just as comfortable in a loose traditional kaftan as he is in a business suit—spends at least half his time in Nigeria. He divides the rest between London, where he is prepping

to list Dangote Group on the London Stock Exchange, and other countries, mostly in Africa but also abroad, where he is looking for or exploiting new opportunities. Home is a mansion on Lagos’s Victoria Island, which he shares with the younger of his 15 children from four different marriages. Mr Dangote is currently unmarried and still smarting from the public rejection of his advances by the daughter of the late president, Umaru Yar’Adua, according to press reports.

The list of new projects, for which Dangote plans to invest around $16 billion, is enormous. Within Africa, five new cement plants will come online this year, in Gabon, Republic of Congo, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia. (In South Africa, the Dangote Group’s acquisition of 64% of local company Sephaku Cement is the largest single foreign direct investment in South Africa by an African company.) More are planned in Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Senegal and Sierra Leone. These will complement the export terminals already in place in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Dangote Sugar, meanwhile, will start exporting to Liberia, Mauritania and Senegal.

Outside of Africa, Mr Dangote has plans to work in Myanmar and Iraq, and has obtained all-important limestone mining rights in Indonesia and Nepal. He is also looking across the Atlantic Ocean. In January, Devakumar Edwin, Dangote Cement CEO, announced that the company had signed a joint venture agreement with an un- disclosed company to tackle the South American market.

Nigeria has not been overlooked. On the home front, Mr Dangote is planning to invest in a natural gas power plant to boost the country’s power supply, and to ap- ply his “backward integration” to rice. “We think Nigeria can be self-sufficient in rice in the next three to four years,” Mr Dangote said in a December 2013 interview with Bloomberg. His biggest project, however, is a $9 billion investment in a huge new oil refinery in the Olokola Free Trade Zone, located 45km east of Lagos, which could turn Nigeria from a net importer of petrol (absurd for Africa’s largest oil producer) into a net exporter. Accompanying this will be Africa’s largest fertiliser plant and a polypropylene plant, to take advantage of the chemical by-products of the refining process.

So far, Mr Dangote’s rapid expansion has been relatively smooth. Aware that he brings jobs and deep pockets with him, African governments in particular have wel- comed his attention. Presidents clear time in their schedules to meet him. Mr Dangote knows the importance of these interactions. “He understands the value of commercial diplomacy more than anyone I’ve ever seen,” Mr White said.

Nonetheless, it has not all been plain sailing. In the Senegalese town of Pout, 40km west of Dakar, the shiny new Dangote Cement plant lies dormant as the group battles legal action from competitors who say the new plant was built in violation of safety standards and without a proper environmental impact assessment. This, the competitors allege, will allow Dangote to undercut the market. And during construction, a court found that the same plant encroached on a sacred forest owned by the descendants of a famous Sufi mystic. Construction could only continue once Dangote had appeased the family with a $12.6m pay-off, AFP reported in March 2014.

Other, potentially more serious obstacles may block Mr Dangote’s path to con- tinental—and, he hopes, global—dominance. One is simply that the company is ex- panding too far and too fast. Managing this growth effectively is a major challenge. Can the group recruit enough skilled managers, especially as it has previously preferred to recruit from Nigeria, where high-level skills are in short supply? Can it find enough re- liable power, particularly in other African countries, to run its energy-intensive plants? Can it set up continent-wide supply chains that successfully negotiate the hazards (and associated costs) of border crossings and changing regulations?

Another barrier is the man himself. Mr Dangote is a notorious micro-manager, involved in the smallest decisions. This quality, coupled with an exceptionally strong work ethic, has underpinned his fortune. As the company gets bigger, however, Mr Dangote simply cannot maintain the same level of control. How he devolves responsibility, and whether he is able to properly corporatise the company, will determine its future, Mr White said.

A third potential hurdle is Mr Dangote’s close political connections, which he has repeatedly parlayed to his advantage. Mr Dangote is very close with Nigeria’s ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP), having funded the election campaigns of three presi- dents: Obasanjo, Yar’Adua and Jonathan.

Going into the 2015 elections, however, the PDP is facing an unprecedented threat from a new opposition coalition, the All Progressive Congress (APC). Dozens of high-profile PDP members, including governors, parliamentarians and even former vice-president Atiku Abubakar, have defected to the new party. The APC is likely to provide the PDP with its toughest ever electoral challenge. A chance exists, albeit a slight one, that the APC may even triumph.

If it does, where does this leave Dangote? Will a new government undo some of

the legal protection his business enjoys? Perhaps not. Given the sheer size of the Dangote Group’s contribution to the Nigerian economy, most politicians would probably conclude that they need Mr Dangote more than he needs them. Still, it is a concern for a company that is so invested in the prevailing political currents.

For Mr Dangote, however, these are but minor obstacles. He knows that with a proven track record in Nigeria, a huge cash surplus and almost no debt, his company is ideally positioned to become a global player. This is particularly true in the cement sector, which is by far the biggest part of the business.

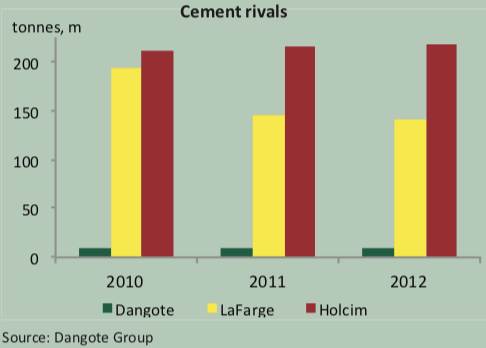

In terms of market capitalisation, Dangote Cement ($24.5 billion) is behind only cement behemoth Holcim, despite producing only a tenth of the output generated by the Swiss-based building materials giant. But Holcim is drowning in debt, forcing it into an uneasy merger with LaFarge, another struggling cement giant based in France. Should regulators approve the deal, Holcim-LaFarge would be the world’s largest cement producer by some distance. The problem with producing so much cement, how- ever, is finding customers to buy it; and the future of the merged company is hugely dependent on finding a foothold in developing economies, particularly in Africa.

Unfortunately for Holcim-LaFarge, Dangote is already well on his way to sewing up the continent. The investments detailed above give the company a huge head start in what is certain to be an exceptionally lucrative race to provide, quite literally, the building blocks for African development.

Every house, every office, every road, every dam and every power station—everything that Africa must

and will build over the coming decades to address the infrastructure deficit—will require cement and tonnes of it. Supplying much of this demand will turn the Dangote Group into one of the world’s biggest companies. “We are targeted now to be one of the 100, in terms of ranking, global companies by 2017,” Mr Dangote said in an interview with Bloomberg last January.

Aliko Dangote made his fortune by gambling on Nigeria’s success when others would not dare. The risk paid off, both for him and Nigeria. Now he is looking to make another wager, this time with even bigger stakes. For it to stick, he needs Africa to keep developing. For Africa to keep expanding, it needs people like Mr Dangote to keep sinking big money into the continent—and then re-investing the profits. So far, it is less of a long shot and more like a sure bet.