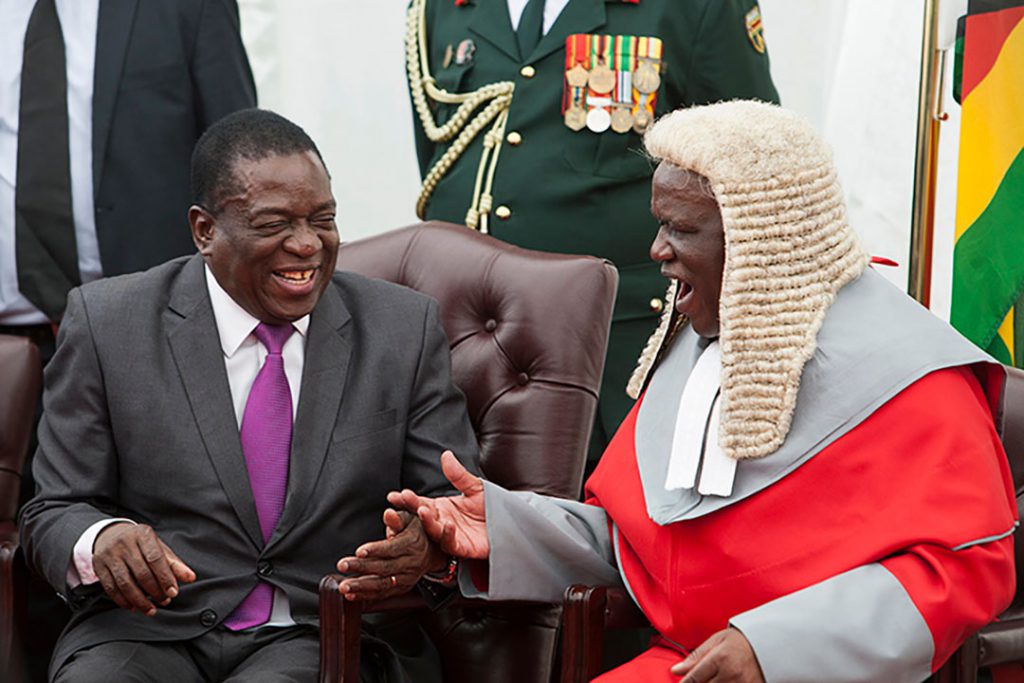

Emmerson Mnangagwa (left) and Chief Justice Luke Malaba at the new Zimbabwe president’s swearing in ceremony in Harare on 28 December, 2017 PHOTO Wilfred Kajase/AFP

Zimbabwe’s new president has vowed to entrench constitutionalism and uphold the rule of law, but recent events suggest otherwise

The attempt to reverse decades of Zimbabwe’s economic ruin after Robert Mugabe’s fall in November 2017 was always going to be the most urgent priority for President Emmerson Mnangagwa, the man

who took over after Mugabe.

The economic collapse left behind by Mugabe after 37 years in power was staggering. The country was cut off from the rest of the world by nearly two decades of sanctions, hamstrung by severe foreign currency shortages; and Zimbabwe also had external debts of over $7 billion owed to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Excessive government spending, company closures and job losses also rendered about 90% of the population unemployed and made the task ahead for the 76-year-old Mnangagwa unenviable. His inheritance was not going to be “the jewel of Africa”– as former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere referred to Zimbabwe in the early 80s – but only ashes. Still, Mnangagwa pledged to turn around the country’s economic fortunes and vowed to citizens and to the international community that under him “Zimbabwe is open for business”.

But underneath the ruins of the economic collapse was the question of constitutionalism, which posed a litmus test of Mnangagwa’s sincerity to chart the country on a new course. Under Mugabe, Zimbabwe gained global notoriety for deviating from constitutionalism, a period characterised by disregard for court rulings, arbitrary detentions and arrests, the use of repressive laws against opponents and heavy-handed police responses in enforcing public law and order. This was despite the adoption of a new constitution in May 2013, widely viewed by constitutional experts as a guarantee for the constitutional freedoms of citizens.

Former President Robert Mugabe talks to the press the day before the national elections. He announced that he wouldn’t be voting for Zanu PF.

Casting a long shadow over Mnangagwa’s claims to reform was how he rose to power, via a military coup which ousted Mugabe, against which his claims that constitutionalism would be the guiding light for his administration sounded hollow.Ibbo Mandaza and Tony Reeler, co-conveners of the Platform for Concerned Citizens, said under Mnangagwa, Zimbabwe had in fact “drifted into deeper and more dangerous waters”, with the coup and attendant constitutional crisis. “Whether we call this a military assisted transition, the enforced resignation of the president, a “soft coup”, or even the “non-coup” coup, the military came onto the streets in defiance of the Constitution,” Mandaza said in a note. “We might all celebrate the removal of Mugabe, but the manner of his removal violated the Constitution.

“The internecine political party fights, the paralysis in policymaking, the absence of active governance, the spectre of increased violent repression, and, above all, the serious disappearance of livelihoods and a safety net for citizens are driving the country into further chaos. Above all of this is a total absence of any real vision for the future as well as nationally minded leadership, and this is not cured through a factional coup.”

Presiding over a graduation ceremony held at the University of Zimbabwe in October last year, Mnangagwa, a former justice minister under Mugabe, vowed to follow the Constitution. At the time, he was just two months into his presidency, after the Constitutional Court declared him the winner of the disputed election.

“Drawing from the spirit and values that inspired the fight for our country’s liberation, my government is committed to entrench constitutionalism, rule of law, democratic tenets, principles and values,” Mnangagwa said at the time.

But Derek Matyszak, the Harare-based senior researcher for the Institute for Security Studies, says that from the outset Mnangagwa’s early days in power were littered with numerous constitutional violations, and he also had a checkered history when it came to constitutionalism.

“There have been a number of constitutional violations since he came into office, such as the appointment of ministers, and one wonders what sort of advice he has been getting from his advisors in the government,” Matyszak said in a telephone interview.

Far from being a doyen of constitutionalism, Matyszak highlights how Mnangagwa was the key driver of constitutional amendments that led to the appointment of the chief justice, deputy chief justice and judge president directly by the president – opening up the judiciary to interference by the executive.

“Mnangagwa doesn’t have a good record of democracy, and as the justice minister he was the driving force behind constitutional amendments which brought the judiciary under the executive,” Matyszak said. “It was a massive step backwards on the gains made on the 2013 Constitution. Mnangagwa is also responsible for undermining the independence of the prosecutor- general, through the removal of private prosecutions.”

The World Justice Project’s report Rule of Law Index 2017-2018 reflects Zimbabwe’s rock-bottom status; the report ranked Zimbabwe 108 out of 113 countries around the world. Among 18 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Zimbabwe was ranked number 17 by the report. The Index measures eight factors and these include: constraints on government powers; absence of corruption; open government; fundamental rights, order and security; regulatory enforcement; civil justice and criminal justice.

The army in Harare during military crackdowns, 1 August 2018. PHOTO Graeme Williams

Even after Mnangagwa’s disputed election win, with which he secured a five-year term mandate, political observers said little had changed under his watch, and had even got worse. The military has adopted an increasingly visible role in civilian affairs and was at the centre of two events, in August last year and in January, which involved a crackdown on citizens.

The military quelled demonstrators protesting the release of election results on 1 August, 2018 in Harare’s city centre. At least six people died and 35 were injured, according to the findings of a commission of inquiry headed by former South African President Kgalema Motlanthe and which were released in December last year. It remains unclear from the commission’s own findings who deployed the soldiers onto the streets of Harare, although the Constitution says that only the president may do so.

At the same time as the political heat over delays in the release of the presidential election results increased, opposition leader Tendai Biti fled for his life and sought asylum in Zambia. He was deported by Zambian authorities and handed over to their counterparts in Zimbabwe.

Mnangagwa, in a message on his official micro-blogging site on Twitter, said that he “intervened”, resulting in the courts releasing Biti on bail. This incident offered a glimpse into how, behind the scenes, the judiciary panders to the whims of the executive.

“The rule of law issues that have been in play and the allegations of subversion are of critical importance in terms of the challenge that Mnangagwa faces in showing the world that there is due process, that there is rule of law without fear or favour,” said the southern Africa consultant at the International Crisis Group, Piers Pigou, in an interview.

In January this year, the military was also deployed to crack down on protestors angry at a 150% increase in the price of fuel. With this heavy-handed response, the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum said, the army killed 12 people, injured 78 people, who suffered gunshot wounds, and there were 844 various human rights violated. Police said 1,000 people were arrested across Harare, Bulawayo and the Midlands provinces.

Mnangagwa was out of the country, on a five-nation tour of eastern Europe, at the time of the protests. The Constitution says an acting president [Constantino Chiwenga was left in charge] cannot deploy the army in the absence of the president and to do so must have a full cabinet endorsement. Again, it is unclear if the Constitution was followed in the deployment of the military.

Douglas Mwonzora, the secretary-general of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) and one of the key writers of Zimbabwe’s Constitution, told Africa in Fact that he had watched the brutal assault on the Constitution under Mnangagwa.

“There has been a breakdown in the rule of law, and the Constitution and the Bill of Rights as they relate to human rights have effectively been suspended. There have been arbitrary arrests and inhumane and degrading treatment of people,” he said.

In January, hundreds of lawyers dressed in their black gowns marched to the Constitutional Court in Harare’s city centre, echoing Mwonzora’s assessments, and they called for the immediate restoration of the rule of law and order in the country.

The march was organised by the Law Society of Zimbabwe, the largest body in the country bringing together legal practitioners. The organisation said that fast-track trials, the routine denial of bail and dismissal of applications, and the blatant disregard of the constitutional provisions relating to the right to a fair trial were “causing alarm in the profession”.

Given this state of affairs, Mwonzora said the only way out was for the international community to intervene. “The current situation needs the intervention of the international community; we are dealing with a rogue regime. There is no respect of the right to life, of our lives,” he said.

So far, there has been widespread condemnation of the military’s brutality, including by the UK government, which was initially supportive of Mnangagwa. But beyond the statements and public comments, other competing geo- political events will likely overshadow these, meaning the unfolding political crisis in Zimbabwe will take a backseat. The UK government, the Mnangagwa administration’s biggest ally on the international stage, has to contend with Brexit, while the region’s largest economy, South Africa, has elections in the second quarter of this year.

Zimbabwe’s citizens have been here before, finding that they are on their own. “We want there to be respect for the Constitution, human rights, and that trials be done in a fair manner,” leading human rights lawyer Beatrice Mtetwa said.