West Africa’s powerhouse – bedevilled by infrastructural decay, corruption, inefficiency and lack of capacity

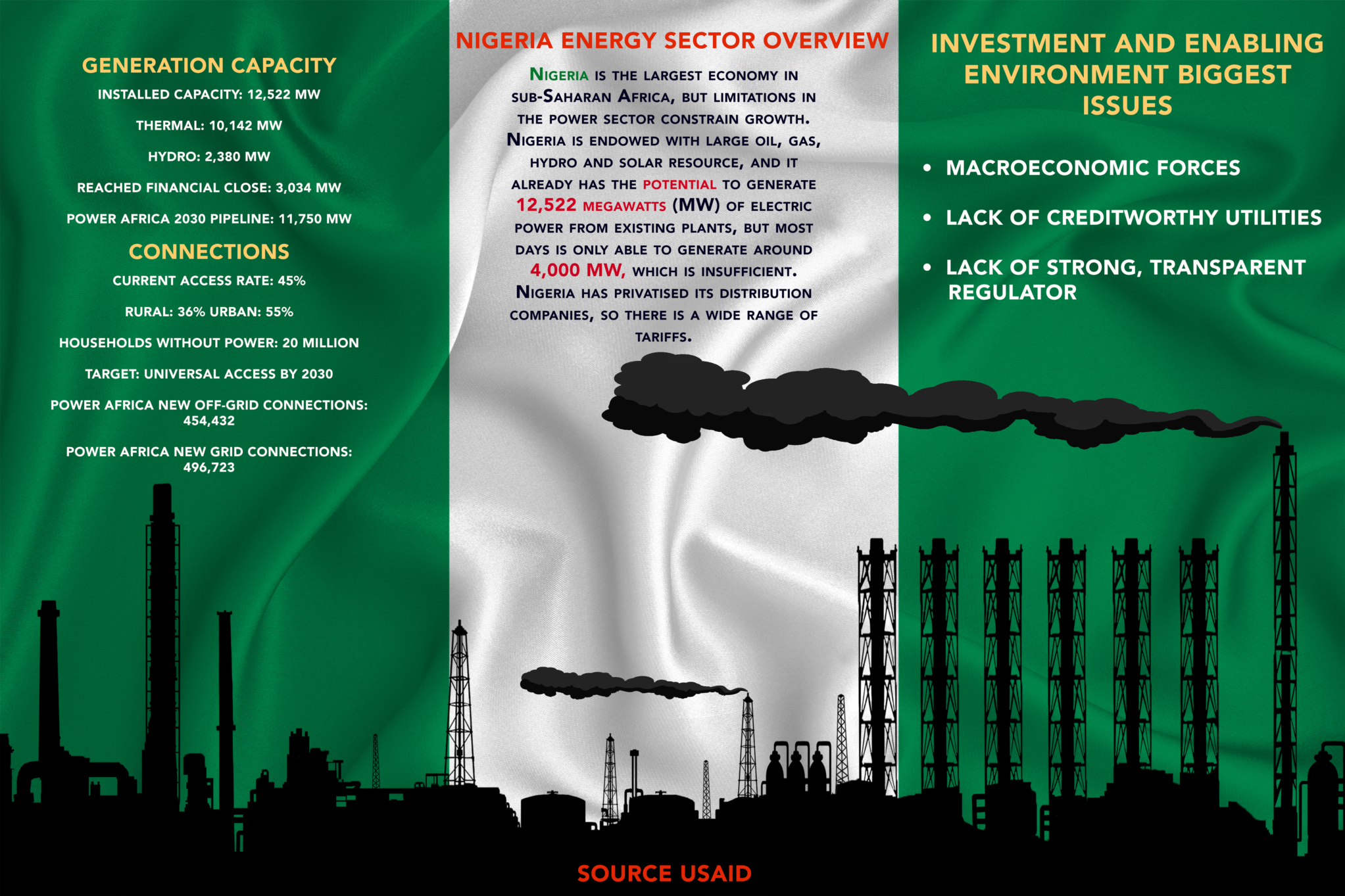

Nigeria, sub-Saharan Africa’s largest economy in GDP terms, is one of the most underpowered countries in the world. With a population of nearly 200 million people, years of dysfunction in the power sector means that Nigeria has one of the lowest electricity per capita rates in the world at 150 KW per hour.

In the second-largest economy, South Africa, the per capita consumption is nearly 4,500 KW per hour. About 47% of Nigerians do not have access to grid power, and those who do have access have regular power cuts, according to World Bank (2020).

A combination of infrastructural decay, corruption, inefficiency and a lack of capacity have undermined reform efforts over decades. It is estimated that the Nigerian economy loses $28bn annually due to its power deficit, according to the World Bank.

Vendors sell meat at the Oshodi night market in Lagos, late on June 6, 2015, lighting their stall with a fuel lamp in absence of electricity. Corruption, conflicting interests, mismanagement and labour unrest have for years plagued Nigeria’s power sector. Photo: Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP

Just over 4,000 MW is available for distribution to the national grid, against installed capacity of 13,400 MW. This is due to infrastructure challenges and supply constraints of gas, which provides 80% of power to the grid. The system also suffers from heavy technical and non-technical losses through the chain. By contrast, South Africa, despite having its own power woes, has installed capacity of just over 44,000 MW for a third of the population.

In addition to gas, Nigeria’s power comes from its large hydropower resources and generation from biomass and waste. Renewable energy is starting to attract private sector investment and is benefiting from the government’s roll out of solar power to boost rural electrification efforts. National independent power projects also contribute power to the grid.

But for now, the reality is that most Nigerians still rely on fuel-powered generators, which, collectively, provide eight times more power than the national grid. Nigerians spend an estimated $14bn a year to buy and run them, according to the country’s Rural Electricity Agency (REA) and other experts, money that could be more usefully spent on clean energy options or paying for reliable grid power.

A much-heralded plan to privatise the generation and distribution arms of the national utility has fallen short of expectations that the process would be a silver bullet for Nigeria’s longstanding power woes. Despite the billions spent on the sector, consumers are, in effect, no better off now than they have been for the past few decades.

When the privatisation option was first put on the table in 2005, the national electricity provider, Nigeria Electric Power Authority (NEPA), was suffering from the effects of years of under investment. Its poor service had become the butt of jokes, with many saying the acronym stood for Never Expect Power Again.

In 2005, legislation was put in place to kick-start a privatisation process. NEPA was unbundled into 11 distribution companies (known as Discos) and six generation companies (Gencos), with the government retaining ownership of the transmission infrastructure, responsible for linking the generation companies to the distributors. The authority was renamed the Power Holding Company of Nigeria.

Political elites with international partners and local conglomerates were the main buyers of the assets, which raised about $2.5bn. The process, which was only completed in 2013, was expected to generate significant investment into the sector, end decades of debilitating power shortages and turbo-charge the economy. But the expectations were overly optimistic. Seven years later, the power system is still on life support.

A man holds a placard during a demonstration to protest against the 45 percent raise of electricity prices on February 8, 2016 in Lagos. Photo: Pius Utomi Ekpei

It has become apparent that the privatisation model was flawed, says Precious Akanonu of energy think tank, Energy for Growth. A range of factors, including the non-payment of electricity bills by users (including government institutions) and unrealistically low tariffs, made it impossible for the companies to recover costs and get a return on investment. The bidders, some with no experience of the sector, took a leap of faith, buying decrepit assets and entering a sector with embedded structural problems, including the vulnerability of the gas infrastructure to vandalism and attacks in Nigeria’s oil and gas hub, the Niger Delta.

Akanonu says that the inability to recover costs meant the Gencos and Discos were unable to repay the $780m borrowed from Nigerian banks for the initial purchase, deterring the banks from providing further loans for investment into infrastructure improvements. The Discos have also battled to get consumers to pay, with collection rates only about 30% of debts owing. A culture of non-payment for services has developed over time as people battle with unreliable electricity, which has forced them to spend money on alternatives, mostly costly generators.

Millions of Nigerians do not have meters and are charged on estimated, rather than actual, electricity usage, which they say often bears no relation to how often they get power.

To generate more power requires more investment, but investors are unlikely to invest in a business that is not paid for its services. It is a real conundrum.

The government set up the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Company (NBET) in 2010 as a middleman between the Gencos and Discos in an attempt to get the system working optimally. NBET guaranteed it would buy power from the Gencos and supply the Discos, who would repay it from collections. But it has become a victim of the same culture of non-payment and its resources were quickly depleted. It, too, now owes the privatised companies millions of dollars, further threatening the viability of the system.

The transmission utility, which runs the national grid, is another sticking point. Retained by government in the privatisation process, it suffers from the same bureaucratic inefficiency and under-investment that once plagued the entire system.

So what to do? In 2020, the country’s senate, among others, called for the privatisation process to be reversed, citing a lack of progress under the reform programme. But the calls have met resistance. The Association of Power Generation Companies says the government, which still owns 40% of the privatised assets, should rather address the deep-seated structural issues.

The Director General of the Bureau of Public Enterprises (BPE), Alex Okoh, says re-nationalising the power assets would be a serious mistake. “I think the Discos have become a topical and very emotive issue. We forgot that the electricity sector was almost dead before it was privatised. We must be extremely careful about these key national utilities.” Fixing the problem, he says, requires analysing the entire value chain.

Power expert Sonny Iroche, a former executive with the transmission utility, says reversing the process would be a blow to Nigeria’s reputation as a business destination. “The non-adherence to the sanctity of agreements is not wise. People have committed resources to this process because of the sanctity of agreements.” He says the Covid-19 crisis gives Nigeria an opportunity to reposition the sector and let it realise its potential. “Nigerians aren’t interested in who executes the services. They just want it done. We need to all join hands and look at the problems.” Nigeria, Iroche says, does not exist in a vacuum and it should be able to execute these functions optimally as countries do around the world. “There is no Nigerian way of doing things, there is only the proper way.”

Writing on Nigerian website Stears Business, financial journalist Osato Guobadia says, “The worst-case scenario is that lenders who granted loans to the owners of the Gencos would liquidate their assets and sell the power plants to repay the loans taken. Realistically, given the strategic importance of the power plants, the government is highly unlikely to allow that to happen.”

The best-case scenario is that the discos can improve revenue collection. As the worst offenders are state-owned enterprises, Guobadia suggests the government could take money from their annual budgets and pay it directly to the Discos to clear the debt. But, he says, there is unlikely to be political will for this. There is a third way, he says. “The default scenario is that Nigerians could keep picking up the slack. We could keep granting loans to NBET to pay the Gencos and give newer ones to pay off existing debts. This would potentially evolve into a debt crisis, but at least it would keep our lights on. At least, for now.”

Hopes are now pinned on the Presidential Power Initiative to address the problems. This is a deal with German energy giant Siemens to rehabilitate and expand the grid. It includes upgrading 105 power substations, constructing 70 new ones, distributing up to 35 new transformers as well as installing distribution lines. The target is 25,000 MW of electricity by 2025 – a tall order, given the deep-seated challenges.

The government is also pushing for greater efficiency in the commercial uses of its enormous gas reserves. Olabode Sowunmi, Senior Legislative Aide to the Senate President and founder of the Energy Hub, says the process is being driven by the Gas Master Plan. “This is essentially an aggregation of policies targeting investments and the development of infrastructure to support the investments,” he says.

The government is also fast-tracking the rollout of meters, offering a one-year waiver of import levies on equipment to bring down the costs for consumers. It is also, under pressure from multilateral organisations, moving towards implementing cost-reflective tariffs in the sector and introduced a tariff hike in September 2020 towards this end. Part of the privatisation challenge has been the fact that tariffs have not reflected the real cost of power, which has effectively been subsidised for years.

While the grid is already powered by gas, the government wants to use the resource to build resilience in other parts of the economy. It has directed 9,000 filling stations to reconfigure their infrastructure to use gas, and the Association for Local Distributors of Gas has been established to drive downstream gas distribution to commercial and industrial end users. This has come at a bad time for Nigerians, suffering financial hardships resulting from the pandemic, but many believe it is also a good opportunity for Nigeria to “bite the bullet” and take the tough decisions to make the economy more resilient.