South Africa: read between the lines

A little-known international declaration reveals the government’s reluctance to protect the right to education

© 2012 – 2015 Zapiro (All Rights Reserved)

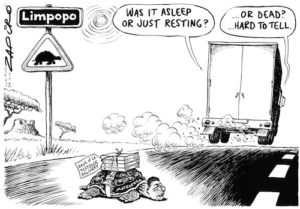

When the infamous textbook delivery case goes back to court later this year, the government may hide behind an obscure declaration, appended to a treaty that is the backbone of international human rights law and the major source of South Africa’s constitution. The schoolbook lawsuit has been central in exposing the government’s violation of the right to basic education. The Department of Basic Education (DBE) appealed a May 2014 North Gauteng High Court ruling prescribing strict deadlines for textbook delivery to schools. The Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) will hear the case at an unscheduled date later this year. The lawsuit began in May 2012, when Section 27, a public interest law centre, and Basic Education for All (BEFA), a community-based organisation in South Africa’s northern Limpopo province, launched an urgent application to force the government to deliver textbooks to schools in the province.

Learners had already gone without the learning materials for the first five months of that school year. A North Gauteng High Court judgement that year stressed that the government was violating the right to basic education because it was not providing textbooks, which it deemed an “essential component” of this right. This litigation “has directed public attention to a component of the difficult conditions under which teachers teach, and learners learn”, wrote Mary Metcalfe, an education professor at Wits University, in an independent report on the progress of court-ordered textbook delivery. During these many public court hearings, the government quietly, and perhaps conveniently, ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural rights (ICESCR), in January 2014. This was more than 20 years after Nelson Mandela signed it in October 1994.

This UN treaty forms the cornerstone of international human rights law. In ratifying this agreement, South Africa joined over 160 states that are legally obliged to work towards the realisation of these rights. Few noticed, however, that the South African government slipped a suspicious declaration into its ratification. The government “will give progressive effect to the right to education…within the framework of its National Education Policy and available resources”, the addendum said. This declaration, qualifying the government’s obligations to provide education, is at odds with the country’s constitution, which guarantees and affords exceptional status to this right. Section 29(1)(a) of South Africa’s constitution states: “Everyone has the right to a basic education.” In the 2011 Juma Masjid case, the constitutional court confirmed that the right to education is “immediately realisable”, and “there is no internal limitation requiring that the right be ‘progressively realised’”.

While the constitution protects other socio-economic rights, such as housing and health care, it does so with less vigour and immediacy. “The state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of each of these rights,” according to the constitution. The landmark Grootboom Constitutional Court judgment in 2000 clarified “progressive realisation” by explaining that “accessibility must be progressively facilitated” and that “hurdles should be examined and, where possible, lowered over time.” In response to the ICESCR’s ratification, several South African non-profit organisations issued a joint statement calling the appended declaration “a deliberate intention by the South African government to misinterpret the right to basic education as enshrined in our constitution”. The other obvious question that arises is: why the two-decade lag?

Ratification should have been fast and easy. South Africa’s constitution is one of just a few in the world that protects socio-economic rights in the same way that civil and political rights are usually safeguarded. The government claims it took 20 years to ratify the convention because the constitution already protected these rights. This explanation is “disingenuous”, said Salim Vally, a professor at the University of Johannesburg’s education department. “Just because the rights are already in the constitution doesn’t mean we mustn’t [ratify the treaty]”, he said. The government also claims it could not identify a single department to oversee the treaty’s implementation because the ICESCR’s scope went beyond the individual mandates of government units, Mr Vally said. This appears to still be the case. A spokesperson for the DBE declined to comment on this story and suggested asking the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO).

Despite repeated attempts to obtain a comment, DIRCO never responded. Without official explanation, one is left to speculate about the reasons for the delay. Maybe the government postponed the ratification because the covenant includes an optional protocol that allows individuals to seek remedy in the UN human rights system when justice at the national level has been denied or does not exist. Or perhaps the government delayed because at least two rights in the treaty are not found in the South African constitution: the right to decent work and the right to an adequate standard of living. The government may be aware that they would have difficulty delivering on those obligations, Mr Vally said. While it is hard to prove intent, the government’s delayed ratification may be tied to a more expedient political motive: the pending textbook litigation. This explanation becomes convincing when one considers the inserted declaration that limits the right to education.

The government undoubtedly knows the difference between “progressively realisable” and “immediately realisable”. By appending the declaration, it is attempting to qualify the right—an action “the constitutional court has expressly rejected in its binding interpretation of the constitution”, said the joint statement from the NGOs. Section 27 and BEFA have filed suit several times because the education department has failed to follow court orders to provide textbooks. In the case under appeal, Judge Neil Tuchten ruled that the department had violated the right to education by failing to provide textbooks to 39 schools by the first day of school. He refused, however, to issue an order to deliver or exercise the court’s power of supervision because “political issues require political solutions” and Parliament was the more appropriate venue. The department of education nevertheless filed a motion to appeal.

Angie Motshekga, South Africa’s basic education minister, said that ensuring every pupil had every textbook by the first day of school amounts to a level of “perfection” that “is not the standard requirement from [government]”, according to various media reports. In November 2014, the North Gauteng High Court granted the department leave to appeal. It is indeed difficult to say definitively what “immediately realisable” means. Yet it seems suspiciously convenient that, while it was fighting this battle in the courts, the government should have quietly ratified the ICESCR and added an unconstitutional declaration limiting the right to education. In theory, a qualification that undermines the constitution—the supreme law of the land—is ultimately meaningless, as no court will apply it. In practice, however, the government may try to use this limitation to escape legal accountability. If it does, it will reveal the education department’s apparent readiness to contravene the constitution and several court judgments. It should raise concerns about its commitment to protect this country’s exceptional right to education.