John Nkengasong, Director of Africa-CDC at a press conference on COVID-19 at AU headquarters, Addis Ababa, March 2020. Photo by Michael Tewelde/AFP

Africa’s fortunes in a post-COVID world will depend on how it navigates the critical questions of vaccine economics – vaccine diplomacy and regional integration. As the continent slowly recovers from the pandemic, it now needs to navigate a trifecta of new challenges – namely, debt, disease and dysfunction. Amid signs of a global economic recovery, continued vaccine inequality and 2020 was a devastating year economically for most of Africa.

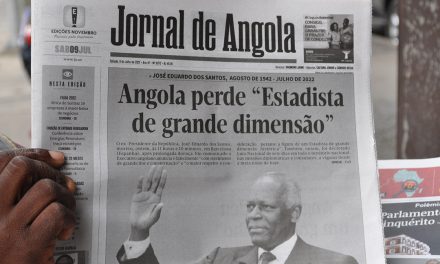

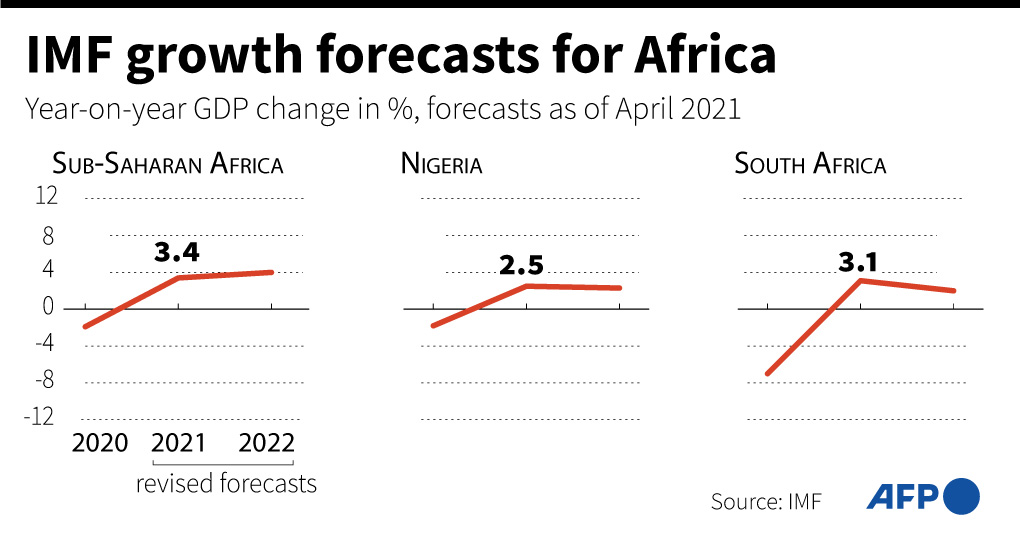

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the continent experienced its first recession in 25 years, reeling from the impact of lower commodity prices, coronavirus shocks and a rapid rise in the cost of funding. Battling with this trilemma, and with already weak balance sheets, many countries struggled to find the fiscal room to fulfil their external obligations.

Zambia, in particular, experienced a perfect storm of negative shocks, which culminated in a default on its Eurobond. This raised fears of contagion and a wider debt problem across the continent. Although debt service costs have subsequently compressed, and economies have been buoyed by rising commodity prices and improving risk sentiment, many countries are still battling debt hangover. This will remain a key area to watch keenly given the opacity around the proposed common framework for debt and the role of private creditors in alleviating these pressures.

Yet despite these ongoing issues, there are some green shoots of a global recovery. The easing of stringent lockdown restrictions has led to a rebound in general economic activity. Commodity prices, so critical to the fortunes of the continent, have recovered from multi-year lows. The IMF All Commodity Index has increased by 26.8% over the past year, copper prices have reached a 10-year high of more than $10,000 a tonne, palladium and iron ore reached all-time highs at one point this year, while most other commodity prices are now above their pre-pandemic prices.

Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari (left) speaks with African Union (AU) Commission Chairman Moussa Faki (right) before the opening session of the Summit on the Financing of African Economies on in Paris on 18 May, 2021 . Photo: Ludovic Marin/AFP

Demand is also being boosted by the United States and China, who are playing a dominant role in driving the strong global growth story. Importantly, recovery has been led by a sharp rebound in consumption and an initial pickup in capital expenditure. Supply side pressures have also eased amid improving conditions, while the global picture is further supported by fiscal and monetary conditions that remain accommodative, thereby boosting confidence.

However, it remains to be seen whether Africa will capitalise on this rosier picture. For the continent, “vaccine economics” will be the key determinant of global growth, with the success or failure of any recovery dependent on how quickly the pandemic can be arrested and, more specifically, how quickly the continent can vaccinate. Failure to do this successfully, will see the continent locked out of the global economy, classified as a laggard continent amid a two-speed global recovery. To this end, vaccine access and vaccine equality have emerged as key priorities, both politically and economically.

With limited financial resources and a lack of bargaining power, the options for Africa to procure vaccines have been limited. Indeed, African countries have been firmly entrenched at the back of the vaccine queue, a situation described as “vaccine apartheid”.To achieve herd immunity African must vaccinate 780 million people (60% of its population). This will amount to 1.5 billion doses at a cost of $10 billion. Yet, as it currently stands, fewer than 2% of global vaccines have been administered on the continent (which accounted for less than 3% of global cases and under 4% of global deaths) – a truly dismal situation.

Dr John Nkengasong of the African Centres for Disease Control (CDC), Africa’s top health official, has lambasted rich countries for purchasing “in excess of their needs”. China has mounted a charm offensive in response, indicating its intention to make its vaccines available as a “public good” in poorer regions of the world, in what is being dubbed a “healthcare silk road”. However, such largesse is not entirely altruistic, with Beijing hoping for a long-term diplomatic return. For their part, if western countries continue along a path of vaccine nationalism, and these vaccines remain either unaffordable or inaccessible, the neglected Global South (and Africa in particular) will be forced to turn to the arms of more benevolent partners.

Indeed, the current circumstances create fertile conditions for a new set of power dynamics, spurred by vaccine diplomacy, to take root in the region. Tellingly, both Russia and China’s style of engagement differs markedly from that of the West, which has been criticised for being both paternalistic and overtly capitalistic.

Moreover, with big pharmaceutical companies courting criticism for prioritising profits over people, this is an obvious area where both China and Russia, with their state-backed approaches, can win hearts and minds of local populaces, curry favour with governments, and use this goodwill to expand their existing trade and investment ties and strategic interests. In this context, “diplomacy”, namely, the speedy and effective rollout of vaccines to countries in need, represents a huge opportunity for global powers to redraw power maps and reshape strategic alliances.

Naturally, the stakes (and the dangers) are high, and the competition is intense to achieve both first-mover advantage and scale. Africa’s emergence as a theatre for competition, along with its overt dependency on the external environment has again re-emphasised the importance of African solutions to African problems.

In this context, the spotlight has increasingly focused on the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), which is being touted as an economic game-changer. As noted by Asmita Parshotam, a trade policy expert, “The AfCFTA comes at a time of great introspection,” she notes. “The pandemic has reinforced the challenges that come with over-reliance on international value chains and highlighted the need for self-sufficiency. The AfCFTA offers an opportunity to reinvigorate industrialisation efforts on the continent and to develop competitive regional value chains that can grow to participate in global markets. Making this a reality is not only about political will; it requires fulfilling and implementing many foundational building blocks necessary for improved trade relations across Africa.”

On a positive note, despite several hurdles and capacity constraints – both humanitarian and financial – live trading under the agreement commenced on 1 January, 2021. The secretariat was launched in 2020 in Accra, with Afrexim Bank providing a $1-billion facility to enable countries to adjust in an orderly manner to sudden significant tariff revenue losses due to the implementation of the agreement. Maintaining momentum in this context was no mean feat. However, it is important to be realistic. The agreement will not be a silver bullet to the continent’s challenges.

Given the complexity of the task at hand and the difficulty in achieving consensus, progress will be incremental at best. The European example, where integration was forged over multiple decades and through various crises is a good bellwether for Africa. Despite numerous challenges, there are several factors that investors simply cannot ignore. The size and scale of the agreement (which will connect 1.3 billion people across 55 countries with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) valued at $3.4 trillion) represents a market bigger than India. This, alongside political momentum not seen in decades, plus the fact that it is an aspirational plan – by Africans for Africans – should enthuse investors, and is particularly important against a backdrop of border closures and hyper nationalism globally.

Moreover, several key themes, which the AfCFTA is trying to achieve – industrialisation, digitisation, and localisation – have been turbocharged because of the pandemic. This should add further impetus to integration efforts. However, there are three key dilemmas Africa’s policymakers must resolve to realise the initiative. The first is harmonising the continent’s heterogeneous economies under one agreement. There are massive infrastructure and industrialisation development gaps among African Union (AU) members.

The second challenge is that forging ahead with AfCFTA will require huge trade-offs from political leaders. They will need to think beyond short-term election cycles and cede sovereignty in policymaking. Aligning continental objectives with a domestic agenda won’t be easy, especially as global populism and nationalism is rising, and protectionist approaches are being advocated. The third dilemma is that for the agreement to succeed, African politicians must accept that the benefits for their countries far outweigh stalling the entire process over pockets of discontent.

This narrative must be driven down to the private sector and electorate. Despite the challenges of debt, disease and dysfunction, and regional developmental gaps, the global reset necessitated by the pandemic – and concurrent shifts in global power dynamics – offer the continent a unique opportunity to chart a new, long-term development path. On an optimistic note, similar to the last financial crisis in 2008/9, when Africa became the darling of the investment world, benefiting from cheap money and buoyant commodity prices, the continent may luck out again with another windfall. This would be a boost for growth and foreign direct investment (FDI) at a time when Africa desperately needs it.

However, governance, both economically and politically, across the continent has regressed since then, and there is no scope to waste this opportunity, given the preponderance of challenges and limited financial power. “African solutions to African problems” will therefore become imperative in the context of heightened nationalism and isolationism globally. The continent’s policymakers must urgently work towards reducing its dependence on the external environment, and accelerate diversification efforts. Regional integration, an obvious economic stimulus, can and must act as a catalyst for growth. Finally, overcoming vaccine inequality will require collective leadership, smart economic diplomacy, and strategic lobbying.

Success or failure in navigating this mixed outlook will largely depend on ideological trade-offs and the political will to make tough choices and concessions.