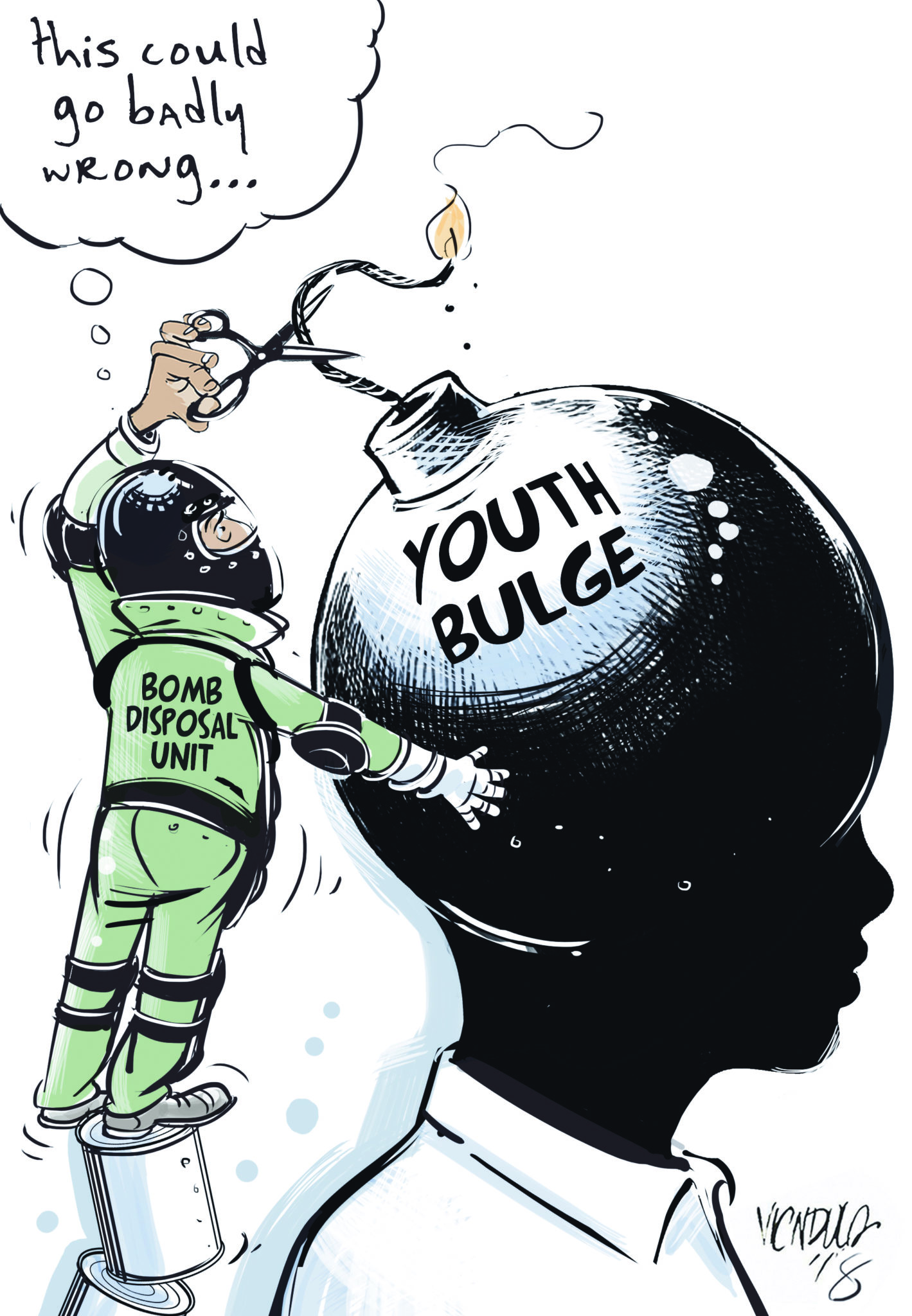

There’s nothing alluring about being called a “bulge”. Positivity rarely inheres within such framing – a bulge is most often a problem. Africa’s population statistics show that young people are the demographic, creative, labour and political majority on the continent, so why are we referred to in this manner? Why have African governments and global institutions taken up the youth bulge discourse with such fervour?

In a recent article for New Internationalist I pushed back against this positioning. Informed by discussions with young people in Kenya and other African countries, I argued that youth on the continent should resist what is ultimately a colonial positioning reinfused with a moral panic about the “ticking time bomb” that African young people are said to represent.

Firstly, it is important to note that the gap between modern economies and African markets is growing. Leaders talk about the challenges posed by the fact that some 60% of Africans are under 30 years old, but they seem unable or unwilling to recognise that this has real implications for their countries. This is despite the constant reminders from scenario planners, technology buffs and consultants.

This is a discourse that, at its very heart, places the fault of this problem firmly with African women, who are not so inadvertently represented as being at fault for bearing too many children. What is more, it builds on Robert Kaplan-esque narratives about the “coming anarchy” since, according to this narrative, unemployed young African men (and it is always men) are seen to portend war, crime and terrorism: are ready, for whatever price, to jeopardise the prevailing “social fabric”.

Such demographic fixations have long circulated about the continent, and certainly they promote Malthusian sentiments, as well as male-centric views, about who the “youth” are in Africa. Furthermore, they enable a logic that draws hard-and-fast correlations between jobless young people and recruitment into violent formations. According to this view, if youth are not provided with jobs they will join gangs or groups such as Al-Shabaab, since such associations offer much-needed monetary remuneration not pegged on “a good CV”. Consequently, these popular narratives imagine that youth will take up arms, destroy lives and property, and so will fail to bring forth a much hoped for generational (neoliberal) “demographic dividend”.

But let’s interrogate these fears. They are the concerns of an older elite, with global bodies helping to institutionalise them through constantly proliferating policy recommendations. Could it be that these anxieties actually stem from the reality that young Africans – from countries as different as Togo, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), among others – are making valid demands for regime change?

Regardless of what ideologies animate them, many of the proposed interventions are aimed at ameliorating the “risks” of this bulge, and discuss the importance of unemployment and training for the 15 – 35 demographic on the continent. To be sure, young people need jobs and education: certainly this age group needs to be able to earn their living. As one of my correspondents from Nairobi put it, young people also need to take care of their families, as well as the myriad of other responsibilities occasioned by the shifting dynamics of kin and economy.

The importance of employment for young people is emphasised by Next Generation Kenya, a report published by the British Council in April 2018, which, to its merit, highlights young people’s concerns about the unavailability of secure and adequately remunerated jobs. One of the young people interviewed is quoted as saying: “getting people to employ us – it’s like a dream that you will probably die without achieving”. Undoubtedly, many from this demographic across the continent share this perspective.

Taken at the surface level, however, one might regard this youth opinion as just a call for “jobs”, while missing that it gestures towards a larger reality: a political economy produced by an older generation that is structurally inaccessible to young people. Theirs is certainly not just a call for employment, but for an economy that serves all. Regrettably, palliative interventions advocating more youth entrepreneurship, for example, do not tackle other impediments such as the cost of living or access to relevant material resources. How can a young person who is told to be an “agripreneur” do so without having any access to fertile land?

Furthermore, policy conversations about the “youth bulge” or the “demographic dividend” place the onus of productivity on youth, yet many questions about the role of previous generations are silenced. It is worth asking: has any current African government rendered a democratic commons that is capable of creating a better future for all citizens? Kenya, today, faces a foreign debt of close to five trillion shillings; this means that, in effect, every Kenyan carries a debt of close to $1,000. Why has this burden been placed on the shoulders of young people? Why are older generations not expected to reflect on the negative dividends they have established as the status quo?

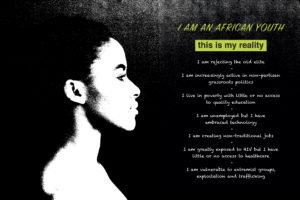

Youth do not only have to deal with the viciousness of an exclusionary economy. In the absence of healthcare and adequate housing, with higher education often inaccessible, and faced with arbitrary police violence, the lives of young people are being shaped by reproducing historical violences. Of course, the extent to which they are affected is often further exacerbated by factors such as gender, location, (dis)ability and religious and ethnic affiliation. But they face these challenges through many ardent, painful, imperfect and determined ways. These situated strategies for survival, however, appear to remain invisible to those who should listen the most.

Faced with this double exclusion, young people are creating alternative spaces for much-needed conversations, often through formal and informal associations that are neither NGOs nor political parties. And even if movements such as LUCHA and Filimbi in the DRC and #FeesMustFall in South Africa are addressing seemingly different issues, they all question the failures of previous generations to establish a fairer system for all.

Similarly, in Mathare, Nairobi’s second-largest poor urban settlement, a collective of young people called the Mathare Green Movement (MGM) come together every Saturday morning to plant trees and reflect on issues such as community and masculinity. Their greening community initiatives are coupled with mural and music making, which speak and act for what they call “Mathare Futurism” – by which they mean a more just, creative and equitable future that they recognise they must bring about through their own socio-ecological efforts.

Mathare, it should be noted, is an area that is synonymous with crime – the apex of all that is considered to be the “risk” of the youth bulge. Their aim is to put right the socio-political, economic and ecological injustices that stricture their neighbourhood, and in so doing to set an example for the nation as a whole. “The world is not prepared for this positive youth movement”, one member told me.

Equally convinced of the power of youth mobilisations to bring about change, in neighbouring Ethiopia members of the National Youth Movement for Freedom and Democracy, also known as Qeerroo Bilisummaa Oromoo, are (re)shaping history. After two years of sustained protests, and the death of many who expressed discontent, they enabled the first Oromo leader of the country, Abiy Ahmed, to be sworn in as prime minister on April 2 this year. Elsewhere, the ongoing protests in Togo to end 50 years of Gnassingbé family rule bear further witness to the resolve of young Africans. Similar developments are emerging in the DRC and South Africa, among other countries.

Meanwhile, against the backdrop of these phenomenal strides being achieved by young people across Africa, older men and women in government offices are still thinking about what to do with this problematic “bulge”. Much of their thinking appears to involve redirecting the blame for the uncertain future they have created on young people, a demographic who are not responsible for the structural challenges that older generations have left them to face.

In my view, the “youth bulge” narrative that informs elder actions represents a set of misplaced anxieties: it boxes young people into normative paths that limit their identities and creativity, and in so doing they delegitimise the alternative spaces and futures being made every day by young people whose resourcefulness is seeing them survive in conditions that are not conducive to their own development. These anxieties are an elite adult blind spot. Whether intentionally or not, they miss important lessons that young people can teach them.

Above all, these multifaceted youth actions are asking the question: how can we create and support authentically indigenous spaces from which to imagine a more just future for ourselves and for others? The answers to this question might well involve approaches and activities that older generations are unprepared for. But these would involve a more positive, creative and dynamic approach than those emerging from the so-called “youth bulge” discourse can ever hope to attain.