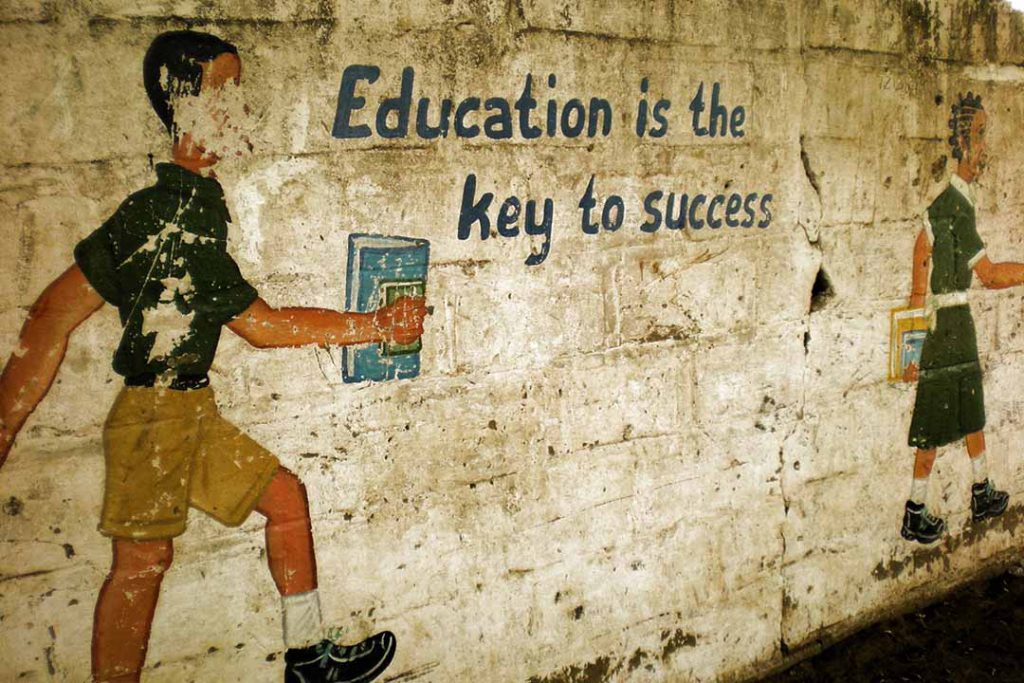

Painting on an outer wall of a school in Senegal.

Africa’s demographic advantages are well documented. Yet, of late, rapid changes and technological advances have divided opinions about these prospects.

For many sceptics, the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) poses a massive threat to the continent’s youth. Machine learning, automation and artificial intelligence raise the prospect of vast job losses and exposes the deficiencies of a workforce that does not currently have the skills to compete globally. Seen this way, the continent’s lack of industrialisation is creating anxiety about what the future holds for Africa’s young, growing population. Governments are ill-prepared, and the “Facebook generation” is impatient.

At the same time, a growing school of thought suggests the exact opposite. Optimists believe that new technologies can foster greater inclusion and innovation by levelling playing fields and providing access to income-generating activities to people who are otherwise excluded from the labour market – and, hence, offer opportunities for sustained “catch-up” growth for many African economies. The concept of “leapfrogging” – where rapid innovation enables countries to skip stages of development – is central to this thesis.

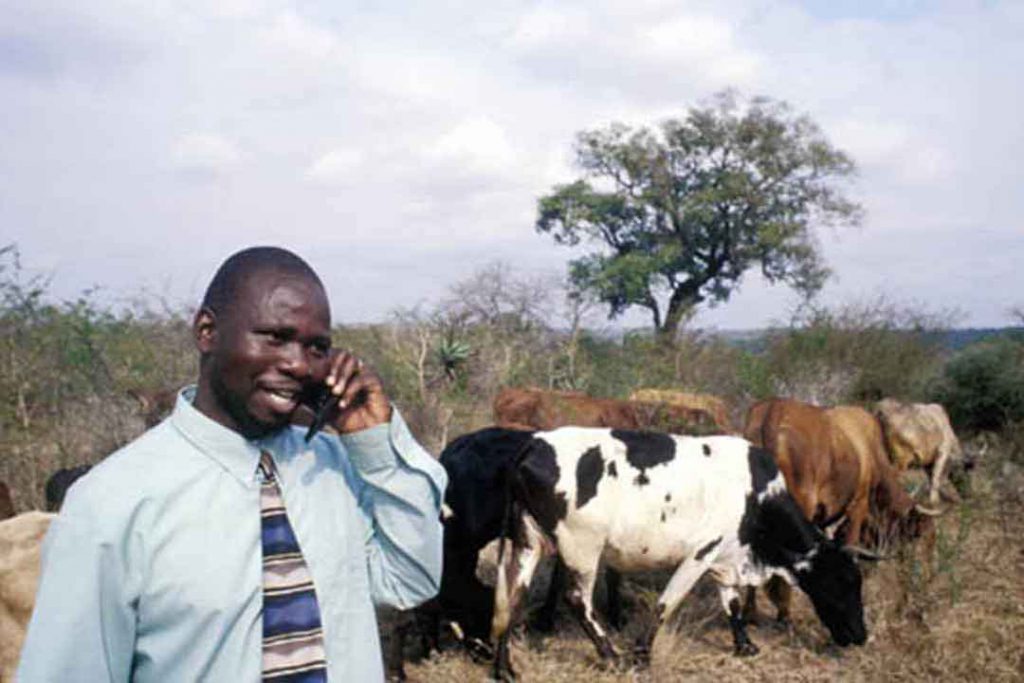

Africa’s experience with mobile phones is often cited as a case in point. Indeed, the mobile revolution enabled many consumers in Africa to leapfrog straight from having zero telephony to mobile telephony. This has enabled telecoms companies to circumvent many of the legacy constraints that fixed lines would have imposed, such as heavy investment in fixed-line phone infrastructure, while reducing obstacles for consumers, such as long lead times for telephone installations.

Mobile telephony has been rapidly adopted and used in many innovative ways in Africa, genuinely transforming some of the continent’s economies and enabling social mobility. A case in point is banking. “Phones now act as banks for millions of Africans who cannot even dream of opening a traditional bank account,” notes Makhtar Diop of the World Bank in an October 2017 opinion piece for China Daily. Another is access to markets: mobile phones now enable small farmers around Africa to assess price information for their crops.

Moreover, as Diop points out, “people can buy solar energy using a phone, get their hearts examined in rural Cameroon using a medical tablet, or get blood delivered by drones in Rwanda.” Given these two wildly different schools of thought, some might ask whether 4IR is a blessing or a curse for Africa’s youth. However, this way of seeing the problem may be too simplistic as Katharina Neureiter of the CDC Commonwealth Development Corporation told Africa in Fact. As she sees it, it’s not an either/or debate.

While technology offers a “transformative power” which “can help African youth (to) level the playing field and overcome a lot of inherent disadvantages such as geography and access to formal education”, she says it can also amplify inequality by leaving people behind in the race for relevant skills, exacerbating unemployment.

What can be said is that digitisation and technology offer opportunities to overcome many traditional barriers to entry, given the nature and scale of the developmental challenges Africa faces, as well as the limitations of many governments in providing necessary services, including healthcare and education, to young populations. In fact, these two areas in particular, both of them critical to Africa’s future prosperity, are seeing rapid development through new technologies.

Babyl Rwanda, for example, a digital healthcare provider, provides medical consultations to anyone with a mobile device by combining artificial intelligence and machine learning with the work of live doctors and nurses. The company offers “a comprehensive, immediate and personalised health service”, according to its website, and says its aim is to offer “an accessible and affordable health service to everyone on earth”. Similarly, using new technology in the area of education has the potential to expand the educational horizons of millions around Africa, where, by 2014, some 30 million children were not even attending primary school.

The key to this is another figure: mobile phone penetration around the continent is around 73%. Edu-tech companies such as Eneza Education have achieved widespread adoption in Kenya by using modern platforms to deliver tailored and original educational content created by Kenyan school teachers to students.

Farmer Kenny Maziya on his cellphone, Mpumalanga, South Africa Photo: Graeme Williams

Despite these positives, though, the new technologies also involve pronounced risks. Globally, they are causing the loss of many low-skilled routine jobs, of which Africa has a disproportionate share. It is estimated that up to 66% of all jobs in developing countries are at risk. Moreover, 4IR is resulting in a “reshoring” of manufacturing back to advanced economies. This creates a conundrum for African countries: how to industrialise while not leaving anyone behind.

The risks of jobless growth or non-inclusive growth are far-reaching. Without jobs or legitimate economic avenues, commentators are concerned that young people might resort to extra-legal means of expressing their grievances by joining rebel groups or terrorist networks. This would mean that the continent could remain trapped in a vicious cycle of violence and poverty, with young people increasingly a major burden on the state. Failure to share the fruits of rapid economic growth with wider society creates the prospect of systemic instability. Given these risks, how can African countries ensure that they end up as victors rather than victims in this situation?

Firstly, it is clear that investing in Africa’s young people will be crucial. “Giving them the skills they need for the future is perhaps one of the smartest strategies for accelerating progress in the region,” says the Brookings Institute in a 2018 Foresight Africa report. Many new jobs will involve complex, non-routine cognitive and interpersonal tasks, and the focus needs to be on creating a workforce that is “fit for purpose”.

Anish Shivdasani, CEO of South African mobile tech recruitment firm Giraffe, agrees. “Upskilling and educating remains one of the most critical imperatives if Africa is to become globally competitive,” he told Africa in Fact. “Priority skills range from basic STEM (science, technology engineering and mathematics) skills and simple digital literacy that the general population needs – for example, how to use a computer, a smartphone and perform Google searches, among other things – to the specific skills that workforces will need to realise the benefits of the fourth industrial revolution – such as coding, data science and social media marketing.” However, he adds that “a prerequisite for this is greater political, social and economic stability without which none of the higher-level development can happen”.

A sense of urgency is needed, he adds. “If Africa does not prepare for the fourth industrial revolution by educating its people and effecting digital transformation of its infrastructure, it may never take advantage of the benefits and thereby fail to become globally competitive, remaining a laggard relative to other regions.”

This view is echoed by others, including Neureiter. Secondly, it is clear that providing quality of infrastructure is the key to providing better and more appropriate education. Fourth industrial revolution technologies can overcome some of these obstacles, but the basic requirements of any functioning economy, such as ports, roads and railways, cannot be bypassed by these new technologies, as The Economist argues in a 2017 special report on technology in Africa. Indeed, the continent still struggles with unstable electricity supplies, comparatively low mobile phone penetration and insufficient road networks, especially in more remote areas.

Technology has undoubted transformative potential and offers potential economic opportunities, but it is important to acknowledge that is not a silver bullet for Africa’s challenges. While innovations like M-Pesa, the world’s leading mobile money service, and Fintech – both of which use software and modern technology to provide financial services – are “sexy” at present, the reality is that Africa cannot afford to neglect primary industries such as agriculture.

The sector currently employs 80% of the continent’s workforce, and it remains particularly important to the continent’s economy. “Apps don’t plough the land,” Parminder Vir, the CEO of the Tony Elumelu Foundation, once famously remarked.

According to Carl Manlan, COO of The Ecobank Foundation, a pan-African development funding institution, current underestimations of the importance of agriculture across Africa are exacerbated by a “rural-urban split” in the ways people think about it. “The urban areas seem to have caught the (4IR) wave, but what really matters to the African economy is agriculture,” he told Africa in Fact. “There’s no point in chasing after a bullet train for a hoe and subsistence agriculture.”

Africa’s significant opportunities lie in value chains in the areas of natural resources and agriculture, Manlan argues. African countries would be well advised to use 4IR technologies to generate more employment by improving the efficiency of food production and consumption in the continent. Used effectively and intelligently, such technologies could indeed help to generate greater access to economic opportunities for many people.

They could also help to foster a healthier and better-educated work force, which would in its turn provide an important stimulus for industrial production. Harnessed effectively and complemented with the appropriate educational and institutional structures and reforms, such measures could further help to generate productivity booms in many African countries.

The effects of successful policies in all of these areas would be mutually reinforcing, helping to create a cycle of sustained growth, reducing inequality and creating greater inclusion. Yet some critics say that this debate misses the point. For all the talk of machine learning, artificial intelligence and robotic automation and the like, many countries in Africa are still struggling to name streets, fix potholes, provide functioning wi-fi and solve basic sanitation needs, among many other problems.

The concern is that the continent’s ability to provide basic infrastructure has already fallen behind. Should Africa even be concerned by 4IR? Finding practical and effective answers to this question will be a major challenge to the continent’s policymakers. If the continent is to reap the benefits of its demographics bulge, it must find effective ways to ensure that its young people of working age are able to join the labour market. And that will mean finding a balance between investing in the “economy of the future” and supporting the basic “economy of the now”.