Big cities appear to have a positive impact on food security and access to drinking water, but they also have a reconfiguring effect on families

African cities are on the rise, and the impact of these is only starting to be understood. While many penetrating insights can be obtained from experts in various fields, it is useful to see what some hard data has to add to the emerging picture. Is increasing urbanisation having a positive effect on African well-being?

Fortunately, data related to this question is readily available. The main components – urbanisation and well-being – are monitored extensively, and related data are available from many sources with high reliability and validity. This extensive monitoring means that there is a range of variables related to these issues and if desired complex modelling could be undertaken.

In this piece, however, we have aimed at keeping the method simple and transparent in the interests of providing an analysis that readers can follow, critique and even replicate without requiring an advanced statistical background. To this end, we have used data that is freely and readily available to readers; our analytical procedure is presented as an appendix and our results are presented in a way that will allow readers to interpret and draw their own conclusions. It is hoped that by providing this degree of transparency readers will be encouraged to join the analysis and extend the debate.

The data

For this analysis, we used World Bank data. The variables selected included a range of indicators or proxies of country well-being, as well as a range of indicators of urbanisation. Despite the high number of variables available, we found that data was lacking for many countries. A list of the countries that were included is available in Appendix A.

It must be emphasised that this investigation is only an initial exploration. Outcome data was only available for a relatively small number of African countries (specifically for 19 countries).

Country and city size

A natural question is how to define a city in this context. In this research, we decided to define the city on the basis of number of inhabitants. We chose one million inhabitants as being the minimum that could still be defined as a city. While a smaller number might legitimately have been chosen, we chose one million to ensure that borderline cases were excluded.

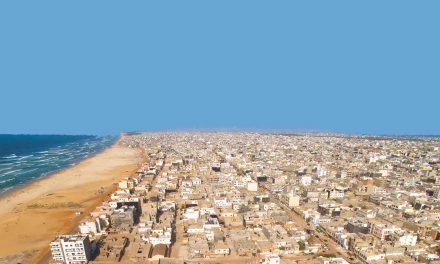

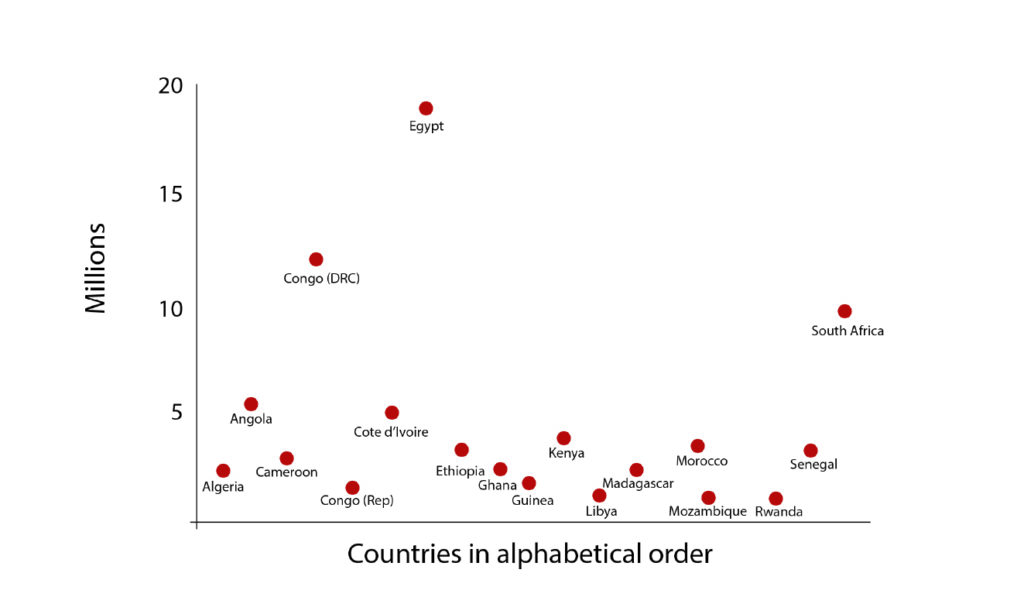

African cities of one million inhabitants or more. Source: World Bank

In addition, the objective of the research was to understand the impact of cities on Africa, which suggests a temporal element. We, therefore, chose to limit our analysis to cities that are experiencing a significant growth rate. We pegged this as 2% of national population.

In addition to these two requirements, we were limited by the availability of data. Many countries were found to lack some of the key indicators. Therefore, these had to be excluded. In the end, the two criteria of city size and growth rate, and the availability of data, resulted in a sample of 20 countries.

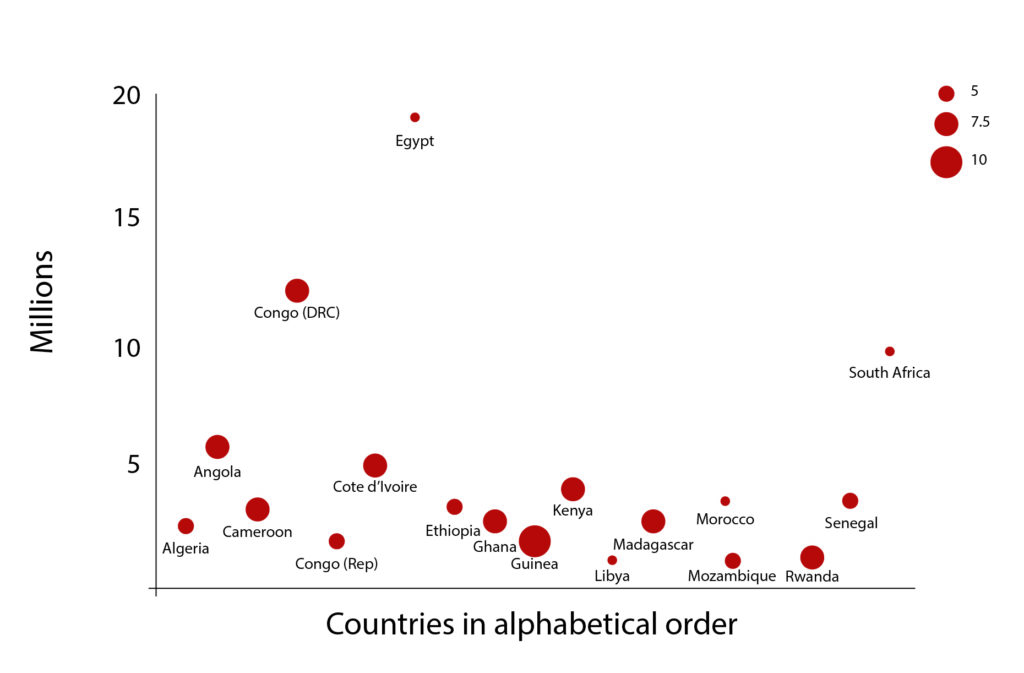

African cities by growth rate percentage. Source: World Bank

Urbanisation variables

For the remaining countries, we compiled a range of variables representing country well-being. Despite being limited in our choice by data availability, we managed to cover a range of key themes, including health, water, ICT access, employment, GDP, gender equality, and education. In the choice of variables, we were somewhat constrained by those which were available across a number of African countries. The predictor variables included the proportion of the country population living in urban agglomerations of over one million people.

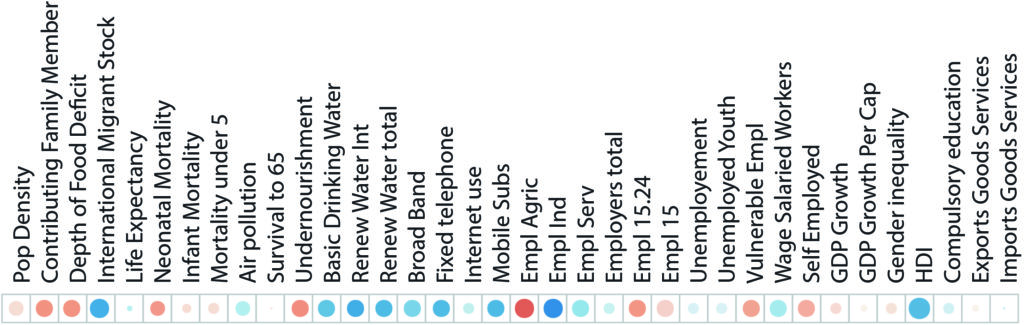

Figure 1 presents the urbanisation variables correlated with the proportion of the population living in urban agglomerations of over one million. Reading across from the urbanisation variables on the left, any darker red or blue indicates a possible relationship between urbanisation and the corresponding well-being variable.

Figure 1: Population agglomeration one million

Figure 1 shows a number of strong correlations, both negative and positive. These can be grouped into four or five categories: employment, ICTs, water, primary health, and food.

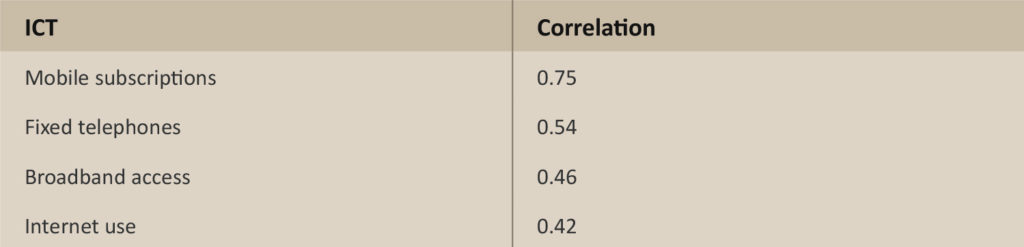

Information and communication technologies (ICTs)

ICTs have made a rapid advance in the African context over the past two decades. The impact of these is still being explored, with suggestions that ICTs could allow Africa to “leapfrog” several stages of development. The inclusion of ICTs in the analysis is therefore of immediate interest.

When compared to the proportion of people living in big cities, we found some strong positive correlations in this group of variables. The strongest correlation was with mobile phone subscriptions; living in a big city has a strong impact on people obtaining subscriptions. The data does not necessarily mean that more mobile phones are being used; it is possible that people in rural areas use mobile phones as readily – only that they use a pay-as-you-go system rather than subscriptions. Fixed-telephone use is also strongly correlated with living in a large city, although here it is evident that more phones are being used.

Living in large cities is also correlated with higher internet usage, and especially high-speed broadband. This is unsurprising; cities typically have a good internet infrastructure. If ICT usage is indeed a catalyst of developmental surge, then this is an area in which cities are a positive phenomenon.

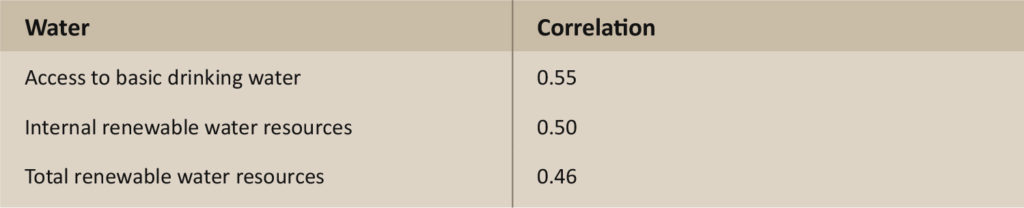

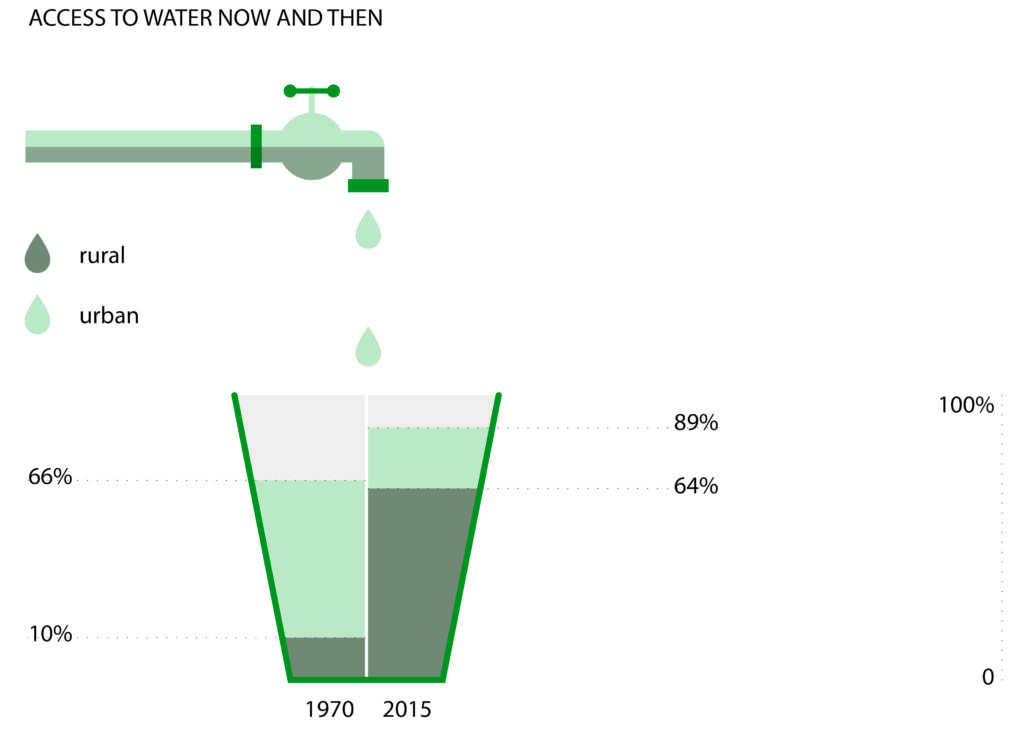

Water

Water has always been a challenge in the African context; forecasts suggest that Africa will be among the hardest hit by climate change. We felt it important, therefore, to estimate the impact of cities on water supplies in African countries.

While it might be expected that larger cities place a drain on water, our analysis indicated otherwise. Larger cities seem to be related to more positive water scenarios than smaller cities. This is understandable, perhaps in that our variable measured the number of people living in large cities as a proportion of the country population. This, therefore, should be interpreted as for any given population; the greater proportion that live in cities, the more favourable the water conditions. In other words, unit for unit, the big city seems to be better able to use water sustainably than rural areas.

More specifically, big cities had a positive impact on the availability of basic drinking water. This was specifically in relation to basic drinking water. When considered in relation to this variable, it is reasonable to assume that cities provide better water treatment and delivery infrastructure, and therefore make a basic level of drinking water more available. Our analysis indicated that big cities have a positive impact beyond this; renewable water resources also showed a strong positive correlation, although the mechanism is not obvious. It may be that big cities are better equipped to recycle water, maintain infrastructure that limits water wastage, and limit the negative agricultural practices related to water usage.

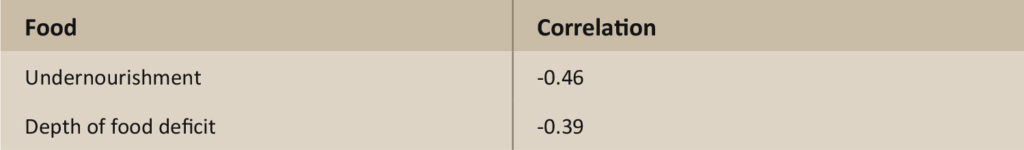

Food

Our analysis indicated that big cities have an affect on food in two ways. Firstly, they are associated with a decrease in undernourishment and, secondly, with a decrease in the depth of food deficit. Overall, big cities therefore appear to exert a positive effect on food security. This also offers some evidence that the movement of labour from agriculture to industry and services does not negatively affect food issues.

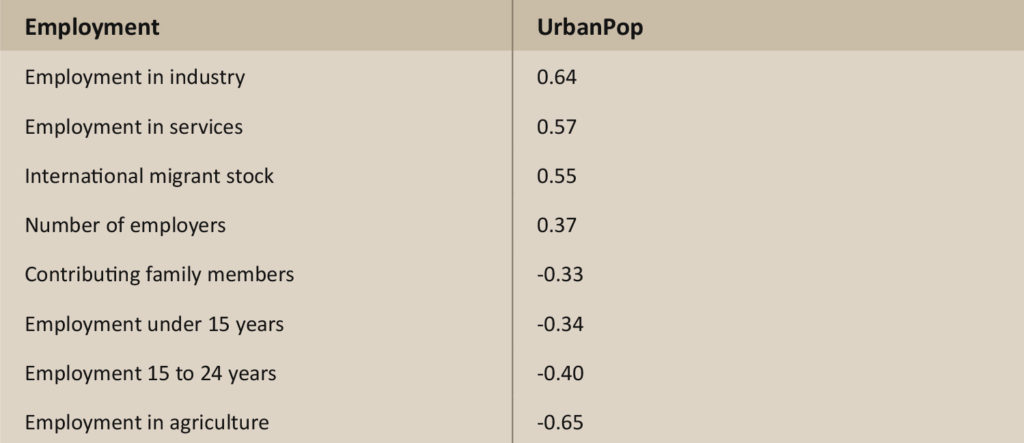

International migrant stock

Increased urbanisation is also associated with an increase in the international migrant population, who are likely attracted to big cities for reasons of employment and other factors. Indeed, urban areas offer a higher number of employers and quite possibly, therefore, a higher number of employment opportunities. There does appear to be some bias in the distribution or availability of these employment opportunities. Our analysis suggests that there is less opportunity for youth employment (15-24 years) in big cities. Big cities also appear to have the effect of reducing the number of family members that contribute to the family income. These variables suggest that big cities have a reconfiguring effect on families, and may reduce overall family well-being within the urban context.

Urban change

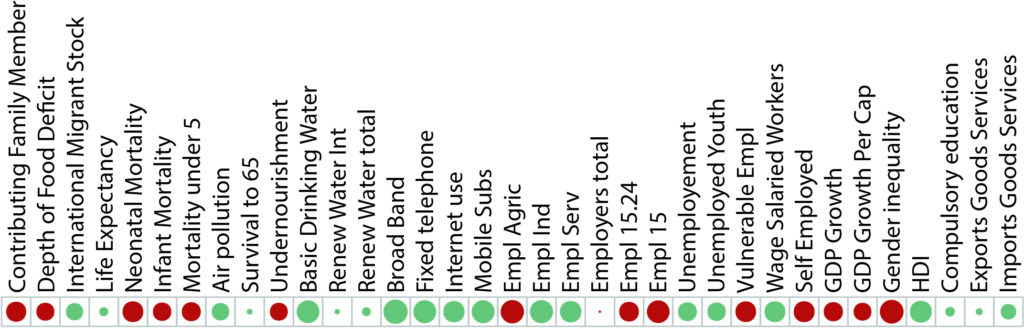

Having considered the impact of big cities in the African context, our analysis now turns to considering the growth rate of cities. We ran correlations using growth rate as the predictor, and the same list of well-being indicators as the outcomes. The idea was not only to gain some insight into the relation between growth and these well-being indictors, but, given the growth rate as predictor, more specifically to identify changes in correlations with these well-being indicators.

Figure 2: Urban change 1990 to 2016

Life expectancy

We found that increased growth rate was related to an increase in a range of life expectancy variables. These included overall life expectancy, which was strongly correlated with growth rate. This increase in life expectancy is likely related to a decrease in early-life mortality in the context of urban growth. These include a decreased mortality for neonates, infants and under fives. It was also found that survival increased when measured as reaching the age of 65.

Employment

There were a number of employment-related issues that were impacted by increased urban growth. These complemented the effects already identified in the analysis of the impact of big cities. In addition to these factors, urban growth had the effect of bringing youth employment down even further. It also boosted unemployment. It appears, therefore, that increased urban growth in big cities has a notable negative effect on this aspect of employment. On the more positive side, it was found that GDP per capita rose with increased urban growth rates.

ICTs

Urban growth also has a positive effect on the use of the internet, in addition to the effects already described in the analysis of big cities.

Others

It was also found that gender equality is boosted by increased growth rate, although the mechanism is not self-evident.

Discussion

The analysis presented here is, of course, not at all definitive of the situation with big cities in Africa. It has limitations regarding the number of countries presented, as well as limitations on the available data. It is, therefore, more of a thought piece than a conclusive piece of research. However, broad themes were identified and can be used as conversational trailheads. The broad themes identified included ICTs, water, employment, family, and health – although a range of other themes may have been excluded because of data limitations.

Big cities see an increase in the use of more advanced ICT technology, including internet and broadband connectivity. Urban growth boosted the use of the internet even further, in addition to the effects already described in the analysis of big cities. Big cities also see a rise in mobile subscriptions and fixed telephones. These findings point toward higher connectivity; although the jury is still out on whether higher connectivity is ultimately a positive factor (allowing a leapfrogging over development challenges) or a consumerist trap (in which the money spent to gain connectivity exceeds any true benefit).

An additional finding was that larger cities seem to be related to better availability of basic drinking water. This may be by providing better water treatment and delivery infrastructure, and they therefore make a basic level of drinking water more available. Renewable water resources also showed a strong positive correlation, although the mechanism is not obvious. It may be that big cities are better equipped to recycle water, maintain infrastructure that limits water wastage; and limit the negative agricultural practices related to water usage.

Big cities were also found to have an impact on employment. There was a strong shift evident in labour being diverted from agriculture to industry and services. Big cities are also associated with an increase in the international migrant population, who are likely attracted to big cities for employment opportunities and other factors.

It was also found that there was less opportunity for youth employment (15-24 years) in big cities, and urban growth had the effect of bringing youth employment down even further. It also had the effect of boosting unemployment. The number of family members who contribute to the family income was reduced. These variables suggest that big cities have a reconfiguring effect on families, and may reduce overall family well-being within the urban context.

Related to this, big cities appear to have an impact on food in two ways; they are associated with increasing nourishment (and decreasing undernourishment) and with a decrease in the depth of food deficit. Related to this, we found that increased growth rate was related to an increase in a range of life-expectancy variables. This increase in life expectancy is likely related to a decrease in early-life mortality in the context of urban growth.