In Mbizana, informal businesses keep some afloat

Last year, GGA published its first local government survey, which ranked South Africa’s 234 local and metro municipalities according to a select number of factors relating to municipal service provision, economic development and administration.

Inevitably, differences in the levels of administration, economic development and the services provided by councils around the country were identified. Of all the municipalities studied, the Mbizana Local Municipality, in the Eastern Cape, emerged as the lowest positioned in terms of the Government Performance Index (GPI).

This year, GGA decided to follow up on that research in an effort to provide useful data and insights to the community concerned and to a range of stakeholders involved in local governance. Given the need to bootstrap governance efforts in those municipalities most at risk, and mindful of its position, we decided to focus on Mbizana and aimed to conduct a 360 degree snapshot of the reality there.

We had another reason to concentrate on this municipality, given that it includes Nkantolo, the birth village of Oliver Reginald Tambo, whose centenary we wished to celebrate appropriately with some meaningful engagement to the benefit of citizens there.

To this end, in May 2017, GGA commissioned the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation (SLF) to collaborate and assist in developing and administering a business-survey tool to probe the informal economy. Using CommCare software, the tool was uploaded onto tables used by field researchers, who conducted the survey in June 2017.

Our study on the informal economy should, however, be framed relative to the “bigger-picture” perspective that we are aiming to develop by focusing comprehensively on the Mbizana muncipality.

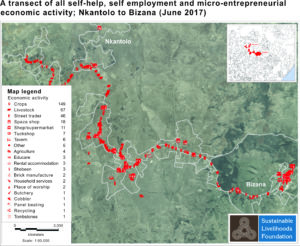

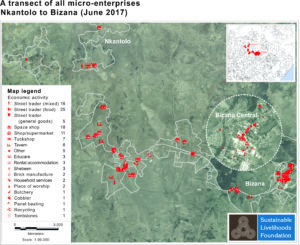

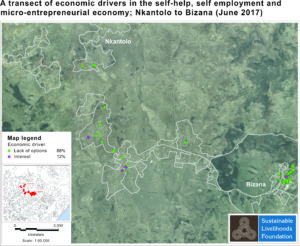

The Mbizana Business Survey Report that appears in this article is extracted from in-depth research that was done along an approximately 32km transect in the municipality, running from Nkantolo village to the central business district of Bizana town. The broader study was comprised of three components, all carried out along the afore-mentioned transect: a) a citizen survey with close on 1,000 participants; b) interviews with leaders in various sectors, and c) an informal business survey.

To frame the overarching context, the citizen survey was carried out with 947 individuals in households that represent home to about 5,506 people. The average income per respondent was R1,431 with the median income at R760. Some 854 or 90% of respondents disclosed their income.Their combined total monthly income was R1,222,390.80. (This figure included 87 students who reported income of R00.00.) The average household consisted of six people, with some households having as many as 23 people and others as few as one.

Given the high rates of unemployment and poverty, nationally and locally, the study aimed to ascertain how the people of this community were able to maintain themselves.The analysis given in this article focuses only on the informal businesses identified in the research site. A more detailed report on the entire research undertaken in Mbizana will be published separately in due course.

Suffice it to note that the business study strove to understand the nature and composition of livelihoods and business stakeholders, their operations and challenges encountered. It also sought to establish their interaction with and views of the local municipality. The findings are telling.

The community

The Mbizana municipality is located in the north-eastern corner of South Africa’s Eastern Cape, bordering KwaZulu-Natal. The Eastern Cape is, economically, the poorest province in South Africa, according to a 2016 study by the Institute of Race Relations, with a large part of its population living in rural conditions, often isolated from access to basic services.

Mbizana is about 200km from Durban and 500km from East London. It consists of a central town and surrounding villages, located along the R61 highway connecting the N2 national highway to the KwaZulu-Natal coastal boundary. The area can be classified as rural, with 95% of the population dispersed across the surrounding villages.

The population of about 281,905 people is spread across 48,557 households, covering an area of about 117 persons/km2 on average, according to the 2011 census. Several population groups live in the area, mainly people with Xhosa, Mpondo, Nguni or Sotho backgrounds. The Mpondo people are culturally dominant.

Along the course of the transect described above, the research took a small-area census approach, focusing on all micro-enterprises and self-help economic activities encountered within 100 metres of either side of the road.

The researchers GPS way-pointed all such businesses and, where possible, conducted interviews with the owners as they were encountered.

The researchers GPS way-pointed all such businesses and, where possible, conducted interviews with the owners as they were encountered.

Data collection was undertaken by a team of experienced researchers diverse in linguistic skills, racial profile and gender, supported by community members with local knowledge. Each day, the research team set out by vehicle, bicycle and on foot with electronic tablets containing the questionnaires, GPS devices, cameras and sound recorders, with the aim of comprehensively traversing the entire transect, including side roads and footpaths. In this way the researchers were able to capture a complete census of all enterprises in along the transect.

Where possible, the researchers sought to interview business owners. The business owner or representative was informed of the objectives of the research and interviews were conducted on securing consent. Most of the identified research participants agreed to participate in the study, though some refused to be interviewed.

The survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete. The questionnaires included both quantitative and qualitative inquiry, recording socio-economic and demographic characteristics and exploring themes of business characteristics, business challenges and local governance themes.

Open-ended questions and informal discussions allowed the researchers to inquire without unintended influence, which also allowed broader discussion to emerge. Interviews and discussions helped in learning about how the business models work. All waypoint, survey and qualitative data were then downloaded, analysed and classified in Microsoft Excel. Overview maps were developed in MapInfo GIS software.

General impressions of the site

Mbizana consists of a largely rural area, with a small concentration of people in a settlement and most people spread out across the vicinity. While there are several shops and workplaces around the central intersection in the town, most businesses found here are subsistence farms.

Of the 328 economic activities identified by the researchers, the majority entailed subsistence agriculture; over 200 separate smallholder activities were identified. The rest, which were the focus of this analysis, were cash-based micro-enterprises, including retail grocery outlets (spaza shops), street traders and liquor outlets.

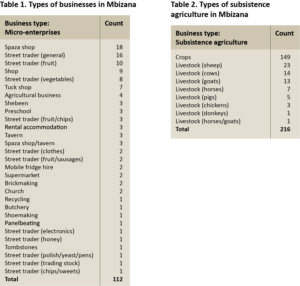

Not all respondents answered every question, and as a result certain questions provide partial information. The total number of businesses recorded in the survey was 112 (see Table 1 for a breakdown by type of business). The most predominant businesses were spaza shops, followed by general street traders. Taking all the different types of street traders together, this formed the largest group of business type.

Products sold by street traders varied widely, from clothes to honey and from electronics to sausages. Some 216 of the recorded livelihood-generating activities refer to other interesting examples of informal businesses, such as subsistence farming activities, most of which consist of growing crops or holding livestock (see Table 1).

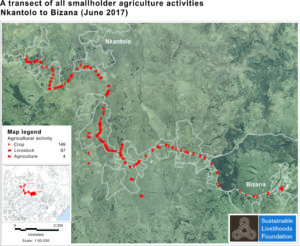

A transect of all smallholder agricultural activities, Nkantolo to Bizana (June 2017)

There was significant evidence of subsistence farming activities around the research site. These have been recorded to present a more inclusive picture, but do not correspond to further survey responses because there was usually no one present to provide answers. As demonstrated in Table 2, a large number of crops was grown in the area. In some cases, livestock was reared, predominantly sheep, cows and goats, and to a smaller extent horses, pigs, chickens and donkeys.

Gender

Gender

Gender was recorded for these enterprises, with the division being fairly equal – 49 female respondents and 51 male respondents. Ownership was also relatively evenly distributed. Some 60% of business owners were women, and 40% of business owners were men.

Gender dynamics are more skewed when taking nationality into account. Of the South African business owners whose gender was recorded, 60% were female – yet among the non-South African business owners, 91% were male, with no female, non-South African owners found during this survey.

A large majority (89%) of business owners were South African nationals. Much smaller groups of Ethiopian, Somali and Chinese owners were recorded, in addition to single Pakistani and Gambian owners.

The small businesses identified had relatively few employees. Of those who were working as employees, the majority (64%) were of South African descent, while a Somali, a Chinese and two Pakistani employees were also reported.

The large difference in numbers between owners and employees seems to suggest that most of these micro-enterprises were operating at subsistence level, where the business could not support a large number of employees.

Business trading strategy

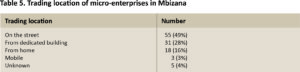

As seen in Table 5 below, about half (52%) of the micro-enterprises included in the survey traded on the street or were mobile traders. The second most dominant mode of trading among micro-enterprises occurred from a dedicated building, such as a shop. Some 16% of trade occurred from the home.

Economic situation of respondents working in micro-enterprises

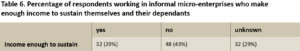

Of the 112 micro-enterprises surveyed, 80 provided a response to the question: “is this business enough to sustain you and your dependants?” Of these respondents, 48 (43% of total surveyed micro-enterprises) indicated that their income from working in the micro-enterprise was insufficient to sustain them and their dependants. Some 32 (29%) responded that their income was enough to sustain them and their families. Another 32 (29%) did not provide a response to this question.

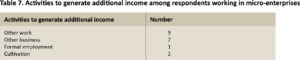

Only 19 of the respondents who indicated that their income was insufficient to sustain them and their dependants indicated that they were able to generate additional income. A number of the responses were categorised as “other work”, leaving it unknown whether this involved employment in the formal or informal sector.

Only one respondent indicated formal employment aside from their work at an informal business, and this was at the Department of Health emergency services. Several responses pointed directly to further activities in micro-enterprises, in the form of people who ran other businesses such as hair salons, moneylending, selling beer or washing clothes. Others generated further income through cultivation, grain and rice for example. This is unlikely to be supplemental income, but intended to meet household needs directly through subsistence farming.

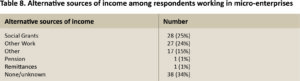

Seventy-four of the respondents said they had other sources of income, while some 25% of them relied on social grants. The fact that only 32 said they could sustain themselves from their micro-enterprises, combined with the low number of those who were able to generate further income, indicates that many people in Mbizana’s informal sector may be dependent on social grants, or that they are not always able to adequately sustain themselves and their dependants.

Further qualitative data supports the notion that many respondents lived at subsistence level. When asked on what they spent the biggest part of their income, nearly all respondents said their biggest expenditure was on groceries or “buying food”. Only a few indicated transport, clothes, rent or school fees.

People appear to use their income to meet their most basic needs. When asked about their reasons for starting a micro-enterprise or working at one, the majority said there were no other options. Some said they had gone into informal business because “there are no jobs”, others that “I was unemployed”. Other reasons provided were: “because I am poor”, “because I want to feed my child”, “I wanted to survive” and “it’s being desperate”. Only a handful reported starting a business out of interest or passion.

Most-traded products and highest-priced products

The most-traded products differed strongly per business, and a wide variety of types of goods was traded. The business type of most was self-evident: fruits and vegetables, or the basic foodstuffs supplied by spaza shops. Most- traded products are of little monetary value. Most prices fell below R100. An electronics shop reported its highest priced product was R1,000.

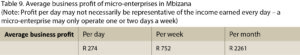

Average business profits

The average reported profits from the micro-enterprises included in this survey suggest that income from these businesses, though relatively low, was likely making an important contribution to local livelihoods. These findings are in accordance with the earlier discussion, which found that income from micro-enterprises in Mbizana was often supported by social grants or other business activities, and supplemented by subsistence agriculture. In some cases this was simply insufficient to sustain even basic needs.

A transect of economic drivers in the self-help, self-employment and micro-entrepreneurial economy Nkantolo to Bizana (June 2017) micro-enterprises in Mbizana was often supported by social grants or other business activities, and supplemented by subsistence agriculture. In some cases this was simply insufficient to sustain even basic needs.

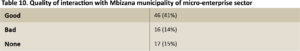

Municipality: service provision satisfaction

Despite Mbizana’s status as the worst-performing municipality in South Africa, according to GGA’s 2016 Government Performance Index (GPI), some 41% of the respondents described their interaction with the municipality as “good”, and only 14% reported their interaction as “bad”. However, the qualitative comments suggested that the standard to which the municipality was held was extremely low.

People describing their interaction as good commented that this was because “every time they come they are friendly”, “so far so good”, “I pay low/ no rent/wages”, “the councillor is accessible”, or even “they do nothing bad to me” and “they don’t give any problems”.

It would appear that the absence of direct harassment by government influenced people’s perception, rather than quality of the services the municipality provided. Those who did describe the interaction as “bad” mainly commented that this was because “the municipality does not provide anything”, “they do nothing” and a “lack of care”.

Almost all answers to the question “what could the municipality do to provide a better environment for business?” mentioned cleaning. Respondents commented that providing cleaners or cleaning the environment would help, alongside repeated mentions of installing water taps, electricity, and providing shelter or buildings.

Nine people reported being affected by crime, most of them by theft and one whose goods were damaged. Opinions of the police varied, with some reporting their satisfaction and others not feeling helped enough. Most comments from those unhappy about their interaction with the police refer to relatively benign incompetence, such as “they came hours after something happened”, “they take time to help” or “we saw the suspect walking around the same day he was arrested”.

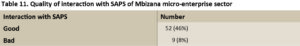

Other replies may point at more problematic interactions with police. Some respondents commented that “The SAPS take my things if I don’t pay rent to the municipality”, “they stop me from running my beer business” and “they normally come for business licences and do raids”.

Some reported being left alone by the police after they had stopped their involvement in an illegal activity such as running a shebeen, or had obtained a licence to trade. These comments suggest that police activity could be seen to have created an environment that was hostile to local entrepreneurship and the development of micro-enterprises.

Further inquiry suggests that respondents took the question about their “interaction with the municipality” literally to mean the quality of any personal contact with representatives of the municipality. When respondents were asked more detailed questions on the quality of municipal services, a different set of answers emerged. These questions were derived directly from the municipality’s own mission statement and list of goals to be achieved.

The Mbizana municipality website states the following as the municipality’s mission:

Mbizana aims to be a flourishing local municipal area with a growing employment creating economy and sustainable communities where everyone has access to equal opportunities. The Municipality strives to be transparent and open in all dealings. Mbizana Municipality makes efforts to integrate and incorporate women in key decision-making roles within the institution.

This vision translates into six goals that the municipality aims to achieve:

a) investing in its people poverty fight [sic];

b) providing affordable services;

c) facilitating a people-driven economy;

d) building sustainable communities;

e) protecting and preserving its environment;

f) strengthening a culture of performance and public participation.

The true state of municipal services becomes apparent from the answers to questions concerning people’s satisfaction with various municipal services and infrastructure based on these six goals.

The overwhelming response was “dissatisfied”, with a few counts of “room for improvement”. Spread over the six questions, there were only a few instances where someone reported being satisfied with the municipality’s performance. All the other responses were negative.

Taken together with the comments on interaction with the municipality, a picture of severe disillusionment emerges. On the one hand, people seem to have low expectations in their dealings with government. As long as they are not interfered with or directly harrassed, many considered their interactions with their local government to be good.

On the other hand, their sense of what should fall under the municipality’s responsibility was extensive. For example, many commented that they looked to the municipality to provide jobs and shelter. The municipality can be said to have invited such expectations by aiming for a “growing, employment-creating economy”, while the goals it set for itself were far from concrete, and open to interpretation.

The question arises: how much a municipality such as Mbizana, give its remoteness, geographical isolation and the context of poverty that surrounds it, be expected to do? The widespread dissatisfaction expressed by many citizens suggests that the municipality needs to set more clearly defined and attainable goals, especially where micro-enterprises and local entrepreneurship is concerned.

Conclusions

Informal businesses in Mbizana operated mostly at a subsistence level, with business profits averaging R2,261 a month. Businesses were concentrated around the town centre, with activities centred around subsistence agriculture spread out more widely.

Most micro-enterprises were run by South Africans and had very few or no employees. Only 32 respondents were able to sustain themselves from their business profits; others relied on social grants, subsistence agriculture or simply had to endure insufficient economic resources.

Meanwhile, it appears as if the picture painted is one characterised by survivalist economics, where the average business brings in little more than a social grant, relies on trading food and beverages, and where those in the informal sector have to hold down multiple jobs to remain afloat. Despite reporting superficial satisfaction with local government, the profound dissatisfaction reported by business people concerning the municipality’s own projection of itself is telling and suggests that significant room for intervention and improvement exist.

Our forthcoming, comprehensive report that details citizens’ experiences of local government in Mbizana, fleshed out by qualitative interviews, stakeholder consultation and community responses, will provide an apt entry point both for promoting this positive transformational agenda and for catalysing further inclusive participation and targeted engagement.