South Africa: lessons from history

South Africa’s history syllabus had to be replaced after apartheid ended, but new recommendations could be a step back into the past

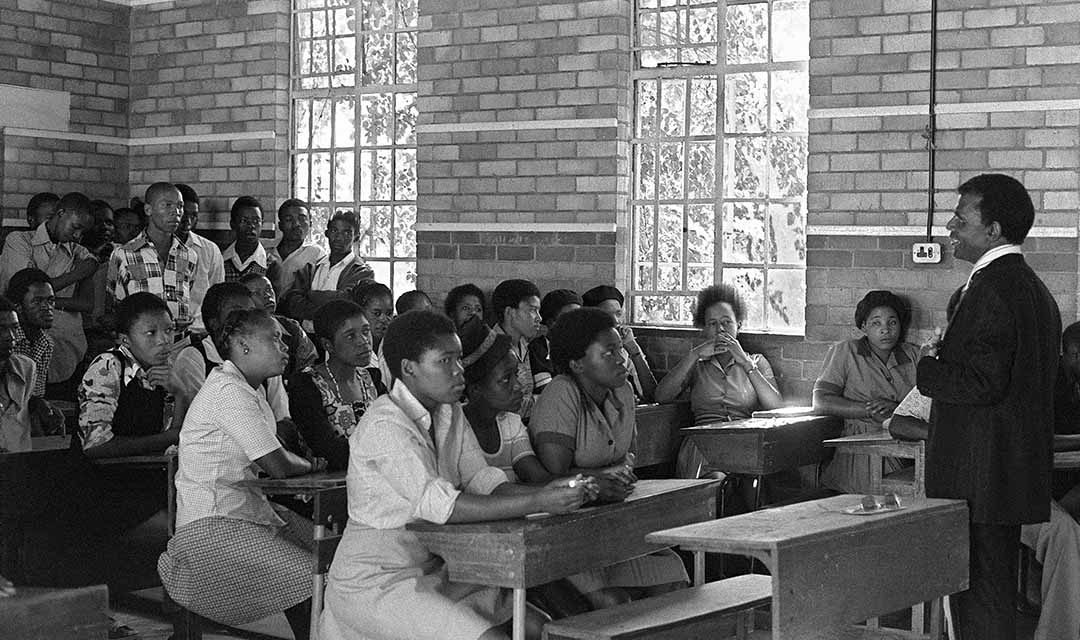

Students at Orlando High School in Soweto in May 1977 are addressed by a teacher (R). Soweto students had made international headlines in June 1976 when thousands of schoolchildren marched through the streets in protest against the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in the township schools and were shot at by the apartheid police. Photo: AFP

All governments, no matter the country, try and impose themselves on the history curriculum and especially in the history textbooks, said Barry Firth, educationist and chair of the South African Society of History Teaching, in an interview at CPUT Campus in Cape Town, where he lectures history, in July this year. Firth’s assertion is nowhere more evident than in the South African apartheid government’s insertion of the myth of the Afrikaners as the chosen people into its National Christian Education history syllabus. Apartheid-era textbooks like those written by the late teacher and author AN Boyce offer ample evidence of this, as academic Richard Chernis points out in his thesis, History Teaching during the Period of National Party Rule 1948-1990 (University of Pretoria, 1990).

Chernis cites Boyce, saying [Boyce] “uses the terms ‘problem’ and ‘trouble’ ad-nauseam when referring to the role of non-whites in South African history: the ‘Basuto problem’, the ‘native problem’, the ‘Sekukhuni problem’, the ‘Indian problem’ and the ‘Bantu problem’. Boyce later admitted to his earlier bias. He was quoted by BL Molyneaux in his 1994 book, The Presented Past: Heritage, Museums and Education, as saying: “I am not proud of some of the chapters in my earlier books, but I am trying to correct the mistakes I made and I have changed some of my previous interpretations”. This approach was not unique to South Africa. African countries freeing themselves from the shackles of colonial history have also struggled challenges in retelling their history.

This is reflected in educationist and academic Ronald Ndille’s 2018 article for the SA Society for History Teaching journal, Yesterday&Today, ‘Our schools our identity: efforts and challenges in the transformation of the history curriculum in the Anglophone subsystem of education in Cameroon since 1961’. In his article, Ndille cites several challenges Cameroon has faced in transforming its history curriculum in schools and universities. One of the “stumbling blocks”, he says, “rests on the fact that Cameroon is a country of over 260 ethnic groups with mutually unintelligible languages sitting about a kilometre apart in some areas”. But, he adds, Cameroon’s political elite posed a “much more serious hindrance” to curriculum reform. “A majority of those called upon to design school programmes were people who received colonial education,” he writes.

“Evidence of the initial curriculum reform of the 1960s demonstrates a semblance with the colonial curriculum, implying that when the new elite were called upon to design the history programme soon after independence, they carefully replicated what they had acquired as historical knowledge and have since found it very difficult to move away from it.” Ndille concludes by saying that while efforts at reform have been made at every level in Cameroon, transformation of the history curriculum envisaged in policy documents after independence has not been achieved. The overall theme of both colonial and apartheid syllabuses was that black people were participants in white narratives. It was not only in the text and ideology, but in the philosophy surrounding teaching as well; in the apartheid/colonial state the teacher driven approach governed what was being taught.

Teachers were the custodians of knowledge and learners the receptacles. The curriculum, designed around the regurgitation of “facts” and dates dictated by the teacher, made no space for reflection, debate or discussion. After the end of apartheid it was clear that South Africa’s history syllabus had to be replaced. Its first attempt, Outcomes Based Education (OBE), put the learner in the centre of learning. But OBE implementation proved a challenge to both learners and educators; teachers from the apartheid era, for example, struggled with the learner-centred system. OBE was followed by a new National Curriculum Statement (NCS), Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement, (CAPS), which was adopted by the then education minister, Kader Asmal, in 2011. CAPS was to change not only the content, but the way history was taught, describing the subject as, “about learning how to think about the past, which affects the present, in a disciplined way.

History is a process of enquiry. Therefore, it is about asking questions of the past: What happened? When did it happen? Why did it happen then? What were the short-term and long-term results? It involves thinking critically about the stories people tell us about the past, as well as the stories that we tell ourselves.” The CAPS document outlining the curriculum for high school grades 10-12 said the specific aims of history were to equip students with knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the past and the forces that had shaped it, providing them with an understanding of historical concepts, including sources and evidence, and equipping them with the “ability to undertake a process of historical enquiry based on skills”. University of Cape Town history education specialist Prof Rob Siebörger, who helped develop CAPS, argues it is the international benchmark for the way history is taught.

But the CAPS philosophy is dependent on a number external factors: the training of the teachers, the culture of the school, the ability of students to comprehend the concepts, the ability of educators to teach the concepts, and the way in which the textbooks are written to initiate discussions. In South Africa, this international standard is being placed on an education system racked by inequality, where most learners are taught in their second language. Both Barry Firth, quoted in the opening paragraph, and Siebörger agree it is the schools with means that get the full benefit of the system – others have a longer and harder journey. A study by educationists Johan Wasserman and Denise Bentrovato, ‘Confronting Controversial Issues in History Classrooms: an analysis of pre-service teachers’ experiences in post-apartheid South Africa’ (2018), illustrates the challenges educators face in implementing CAPS. The study interviewed 75 pre-service high school history teachers who had undertaken the practical teaching component of their education degrees.

The research revealed that the student educators were totally unprepared for teaching controversial issues. The entrenched biases of the schools and the locked-in racial views of the students – and mentor teachers – led to heated confrontations, meaning the aims of the CAPS method were not fully realised. In an article published in 2018 in the journal Yesterday&Today, the researchers said the experiences of the 75 student teachers varied greatly for numerous reasons, including the institutional culture of their placement school and their relationship with their mentor teacher. Their experiences, however, highlighted the centrality of race in addressing controversial issues, reflecting the deep-rooted legacies of apartheid. “The consequences of this was a black/white binary that continues to influence the way certain schools, pre-service teachers, mentor teachers and learners relate to history and to each other,” Wasserman and Bentrovato wrote.

However, Firth argues that a discussion in the hands of a grounded teacher, even using the discredited AN Boyce textbooks, can spark a deep discussion; that the positioning of the question elicits debate and discussion. As a high school history teacher in Carnarvon, a rural South African town, he successfully did this with classes of students from vastly different backgrounds. CAPS itself is now under scrutiny by a ministerial task team (MTT), reappointed by Basic Education Minister Angie Motshekga in December last year following the same team’s initial report, which contained several recommendations aimed at making South Africa’s history curriculum more Afrocentric and relevant to South African students. One of the MTT’s initial recommendations was that history should be phased in as a compulsory subject for grades 10-12 by 2030. It also criticised the current curriculum because the “South African content avoids controversial and problematic issues.

This undermines the fact that a multi-perspective approach is relevant in history”. The MTT report also said the CAPS curriculum made the topics and themes on Africa too “touristy” and were taught to students “too early in their lives”, in the lower grades. The reappointed MTT will be responsible for formulating a new history curriculum for grades 4-12 as well as screening text books to ensure they align with the new curriculum, as well as proposing history teacher training programmes. But the first MTT report has not gone unchallenged; educationists and commentators have criticised what they describe as “contradictions” in the report. For example, very much in step with CAPS principles and methodology, the report states that: “History should not be used for political expediency and that its particular role in developing critical thinking be affirmed and defended….. history education at school has the potential to offer explanatory, analytical and interpretative skills.

Ideally, learners have to be capable to assess arguments and develop an ability to construct counter-arguments which have to be synthesised within an historical narrative. They need to be aware of the nature of historical evidence, conflicting evidence and historical interpretations, and in the process they should develop a sense of historical perspective. This is because history is a problem-solving discipline of a specific kind.” Elsewhere in the report, however, the MTT attacks CAPS: “….biased towards the liberal school of thought as a dominant historiographical paradigm in South Africa. This is the hidden curriculum defining CAPS and it is connected to the intellectual traditions of western liberalism and its idea of human hierarchies, individual liberty and private property.” Thus, the MTT apparently advocates for a teaching of African nationalism, which it suggests is more benevolent than Afrikaner nationalism; the report is silent on how this proposed new curriculum should be taught.

It is no surprise then that the minister has extended the MTT’s term for it to iron out the contradictions in its own findings. Firth points out that even if CAPS is scrapped and those with a political agenda get their way, they will still have to overcome the very real challenges South African teachers face trying to teach history – lack of resources, training, time and a system that rewards pass marks instead of comprehension and debate. Changing the syllabus will not make these problems history.