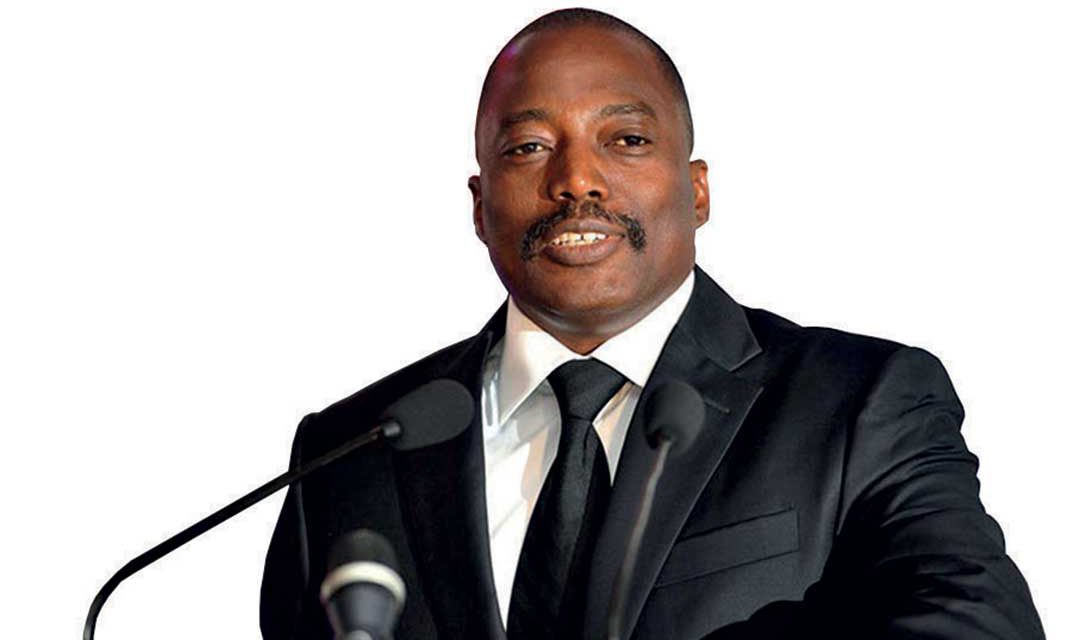

While the DRC president is seen as aloof and alienated from his people, few doubt his ability to manipulate the political system

One morning last November, Joseph Kabila’s motorcade bullied a path through Kinshasa’s traffic towards the Palais du peuple, which houses both the Senate and National Assembly. The Congolese president rarely ventures into public view and speaks even less frequently but he wanted to reminisce about his 16 years in power.

At the Palais, Kabila told legislators that he had inherited “a country in tatters … a non-state” bedevilled by a “vicious circle of hyperinflation and the depreciation of the national currency”. He claimed to have stopped a civil war and re-established the unitary state, midwifed the adoption of a new constitution and the birth of democracy, and presided over years of uninterrupted economic growth. This autobiography – the protagonist as pacifier, unifier, nation-builder – was received raucously by the president’s partisans.

True, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly known as Zaire, was in an infernal condition in January 2001, when Kabila succeeded his father, Laurent-Désiré, who had been assassinated by a bodyguard. Just 29, Kabila unexpectedly found himself head of a vast state shorn of huge chunks controlled by rebel armies backed by Uganda and Rwanda. Internationally-mediated efforts to end the war had stalled under the bombastic Kabila père.

The arrival of the little-known son, then chief- of-staff of the land forces, “unlocked a lot of progress”, says Stephanie Wolters of the Institute for Security Studies. The world embraced Kabila, who met with Nelson Mandela and Jacques Chirac in the first couple of months of his presidency.

He allowed a UN mission to deploy throughout the country, a confidence-building process his father had resisted. “There was a strong desire to prop up this young guy and flood him with positive messages to get him to play the game his father hadn’t wanted to play,” says Wolters.

This political neophyte also enjoyed the goodwill of a population exhausted by conflict.

“I was in exile in Cape Town and I asked my church to pray for him,” says Albert Moleka, a former heavyweight in the Union for Democracy and Social Progress, Congo’s oldest and largest opposition party. “Everyone wanted to give him a chance,” he says. “It was an opportunity for the country with this young leader to break with the autocratic regimes of Mobutu [the dictator who ruled from 1965 to 1997] and Joseph’s father.”

Benefitting from international pressure, Kabila brokered the withdrawal of Rwandan and Ugandan troops and concluded a peace deal with the rebel groups, the Rally for Congolese Democracy and the Movement for the Liberation of Congo, at Sun City in South Africa. In July 2003, a transitional government was installed in which Kabila shared power with four vice presidents, among them the leaders of the RCD and MLC.

“The one thing Joseph Kabila did well was the unification of the country,” says Mvemba Dizolele, a Congolese lecturer at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. “He brought the various factions together and unified Congo.”

DRC Kinshasa 28th of November 2011. Elections Day, Voting Day and Ballots counting. MONUSCO / Myriam Asmani

The Congolese voted overwhelmingly for a new constitution in December 2005 and a year later Kabila triumphed in the country’s first democratic elections since 1960. “The international community moved quickly to organise the elections to give Kabila a modicum of legitimacy and legality,” says Dizolele of the polls, which were almost entirely financed by international donors.

If most observers can sympathise with Kabila’s interpretation of the early years, they’re less indulgent towards the presidential version of what followed— the period after he had consolidated power and legitimacy.

High mineral prices have underwritten sharp growth through much of Kabila’s elected presidency, peaking at 9% in 2014, but those heady days are over. Low copper and oil prices slashed growth to 2.5% in 2016 while the Congolese franc has shed half its value against the dollar since 2016 and inflation has leapt to over 25% after several years of stability.

The Congolese, currently being pummelled by deteriorating purchasing power, now wonder what the boom years brought them. “The international organisations kept on saying that Congo is one of the fastest growing economies in the world, but every year we go from crisis to crisis and the growth is not reflected in everyday life,” says Dizolele.

International donors and direct payments by households continue to finance 80% of the health sector, while households fund over 70% of education spending. The government’s annual budget has never exceeded $9 billion, a paltry sum for a country of between 75 million and 85 million people. Currently public spending is about half that figure. Unemployment remains stubbornly high and most provincial capitals are still unconnected to Kinshasa by paved road.

When pressed to name the president’s economic achievements, even Tryphon Kinkiey, a prominent pro-Kabila parliamentarian, struggles to think beyond the rehabilitated international airport and Boulevard du 30 Juin—both in Kinshasa—and the creation of Congo Airways, a state-owned airline that flies between the DRC’s main cities. “There are international class hotels which didn’t exist before,” he offers.

The common feeling that Kabila and his friends have lavishly enriched themselves compounds the sense of injustice. Last December, an investigation by international news agency Bloomberg uncovered at least 70 companies belonging to the Kabila clan and active in sectors including agriculture, mining, banking, real estate, telecommunications and aviation.

Several months earlier New York hedge fund Och-Ziff had to pay a hefty fine in the US for spending more than $100 million on bribing Congolese officials, including a $10.75 million payment to “DRC Official 1” – understood to refer to the president.

The commodity boom was “a lost opportunity, because Kabila not only became a political head of state but also a wheeler dealer who integrated himself into business networks,” says Jean Omasombo, a Congo expert at the Royal Central Africa Museum in Belgium.

The legitimacy which was the outstanding accomplishment of Kabila’s first half-decade in office has been in steady decline for years. Now, it has almost evaporated. The result of his first election is widely considered to have been sound, but the polls in 2011 were riddled with irregularities and the Carter Center concluded that the results were not credible. “Congolese public opinion was against him for having badly managed his first mandate … and he got through the election by fraud,” says Omasombo.

African heads of state swiftly endorsed Kabila’s re-election. Soon after, the UN, the US and the EU accepted the result but, for the West at least, the relationship had soured. “They [the US and EU] felt cheated and afterwards it became very difficult for Kabila to get their support,” said Moleka, who served as chief-of-staff to the late Etienne Tshisekedi, the runner-up in the 2011 election.

As Kabila stepped up to the lectern last November, he was five weeks from the end of his second term, the constitutional limit for a Congolese president. Elections had been delayed, with the government blaming logistical and financial constraints. It was apparent that Kabila would remain in office beyond the expiration of his mandate on 19 December. More than six months later, Kabila was still ruling in legal limbo, and fears are pervasive that he plans to remain in power indefinitely, likely through a referendum to remove term limits or modify the manner in which the head of state is chosen.

However, Kabila’s backers would be unlikely to prevail in a constitutional plebiscite without resorting to unscrupulous tactics. In October 2016, a Congo Research Group (CRG) poll showed that only 16% of those consulted supported a change to the constitution. An updated survey released in May last year found that 69% thought Kabila should have given up power at the end of his second mandate. The president can indeed take some credit for enacting the constitution in February 2006, says Dizolele. “It was an important step because today this same constitution is blocking him,” he notes wryly.

Despite the widespread misgivings, the president’s supporters insist that Kabila intends to abide by the constitution and hold elections as soon as conditions allow. On New Year’s Eve, Kabila’s parliamentary coalition and the opposition signed a deal which scheduled elections for late 2017 but it is hard to find anyone who believes they will happen.

The electoral commission has estimated that the full electoral programme will cost $1.8 billion. However, few are convinced by these calculations, which are often cited by presidential allies as an obstacle to holding the election. Fed up, the EU and US have imposed targeted sanctions on some of Kabila’s top officials for undermining the electoral process and violating human rights.

Unmoved, the president has steadily co-opted and fractured the Congolese opposition by offering enticing ministerial portfolios to former adversaries. However, Kabila has avoided ceding control of key departments such as finance, justice, mines, defence and interior.

But the president’s ability to manage the Congolese political class far outweighs his capacity to control public opinion. CRG’s two recent polling exercises affirm anecdotal evidence that Kabila is deeply unloved throughout the country. According to the research, the incumbent would secure between 8% and 10% of the vote if a presidential election were held right away.

The president has always had a distant relationship with his countrymen and once perhaps this was a sign of dominance. “He speaks when he decides to speak and he shows up when he wants to show up,” Moleka says.

But today, Kabila’s characteristic silence infuriates a population who increasingly see him as an impostor on the throne. “You don’t feel like Kabila is rooted in this country and that’s his main problem,” claims Moleka. “Kabila is like a work of art … Others speak in his name,” says Omasombo.

Kabila’s DRC is a country of escalating repression and instability, a trajectory which has coincided with the president’s diminishing legitimacy. Security forces crushed street demonstrations in Kinshasa with lethal force in January 2015 and September 2016, killing more than 50 on the second occasion. Public protest is currently outlawed in much of the country and several political rivals have been jailed or gone into exile.

Various parts of the DRC have been traumatised by armed groups throughout Kabila’s presidency, though the destruction has generally been confined to the east. Since August 2016, however, the Kasai region in central southern Congo has been terrorised by fighting between the state and an anti-government militia known as Kamwina Nsapu.

Over 1.2 million people have been displaced by the conflict, which now affects five provinces. UN investigators have found at least 40 mass graves, reportedly dug by the Congolese military after clashes. “Right now Congo is at its most volatile and explosive point for 20 years,” says Dizolele.

The Kabila regime’s unpopularity might eventually encourage the president to abandon plans to cling on to power. But the DRC’s dysfunction could well be the president’s friend – as Kinkiey, Kabila’s ally, explains. “We should have a national debate about what type of elections we organise,” he says, claiming the cash-strapped government cannot afford the current arrangement.

Kinkiey suggests that the country would save money if the president were not to be elected by universal suffrage but rather, appointed by parliament, a constitutional reform which could wipe Kabila’s slate clean and permit him to re-legitimise his tenure.

“Today we are faced with reality,” Kinkiey says. “Water is lacking, electricity is lacking, healthcare is lacking, roads are lacking. The misery is real and the budget is nil.”