The 1950s, 60s and 70s were a heady time for Africa, as the continent broke free from the shackles of colonialism after more than a century of formal European rule following the 1884-5 Berlin Conference.

Leaders in the vanguard, such Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, whose country was the first to gain independence in 1957, Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere and Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta – brimming with “hope, optimism and confidence” as one of our contributors, Issa Sikiti da Silva, describes it – promoted pan-Africanism, a commitment to political and economic unity, including support for those countries yet to be liberated from colonial or white minority rule.

But decolonisation was a messy business, even in countries that gained independence without a bloody or protracted liberation struggle.

It is against this background that this edition of AIF seeks to examine the legacy of Africa’s liberation movements and independence parties, and the extent to which they continue to influence contemporary politics on the continent. Our writers, from different perspectives, ask the question why, after more than five decades of freedom, too many of Africa’s citizens remain imprisoned by poverty, underdevelopment, bloody regional conflicts and authoritarian governments ruled by ageing despots who at best pay lip service to the notion of multi-party democracy?

Why have former liberation movements been unwilling or unable to transform themselves and their countries into well-governed, fully functional democracies? Why is power all too often concentrated in the hands of corrupt elites, and most importantly of all, why do their citizens put up with them?

In his opening article, William Gumede examines why African voters continue to elect tyrants and authoritarian governments. He attributes this phenomenon to the “mass trauma” of colonialism, one feature of which is that people are so terrified of being shut out of patronage systems that they are intimidated into voting for the status quo. “The irony is that the impact of the trauma of colonialism has brought many African leaders to power who mimic the oppressive behaviour of their former oppressors,” he writes.

Da Silva writes that the failure of liberation movements to meet the challenges of the democratic era and face the harsh realities of contemporary politics and socio-economic development dynamics has meant they’ve been unable to meet peoples’ needs, especially in the context of rapid urbanisation across the continent.

The sense of betrayal many Africans feel is summed up in a quote from a disillusioned former liberation activist in Angola, now 75, who tells da Silva: “all the enthusiasm, joy and hope that held up our spirits have gone up in smoke.”

For this edition Owen Gagare conducted several face-to-face interviews with veterans of Zimbabwe’s liberation war. He quotes the late leader Joshua Nkomo, who died in 1999, from his autobiography, who said: “the hardest lesson of my life has come to me late. It is that a nation can win freedom without its people becoming free.” All of the veterans interviewed had no regrets about their part in the struggle for freedom, but all but one expressed their disappointment at the current state of governance in the country. “My participation in the armed struggle was not in vain,” Zipra veteran Baster Magwizi, told Gagare. “It brought about independence even if we may not be free.”

Francois Misser writes that the discipline imposed during times of struggle within the liberation movements and the need for strictly hierarchical command structures shaped the one-party states that became a feature after independence, facilitated by the involvement of the Soviet union, its allies and china. He reminds us that many of those liberation movements remain in place as the ruling party as in South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

Misser also notes that liberation movements played a role in promoting women’s rights both out of necessity and for ideological reasons. Yet a darker legacy of Africa’s fight for independence has been a culture of violence, including against and women and children in armed conflicts, as well as widespread use of child soldiers.

Efforts by Nyerere and other first-generation leaders to unify their newly independent countries by the centralisation of power also contributed to a proliferation of one-party states. Creating new national identities was always going to be a challenge given the artificial nature of Africa’s colonial borders created with no respect for longstanding ethnic, cultural and linguistic divisions. The legacy of some of these has been profound and often toxic, while five decades of centralised power has helped to create a climate where political parties support the people’s vote if they win and cry foul if they don’t.

Another legacy of the centralised mentality of post-independence parties is the reluctance of old-style “Big Men” to step down, instead changing their constitutions to allow themselves more terms in office and using the judiciary and the military to stifle opposition parties and voter rigging behind a façade of regular elections.

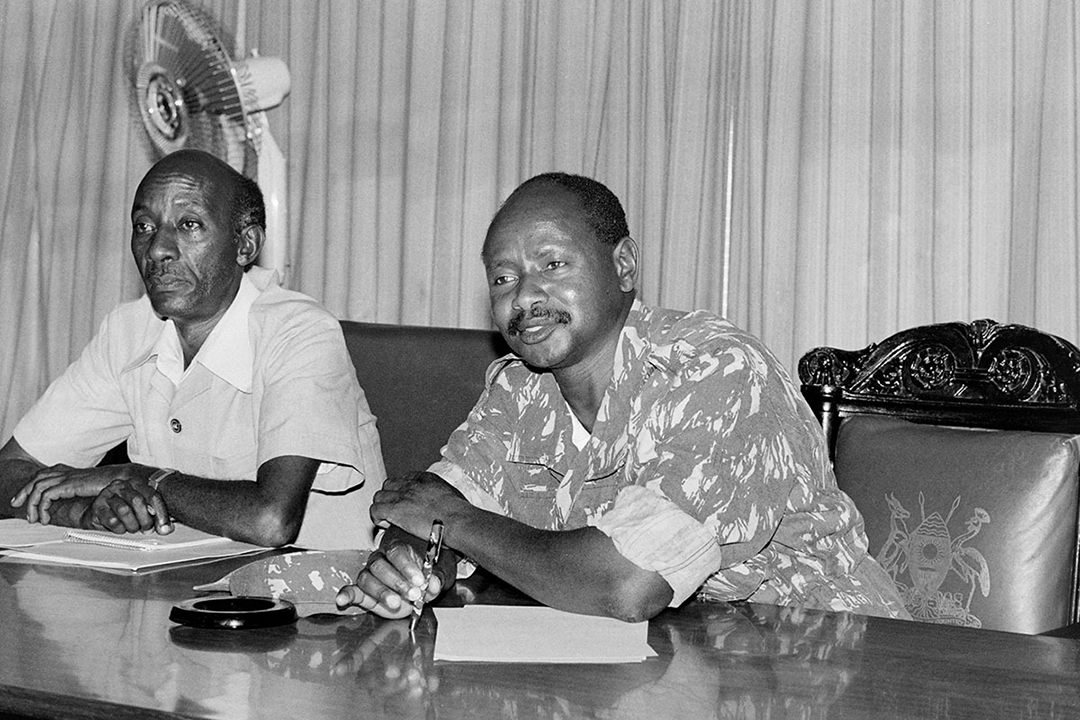

Contributor Blame Ekoue writes about one obvious example, Togo, where the Gnassingbe family has ruled the country, from father to son, since 1967. In Cameroon, meanwhile, President Paul Biya, 88, has, says Amindeh Blaise Atabong, managed to cling to power by a strategy of “presidential silence” over the burning issues affecting his country, including the brutal crackdown on Anglophone dissidents and the COVID-19 crisis. As people lose hope in the system, Atabong says, fresh dissent is brewing in various parts of the country. And as he notes, Biya’s longevity in power is not incidental to the support he enjoys from Cameroon’s former colonial master, France. Another member of this club is Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni.

Using Ethiopia and Zimbabwe as examples, analyst Nick Branson says the militarisation of politics in some African states that evolved out of liberation wars will continue to undermine political stability in these countries unless ruling parties commit to constitutional safeguards, which keep soldiers in the barracks, rather than allowing them to enter politics or do business with the state. For another view on this subject, read political analyst Linos Mapfumo’s article, ‘The Military, Politics and Power’.

In Angola, Ini Ekott writes that while the new president, Joao Lourenco, initially made some reforms, notably steering Angola away from the familial patronage system under Jose Eduardo dos Santos, the MPLA is still the ruling party and intends to stay that way. An indication of this, analysts and opposition activists say, is ongoing attacks on dissidents. The ruling party also persists in delaying promised local elections, which would likely see it lose control over sub–national governments.

So, the question must be asked: is Africa doomed to be constrained by past glories and old loyalties, ruled by parties who rely on their struggle credentials to stay in power even as they fail to deliver? Well, there are signs that change is not only possible, but stirring. For a start, as the World Bank noted in a report late last year, sub-Saharan Africa is now home to more than a billion people, half of whom will be younger than 25 in 2050.

And as Ronak Gopaldas points out in his article, in the case of South Africa, the electorate has changed significantly since the African National Congress (ANC) came to power. Young voters do not remember the struggle their parents and grandparents fought and feel less affinity and loyalty to the liberation party. This, as well as greater urbanisation and a declining rural voter turnout, make a future era of coalition politics a real possibility. The ANC, bedevilled by allegations of corruption, economic mismanagement, patronage and non-service delivery, has already seen its national majority eroded in recent elections and it lost three major municipalities in the 2016 local government elections.

Interestingly, as Frederico Links writes, something similar appears to be happening in Namibia, too. The liberation party, Swapo, held sway since independence in 1990 until it narrowly lost its two–thirds majority in the national assembly in elections in late 2019. Links says that party members opposed to the current leadership are openly calling for a Swapo government to be recalled, including a group called the Namibia Exile Kids Association, made up of children of former liberation leaders, who have called for the “ship to sink”.

Meanwhile, in Nigeria, Paul Adepoju writes, a new generation unhappy with the current leadership has harnessed social media to form a decentralised movement for change, including recent protests against police brutality. Adepoju’s article examines how these protests echo the grievances that fuelled Nigeria’s ruinous civil war in 1967-70, fought between the secessionist south-eastern state of Biafra and the federal government.

However, while anger with bad governance in all its forms are real and present across the continent, and for many economic freedom remains elusive, it is important to recognise the progress that has been made since the independence era.

Raphael Obonyo’s article notes that despite having to shake off the dire socio-economic legacies inherited from colonialism, including arbitrary borders, single crop economies and corrupt elites, the continent is transforming itself. He reminds us that in 2018 Africa was the world’s second–fastest growing region, experiencing an average annual GDP growth of 4.6% for the period 2000 and 2016. Then came COVID. Nevertheless, the African Development Bank says that economic growth could rebound to 3% in 2021, provided governments manage the infection rate well.

Ultimately, African governments would do well to take note of a point Gopaldas makes in his article: “In the life of every liberation movement there is an inflection point where past performance and history counts less than future service delivery.”

Interesting reading

Is African really liberated?

Perhaps that should be the question.

We need to join hands and form the country africa, a boderless continent as in the vision of Gaddafi, His rule might have not been the greatest but he had a great vision for us. Total break away from white influences. He was killed for this, now Libyans cry, now africa remains chained, our leaders want to be the highest command hence keep the agenda at bay and make plans for 2063 when they will all be dead so no one can hold them accountable. We need to do this now join a federal Republic of Africa be a superpower in less than a century. With the wisdom of our ancestors we will make it.