To understand the present, one needs to understand the past. Surely this aphorism is true across cultural and other divides?

To understand the present, one needs to understand the past. Surely this aphorism is true across cultural and other divides?

As this edition on African history started taking shape, the question arose: Do those of us who seek a prosperous future for the continent have a sufficiently common understanding of how we got to be where we are?

In the preface to his book Africa’s Future, Darkness to Destiny (2012), Duncan Clarke says Africa’s economic drama is best understood in the context of its “continuously evolving past”, as he puts it. Among other things, this requires an appreciation of the older economic modes that still shape the rude realities of subsistence in Africa.

Aside from the utility of this sentiment, the phrase “continuously evolving past” is particularly striking. Certainly, it has proven salient to this edition of Africa in Fact.

We have interpreted Clarke’s description to include a shifting definition of what constitutes history.

The idea that history is about the core ideals that shape human life cannot be easily pinned down if our understanding of our past cannot be relied upon.

Are our opinions of the past, and therefore the social, economic and political aspirations that we develop as we forge our future, dependable?

The central paradox of African history at this time, we discovered, is that we are in fact not united by our history; our discourse as Africans almost always emphasises non- pluralism when our reality is, in fact, pluralistic and deeply nuanced.

This complex fabric of the past is further complicated by the processes of framing through our cognitive biases, our politics, our academic disciplines, among a host of other influences.

Epochs are so overwhelmingly iconic – in the case of slavery for example – that our attempts to interpret them can involve inherent biases and distortions that can easily misdirect our attempts to navigate the future. Extend that to our pre-history, our ancient civilisation, our colonial history and uhuru. Maybe we do not need to act, but rather have an understanding that we need each other’s differences.

In this edition, Terence Corrigan points out in his article that conflicting claims about the past are an intrinsic part of a plural society, and the ambiguity of Africa’s heritage must be acknowledged.

Marcel Gascón Barberá’s take on the history of communism in Africa argues that the embrace of the ideology was a pragmatic choice among emerging African elites because the Soviet Union provided support for liberation struggles that western and other powers did not – but that the pragmatic choice had poor outcomes in the authoritarianism of many liberatory regimes.

Ini Ekott argues that early post-colonial African leaders were forthright in their dealings with their western counterparts but that later generations have been less confident, hampered by their own poor record of conflict, corruption and poor governance and, more recently, by intense media scrutiny.

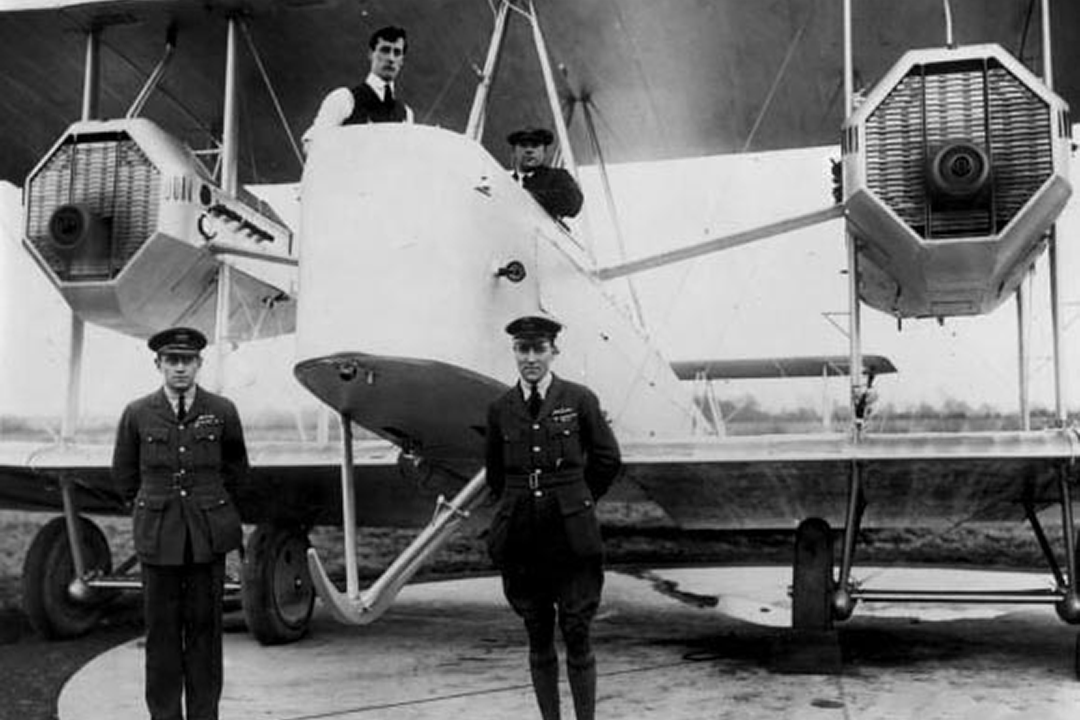

Toby Green’s article offers some surprising revelations about long-standing reciprocal diplomatic and other relations between Africa and the world in the 18th century, while Mike Moon explores the continent’s many megalithic structures, including Sudan’s pyramids, the ancient Aksumite city of Axum (in present-day Ethiopia) and Great Zimbabwe.

Richard Jurgens and Yunus Momoniat’s look at the long history of libraries in Africa reveals that the continent has been host to three great cultural traditions: Hellenism (the Alexandria library), Christianity (the monastery near Mount Sinai) and Islam (the libraries of Timbuktu.

François Misser, in reviewing Rwanda’s post-genocide history, argues that while the country’s government has established an archive, access to researchers remains limited, and that there is little will among authorities, including the UN, to allow researchers full access to important documents of the time. (In a response, the spokesman of the Secretary- General of the UN disputes this, and offers figures showing why.)

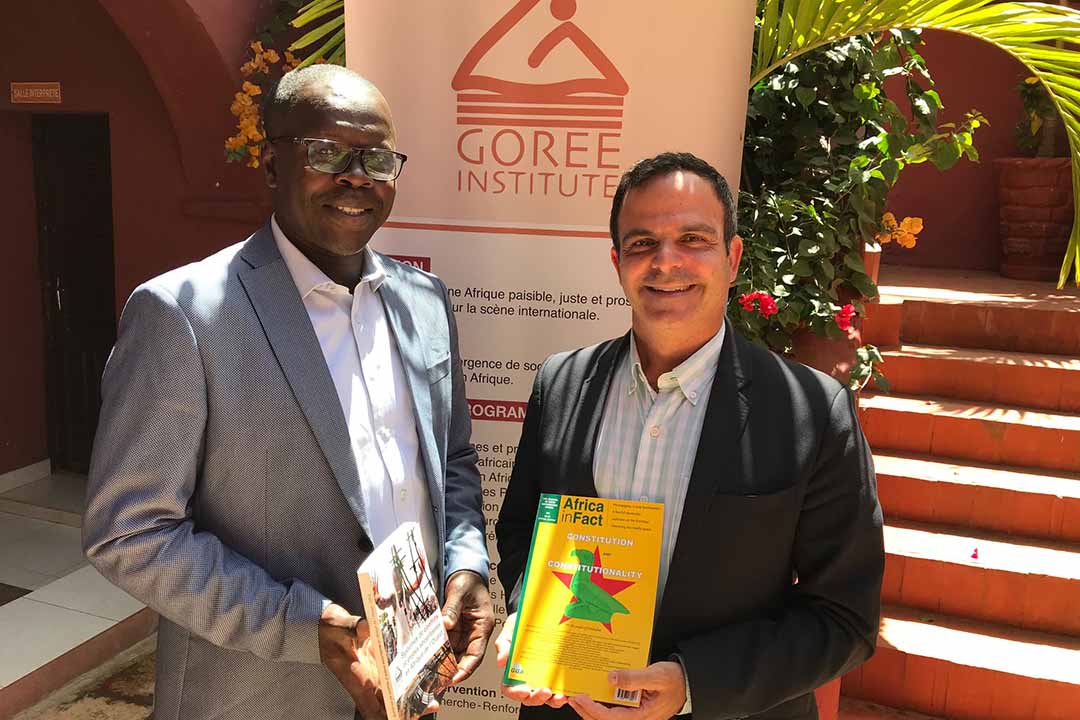

In his article, Jack Poole looks at the Mourides, an influential sect of Islam that has played an important part in the creation of the nation state of Senegal, which is officially secular, through the influence of its philosophy of the brotherhood of all Africans, regardless of ethnicity or other origins.

Blame Ekoué looks back at the colonial past of Togo, tracing it to a treaty signed between the then-king of Togoville and Germany in the late 19th century, and interviews the current king, as well as several elders who were alive during the time of the German colonisation of the country.

Lance Claasen looks at the difficulties involved in developing a school history curriculum for South African schools, given the need to reverse prejudices from the apartheid era and to make the country’s history more Afrocentric and relevant to students.

Mokete Pherudi traces the history of political assassination in the tiny mountain kingdom of Lesotho, arguing that the tactic of killing political opponents is now so standard that there is a term for it, Koeyoko, meaning “secret political elimination machinery”.

In his piece on recent Ethiopian history, Elias Gebreselassie looks at the border town of Badme, which was the scene of intense fighting between the government and Eritrean secessionists, and where the borders between the two countries remain closed, though politicians and locals are hoping that they will re-open soon.

Michael Glover explores the importance of cattle in southern Africa, and how this helped to shape cultures in pre-colonial times, and also at how colonial practices changed and disrupted some of the ways cattle were used and valued.

We present in this edition of Africa in Fact a range of subjects to represent the value pluralism, which is our lived reality on the continent.

As such it is also our contribution to a holistic, inclusive, but above all, pragmatic vision for the future of Africa.