Will South Africa’s October polls be Covid safe?

South Africa’s sixth local government elections (LGE) will occur on 27 October 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic and an impending third wave remain a clear and present danger. Because of this, the governing African National Congress (ANC) and opposition parties, including the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and United Democratic Movement (UDM), have made several calls to postpone the LGE. The Independent Electoral Commission’s (IEC) commissioner, Sy Mamabolo, said, “we cannot preclude the possibility of a postponement in the context of the uncertainty”.

People queue to undergo a Covid-19 PCR test at the North Bengal Medical College and Hospital on the outskirts of Siliguri in India, on 13 May 2021. India’s healthcare systems have been stretched to the limit. Photo: Diptendu Dutta/AFP

Nevertheless, a lot remains at stake in how we ensure that the country’s municipal elections are not only free and credible but, more importantly, safe. To this effect, the IEC has appointed former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke to “evaluate the impact of COVID-19 conditions conducive to free and fair elections” and publish a report in July on the likelihood of these conditions being fulfilled. This appointment is allowed for by Section 14(4) of the Electoral Commission Act (51 of 1996).

The scope of former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke’s report is to consider views on a range of issues from several stakeholders, including the administration of the IEC; political parties; health authorities and experts; disaster management authorities and relevant government structures, and; other stakeholders functioning in the constitution and electoral democracy environment.

As the former Deputy Chief Justice is aware, navigating this period will need a general will that cuts beyond political lines and narrow calculations and immediate commitment to the legitimacy and integrity of the country’s democracy and the wellbeing of its citizens. However, many legitimate considerations must find expression in the former Deputy Chief Justice’s report, which is of utmost importance in the short time.

Between a rock and a hard place

Within a democratic political culture, citizen participation is a crucial mechanism for strengthening good governance. In South Africa, as the closest sphere of government to the people, local government is where service delivery issues are mediated. Elections allow citizens to express their views on important issues and effectively give their representatives the mandate to serve for the next five years.

The pandemic has negatively impacted municipalities by straining cashflows, due to revenue collection shortfalls and depleting cash reserves. By effect, it has also reversed some essential gains made in respect of service delivery. On the other hand, the National State of Disaster resulted in the suspension of civic engagement and participation to limit the spread of the virus by minimising interactions between people in line with health protocols. For example, for South Africans, it meant that consultative integrated planning processes, meetings, exercising the right to demonstrate through protest and assemble in political gatherings such as rallies, were curtailed. Despite this, there might be more harm done than good from holding elections in late October. Several risks are worth considering. Moreover, some lessons can be learned from India’s approach to holding elections in these uncertain COVID-19 times.

India’s COVID-19 reckoning

At the World Economic Forum in January 2021, India’s Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi, in reference to the COVID-19 pandemic, confidently announced that the country had saved itself from “a big disaster”. Following his speech, India’s government began to ease COVID-19 restrictions. With the government’s support, the world’s largest religious Hindu festival, Kumbh Mela, saw an estimated 9 million people congregate on the Ganges River without proper social distancing measures or mask-wearing in place. Likewise, leading up to India’s local elections, large political rallies were held without proper COVID-19 protocols. Healthcare experts warned against allowing the festival and other large gatherings to go ahead. These events fuelled what would be a catastrophic set of events, with a disastrous impact on the country. The surge of infections would also cost the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) party a win in West Bengal, a critical state with nearly 100 million people. After the devastation that unfolded, PM Modi’s words have come back to haunt him.

The extent of impact and status of vaccinations

Leading up to the infection spike, India was administering vaccines, but supply began to decline, causing a vaccine shortage in some of the most populous states. The decline in vaccine supply was partly due to a fire at a facility in January, coupled with massive demand. Home to the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer, the Serum Institute of India (SII), the country manufactures Covishield (a version of AstraZeneca). At the start of February, the SII entered into a long-term supply agreement with the global vaccine equity scheme known as COVAX. Once the second wave hit, the government imposed a ban on vaccine exports. The SII was set to deliver its 170th million dose in May 2021 but is currently only at 65 million doses. Shortfall numbers are based on delays related to shipments from the SII only. There is currently no timetable to resolve SII-related delays.

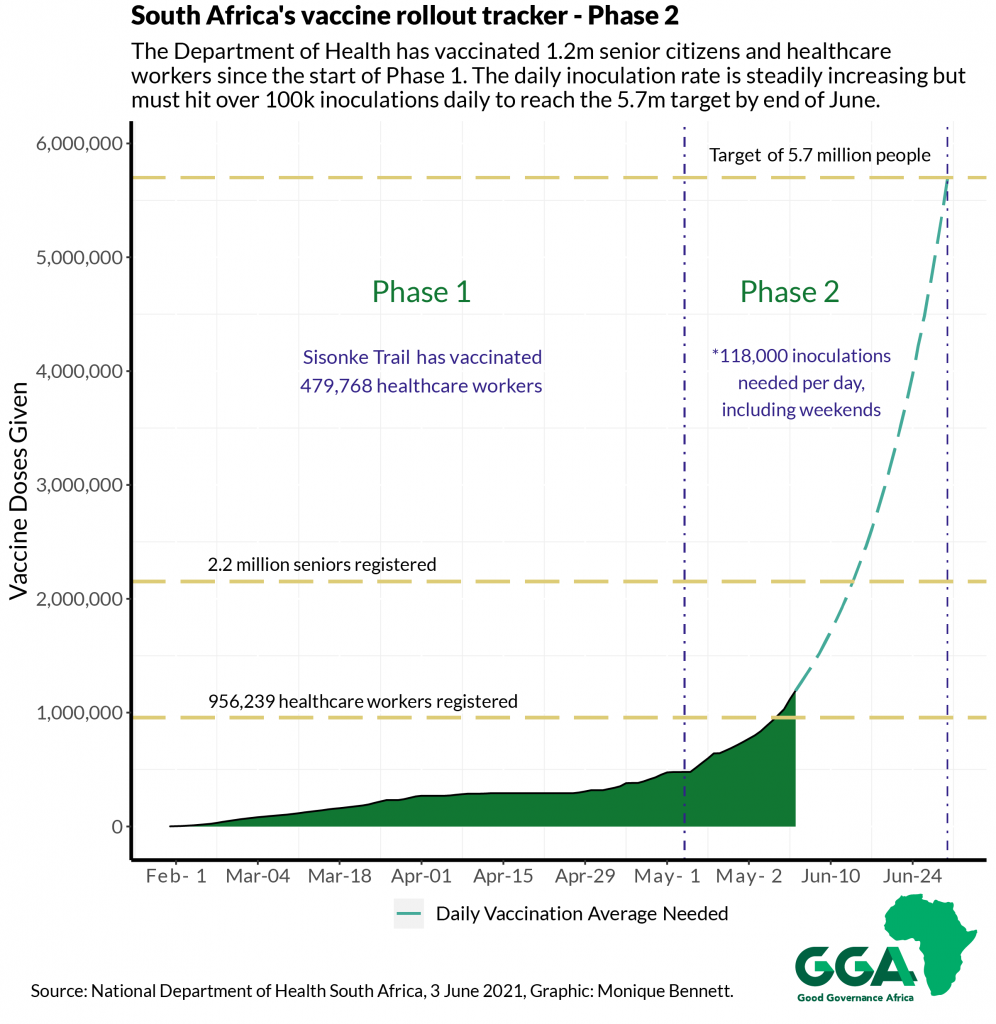

Similar to India, South Africa’s healthcare system has been stretched to the limit during the first and second waves. There was evident strain with the lack of facilities, overcrowding, and oxygen and medical personnel shortages throughout the pandemic’s trajectory. This is a consequence of governance failure to make adequate investments into proper primary level public healthcare. Equally important is the formulation of policies to devise long-term solutions to control conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, so as to avoid economic interventions to curb the spread and severity of the COVID-19 virus. Two weeks ago, it was reported that the B.1.617 variant identified in India shares the same mutation found in B.1.351 (identified in South Africa), but is possibly 20% more transmissible. Experts are concerned that it may be relatively resistant to the antibody induced by the COVID-19 vaccines. South Africa is experiencing a spike in positive cases, and predictions indicate that the country could witness a peak in infections between July and October. This, coupled with the slow rate of vaccinations, could make holding physical local elections challenging.

Summary of key lessons from India’s election:

- Preemptive warnings were issued by India’s electoral commission and scientific advisors, which asserted that large public gatherings coupled with a new variant of concern (identified in early March) could cause a second wave of infections. Political parties ignored these warnings as large rallies took place without strict COVID-19 public health protocols.

- Election training venues for government staff did not follow proper COVID-19 health protocols, resulting in crowded venues without any social distancing. To aggravate the situation, some staff were called to the venues despite being in the high-risk COVID group due to their age and comorbidities.

- Ensure that hospitals have a sufficient supply of medical oxygen to mitigate large hospital admissions and prevent the unnecessary loss of life.

- Despite India being a vaccine manufacturer, over-reliance on local manufacturing led to a vaccine supply squeeze. The government should consider a diverse vaccine supply procurement strategy to mitigate against shortages of vaccine supplies.

Best practices from elections held during the COVID-19 pandemic

Countries that held elections during the height of the pandemic were forced to adapt and innovate their electoral processes. Elections are inherently social gatherings that encourage communities to participate and engage with their chosen officials and fellow voters. Key innovations installed for elections across the African continent and other parts of the world include:

- Instead of in-person meetings, the Malawi government undertook a series of virtual engagements with key stakeholders in preparation for the election.

- Using social media to distribute COVID-19-sensitive voter education material in Malawi, the United States and Serbia.

- Temperature checks and sanitising done before casting votes in South Korea; those with a fever could vote in separate areas.

- Disinfecting frequently used surfaces and ensuring venues are ventilated was key in Poland and the Dominican Republic.

- During the French election, voters were encouraged to use personal stationery items to avoid touching shared materials.

- Voting hours were staggered in Singapore within two-hour slots, while some countries increased the number of polling stations and extended voting hours.

Recommendations for South Africa’s upcoming Local Government Elections

Below are some recommendations that the former Deputy Chief Justice’s report and other crucial role players should consider so as to avoid an India-type situation in South Africa:

The IEC

The IEC has publicised a list of guidelines to ensure voter safety for elections during COVID-19. They include minimum protocols such as the wearing of masks, sanitising, and social distancing. As a litmus test, the IEC successfully conducted by-elections in November and December last year and on 21 April and 19 May this year under alert level one of the restrictions. Over two weeks ago, the last cycle comprised 40 bi-elections across 25 municipalities in six provinces, including the Free State, Gauteng, Eastern Cape, KwaZulu Natal, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga. This was perhaps the only opportunity to test the state of readiness regarding electoral protocols and processes and the maintenance of COVID-19 safety measures. Although there were no reported incidences of non-compliance that cast doubt on the process, it is worth mentioning how delivering nationwide elections will be a challenge, given the different scales regarding geographic scope and volume.

- The IEC should increase the opportunity for special votes by giving more predetermined dates before the elections. These are typically granted to sections of the population that cannot vote on election day, such as the elderly, healthcare workers, law enforcement and electoral officials. The scaling up of this process, and the inclusion of people with comorbidities, will help minimise the number of people who physically go to voting stations, thereby mitigating the risks.

- For these Covid specific circumstances, the efficiency and capacity of the IEC must be improved through adequate funding for the institution and better training of electoral officials; this must extend even beyond this period.

- As an opportunity, it would be worthwhile to start the conversation around institutionalising hybrid approaches, to voting that make use of e-voting, the mailing of ballots via post, and other approaches that are orientated towards mitigating the impact of the risks of the future on elections.

Political parties and the use of alternative platforms for campaigning

- Active engagements with relevant organs of state and political parties to address compliance and adherence to protocols.

- Limit the scale of political rallies and the mobilisation of large crowds and door-to-door activities by parties to prevent possibilities for super-spreading.

- As an alternative, the use of social media platforms is a viable platform. For example, parties can opt to use Facebook Live, YouTube and WhatsApp, or even traditional mediums like radio to broadcast manifestos and communicate with their electorate.

- Leveraging technology can help to prevent voters from feeling like they are unable to participate in the election run-up.

- Similarly, as in the past, the engagements between the leaders of political parties represented in the national and provincial political party liaison committees and the IEC should be strengthened, occur more regularly, and continue to monitor the situation in the next few weeks.

Actions required from health authorities and citizens

- There should be a sufficient level of information sharing by the Ministry of Health on the latest epidemiological data trends and rate of vaccinations in good faith. Continuing with and improving this process will ensure that people are not merely in a state of fear and panic, but are given the sense of agency to make informed decisions.

- The most significant capacity constraints in the health service must be declared and hopefully resolved. Moreover, the vaccination process must be sped up and citizen buy-in improved, which would create enabling conditions for the elections to occur with less risk.

- Responsible citizen behaviour will be crucial for the success of the elections. The onus is on the citizens to value their democratic right and adhere to the rules.

If the critical concerns against holding elections continue and Moseneke expresses his reservations, delaying the elections is a possibility that must be explored. The only legitimate way to delay the elections would be to change chapter 7, clause 59 of the South African Constitution, as agreed upon by a two-thirds majority vote in parliament. If all or most of these realities are not factored in, and the safety requirements are not met, South Africa might have its reckoning, like India.