Ifrah Ahmed

At 17, Ifrah Ahmed arrived in Dublin, Ireland in 2006, escaping war in Somalia. To support her asylum application, she had to undergo a medical check-up, which included a Pap smear. The medical personnel were shocked to discover she had undergone female genital mutilation (FGM) and Ahmed was surprised that they were shocked. Living in Somalia, Ahmed, who underwent FGM at eight, assumed every girl in the world underwent the procedure.

“I remember how all the doctors came together asking each other what happened to me,” Ahmed told Africa in Fact. “To us it was normal. But seeing all these women asking why and how. It was not easy. It was painful and emotional.”

FGM is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or another injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

Ahmed said when she discovered the procedure was not the norm, she decided to fight against FGM to prevent girls, especially from the migrant community, from going through what she did. Since then, as an activist, Ahmed contributed to the campaign that led to the criminalisation of FGM in Ireland in 2012.

“I wanted them to be free to talk about how their genitalia had been cut and sewn,” said Ahmed, adding that she had faced a backlash from her community, which accused her of being westernised.

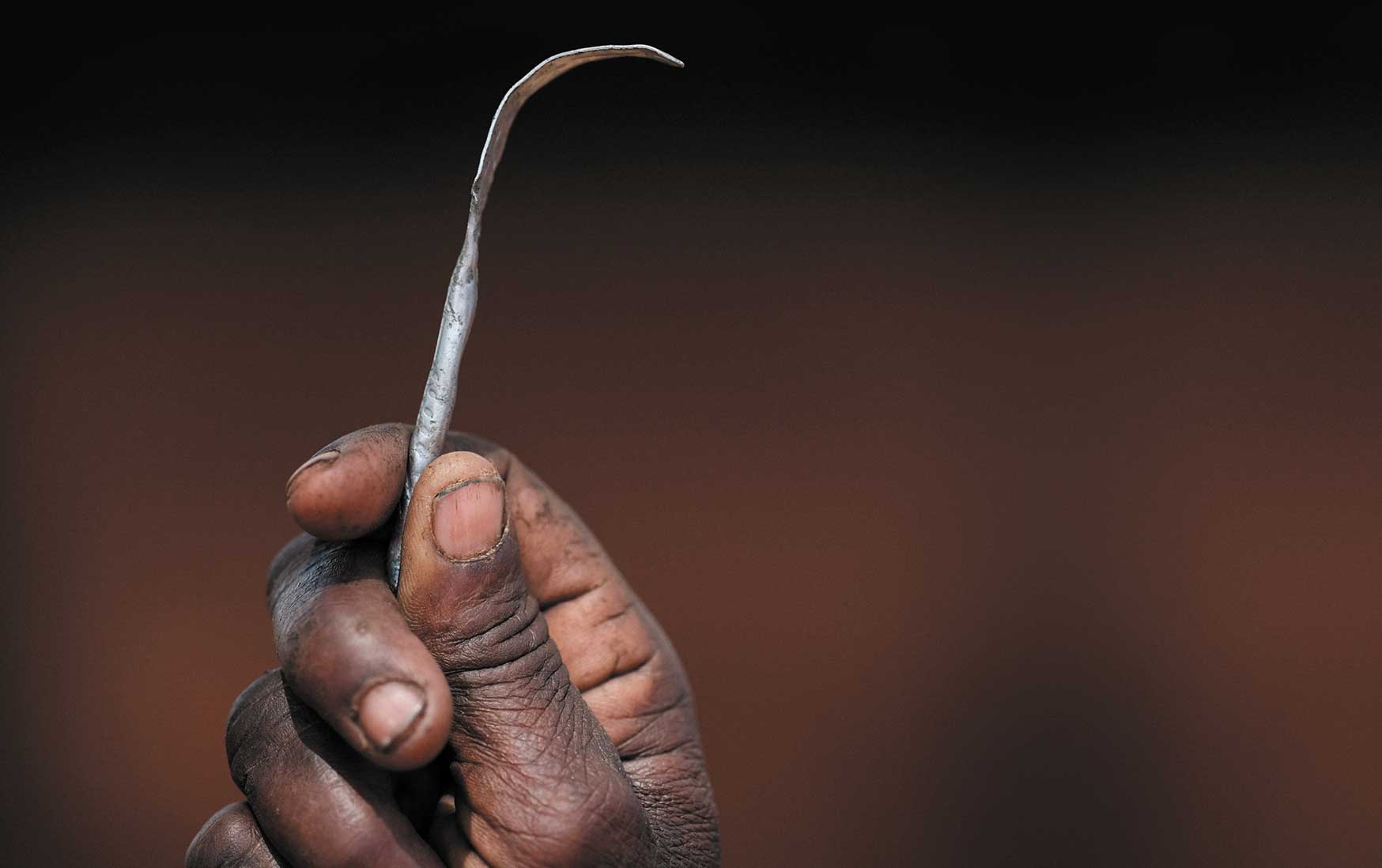

Former genital mutilation (FGM) cutter Monika Cheptilak, who stopped practising after the country passed an anti-FGM law in 2010, shows a homemade tool made from a nail used for FGM, during a meeting of an anti-FGM women’s group in Alakas village, bordering with Kenya, north-east Uganda in January 2018.

Ahmed, the mother of a two-year-old girl, has founded two non-profit organisations, including one named after her. She has also worked with the United Nations (UN) and other agencies. The Ifrah Foundation is registered in Ireland and Somalia, a country that still has the highest proportion of FGM in the world. According to data from the UN, 99% of women aged between 15 and 49 in Somalia have gone through FGM.

Ahmed has also worked with the Somali government in different roles, including as a gender advisor in 2016. Her foundation works with local organisations and runs a campaign called Dear Daughter, whereby mothers pledge to their daughters that they will not have to undergo FGM. She is frustrated that in Somalia, a Bill to ban FGM has not been passed yet, but acknowledges there has been progress, particularly in getting people, including men and religious leaders, to start speaking against the practice.

WHO has identified four types of FGM, all of which carry health risks for women and girls. FGM can cause severe bleeding and problems urinating, and later cysts, infections, as well as complications in childbirth and an added risk of newborn deaths, according to WHO, which estimates the cost of healthcare for women living with conditions caused by FGM to be $1.4 billion annually.

Nimco Ali, originally from Somaliland, is one of the women that have gone through reconstructive surgery, following FGM. “I had surgery at age 11 to deal with near kidney failure, which happened because of FGM. The psychological consequences are lifelong though – as are severe medical consequences such as maternity and urinary issues – and girls die too from FGM,” said Ali.

Nimco Ali

Ali, now based in the United Kingdom, is the CEO of the Five Foundation, which is fighting to end FGM in Somaliland and other countries. In Somaliland, FGM remains legal and 98% of women have undergone the procedure. In September, Ali and her colleagues met with Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi and other leaders to engage them in the fight against FGM.

“We will win this fight. The Five Foundation has made major progress on prioritising and leveraging new funding for the issue. We have the aim of ending it by 2030,” said Ali.

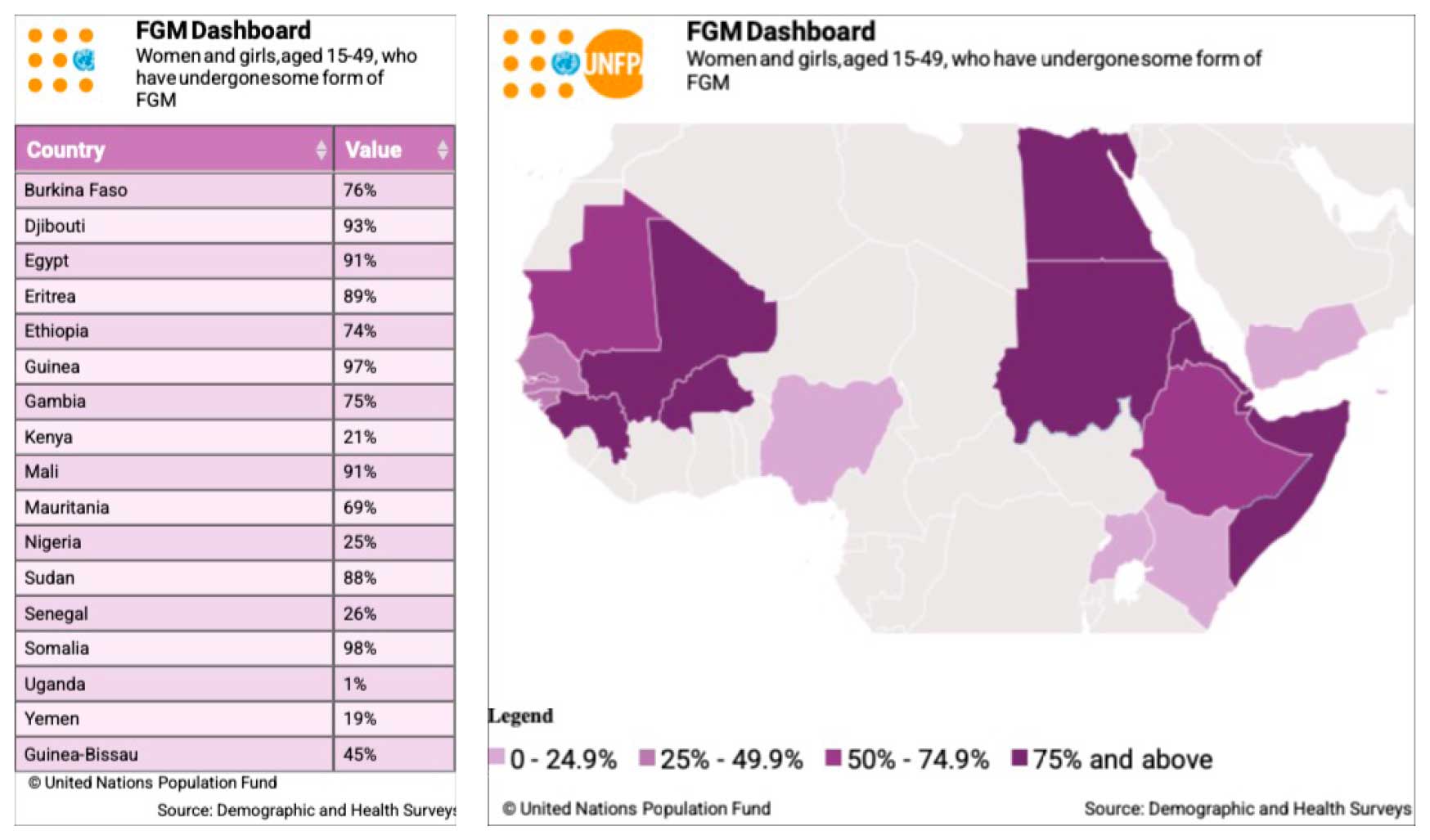

Two UN agencies, the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), lead the world’s largest programme aimed at ending FGM. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5.3 sets 2030 as the year to end FGM. With eight years to go, the organisations noted in a recent progress report that “globally girls today are 33% less likely to undergo FGM than 30 years ago. Despite this gain, challenges abound as the relative progress recorded has been uneven across countries”.

Out of the 91 countries where FGM is documented, 33 are in Africa, according to UNFPA. Over 125 million girls and women have undergone FGM, accounting for more than 60% p of the global number – 200 million.

Some countries have made progress towards ending FGM and others have not, according to an April 2022 report from the AU. Benin, Nigeria, Liberia, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Central African Republic, and Egypt registered a significant decline in prevalence, signifying a possible generational shift, where younger women are less likely to undergo FGM compared to older women. Cote d’Ivoire, Mauritania, and Sudan had a slight decline in prevalence, signifying limited success in convincing community members to abandon the practice en masse. Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, Mali, Guinea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Chad had no significant change in prevalence, indicating that interventions were lacking or had failed.

UN data shows that FGM among girls from birth to 14 is lower than among women aged 15 to 49 in most countries. In Somalia, while the prevalence rate among girls and women aged 15 to 49 is 99%, 27% of girls aged from birth to 14 have gone through FGM. However, in countries like Mali (73%), the prevalence rate remains high among girls aged from birth to 14.

In some countries, which have lower national prevalence rates, there are areas where most women have gone through FGM. In Uganda, one out of every 100 women nationally has undergone FGM, which the country banned in 2010. Yet in the Pokot community, in the Amudat district, as many as 95 out of every 100 women have undergone FGM. A local non-profit organisation, Communication for Development Foundation Uganda (CDFU), is leading the fight against FGM in the community, with support from UN Women.

Among CDFU’s community activists is Priscilla Nangiro, a former FGM practitioner. Having learned about the dangers of FGM from CDFU, Nangiro gave up practising and now campaigns against FGM in the same community where she used to practice.

She underwent FGM at eight, thinking it was necessary to transition into adulthood, improve her chances of getting married and earning her parent’s dowry, and “fit into a community that does not allow uncircumcised people to interact, sit or even share a meal with those who are uncircumcised.” Nangiro says she bled for the whole day after undergoing FGM and struggled during sex and childbirth.

“Having sex with my husband was very painful because the wound burst. Sex was not enjoyable for me. I had difficulties in giving birth to all six of my children … they had to cut me again,” she told Africa in Fact.

Left: Former FGM practitioner Chepchai Limaa poses in the abandoned cave where girls used to heal after their circumcision, at their spiritual site near Katabok village, northeast Uganda, in January 2018. Uganda banned FGM in 2010.

Right: Former FGM practitioner Priscilla Nangiro.

Nangiro is not the only traditional practitioner abandoning the tools used to cut and sew innocent girls. In Nigeria, which has the third highest number of girls and women who have undergone FGM by virtue of its population size, a former traditional practitioner, Charity Aforkwalam, has also stopped the practice and joined the fight to end FGM, according to a July report in the Premium Times.

But some parents determined to have their girls undergo FGM are avoiding traditional practitioners and opting instead for a medical procedure. According to recent UNFPA estimates, around one in four girls and women between the ages of 15 and 49 who have undergone FGM, or 52 million, were cut by health workers, something that has been condemned by the WHO, the AU and activists.

“The medicalisation of FGM is extremely harmful and is growing in places like Egypt and Kenya,” Ali says. “Any health professional needs to abide by the principle of Do No Harm. It is outrageous that they carry out FGM. They should be arrested. There is no such thing as a safe way of performing this awful violation of a girl’s rights.”

The fight against FGM also faced a setback with Covid-19. Activists and organisations were unable to continue campaigning and some funding was diverted to fight the pandemic. With only eight years left to make the UN deadline to end FGM by 2030, Ahmed says activists, leaders, civil society, the AU, and the UN must unite and combine their efforts. African leaders, she added, must not leave the fight to activists, civil society, and international organisations.

“We need our African leaders to intervene and speak about FGM. Some fear losing popularity at elections, but they have a role to play, and they must play it,” she said. “We must demand accountability from our leaders. It’s their job to protect people and women’s rights.

“In 2030 I don’t want to only celebrate my daughter’s 10th birthday – I also want to celebrate the legacy of ending FGM globally.”