Its heyday as Africa’s musical epicentre may be over, but Kinshasa’s music scene is anything but dead

Dripping with sweat, I put my guitar down and hurry to join our singer at the front of the stage for the dance routine. Our rhythm section glides into another 15-minute percussion break. The entire crowd is on its feet, repeating our steps. Oversized bottles of Primus, Tembo and other local beers line the tables, while an ntaba (goat) grill in the corner is spewing smoke over everyone. We’ve been playing for three hours already and it’s only just getting started. A marathon night awaits.

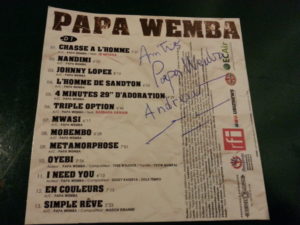

My band, Capitaine Tokoss & l’Orchestre Kinsonique, is playing at Freebox, a dingy, unassuming bar crammed awkwardly into a triangular patch of land adjoining Rondpoint Forescom, a roundabout in the downtown Gombe district of Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). It’s June 2017 and we’re halfway through our tour of the Kinshasa bar circuit. This gig has a special resonance for me: I’m finally playing on the same stage where, on my second night in the Congolese capital in June 2014, I saw Papa Wemba, the “king of rumba,” launch Maitre d’Ecole, his last-ever album.

Jean Goubald (vocals, centre left) makes a special guest appearance at Moli Mokelenge (vocals and guitar, centre right) concert at Guez Arena, Kinshasa, 26 August 2016. Rest of the lineup: Yves Karim Ntumba (bass guitar), Paulin Lukombo (drums) and Shaddai Kadi (congas) Photo: Andrew Panton

Musicians in today’s scene live in the shadows of the glory days that Papa Wemba once knew. Kinshasa was the birthplace of the Congolese rumba and soukous (from the French secouer, “to shake”) that dominated the continent in the second half of the 20th century; the home to Zaiko Langa Langa, the seminal group, which Papa Wemba joined in the late 1960s before forming his spin-off, Viva La Musica, in 1977.

Back then Kinshasa was the “Rumble in the Jungle” city, which hosted James Brown, BB King and other big names in Afro-American music at the Zaire 1974 festival. The intervening years of conflict, instability and economic ruin have relegated it to playing second string on the continent, while Nigerian, Ivorian and Angolan beats have invaded the city’s bars and nightclubs.

But the kinois (residents of Kinshasa) have not lost their taste for ambiance. Music provides an escape from life in a lawless, jobless city where survival means resorting to Système D: hustling and struggling on, relying on one’s guile, grit and resourcefulness (débrouillardise in French; hence the “D”). The population is growing rapidly, being projected to double to over 24 million by 2030, according to a 2018 World Bank study of urbanisation in the DRC – but living conditions are not keeping apace.

The city’s unforgiving disparity continues to test, inspire and provoke its artists, propelling them to greater heights of expression and creativity. Some of the creative talents finding new ways to revolt against the absurdity of life in Kinshasa are the subject of an upcoming film by La Belle Kinoise, the production outfit of French film-making duo Renaud Barret and Florent de la Tullaye.

The city’s unforgiving disparity continues to test, inspire and provoke its artists, propelling them to greater heights of expression and creativity. Some of the creative talents finding new ways to revolt against the absurdity of life in Kinshasa are the subject of an upcoming film by La Belle Kinoise, the production outfit of French film-making duo Renaud Barret and Florent de la Tullaye.

Due for release in 2019, Système K (the “D” being replaced by the “K” for Kinshasa) features Kokoko!, a musical collaboration pairing French DJ and producer Xavier Thomas (alias débruit) with a collective of Congolese musicians whose upcycled plastic bottle xylophones, milk-powder tin guitars and drums made from old toasters give a new musical voice to items resurrected from the gutters of kin la poubelle – the trash-can city. They describe their music as “the soundtrack of Kinshasa’s tomorrow”. The style is raw, industrial, pulsating and unapologetic, mimicking the clamorous noises of the streets.

Kokoko! is the latest in a line of musical acts that La Belle Kinoise has uncovered over 15 years of exploring the underbelly of Kinshasa’s alternative scene. Other names they’ve worked with include Jupiter & Okwess International, Staff Benda Bilili and Mbongwana Star, a self-described “trans-global, barrier-busting sound machine”. However, although they’ve gained a large following in Europe, these artists neither attract, nor seek out, mass appeal at home.

Papa Wemba Photo: Radio Okapi.

The mainstream, meanwhile, is experiencing an identity crisis. Kinshasa’s musicians and ambianceurs often proudly point out the influence of their country’s music on their West African colleagues, but the reverse is increasingly true. Take, for example, Fally Ipupa, who claimed to introduce a new style of music with his last album, Tokooos, which features Nigerian star Wizkid and has a distinctly naija feel. Or take Koffi Olomide and Ferre Gola, who, although sticking to failsafe Congolese formulae in their latest releases, have both recorded with J. Martins, another big Nigerian name.

This sort of reinvention is not new to the Kinshasa scene. Congolese rumba was born in the 1940s when Afro-Cuban styles arrived (or, perhaps, returned) from the Caribbean and mixed with traditional Congolese sounds. Soukous, rumba’s up-tempo offspring, emerged with the ascendancy of electronic instruments. Its two-part song structure, culminating in the extended seben(e) dance section, was introduced later in the 1970s. As the cassette tape, the new technology of the day, transformed their works into piracy-prone commodities, musicians now realised it was the thrill of dancing that would keep punters coming to live shows in spite of the worsening economy.

Today’s technology gives Congolese musicians greater access to mainstream audiences, both at home and abroad. The telecoms companies promote upcoming talent – among them, Gaz Mawete (Vodacom) and Innoss’B (Africell) – as part of a drive to stay connected to their younger, smartphone-owning customer segments. A new generation of beatmakers reinterpreting Congolese rhythms with electronic sounds is emerging thanks to increasingly available (but often pirated) digital music technology and the viral power of YouTube and social media.

Local start-ups Baziks and Kivusik have created home-grown music apps, albeit without the reach or firepower of Google’s offering. The launch, in April 2018, of Trace Kitoko, a channel dedicated to Congolese music and arts on Trace Group’s TV and streaming services, was a firm signal of confidence that the DRC’s “incredible music force” – as the company’s website describes it – still has the power to capture and captivate audiences across the continent.

For a showpiece demonstration of this force, look no further than Bakolo Music International. Convened by the late Wendo Kolosoy, they were part of the so-called “first generation” of musicians that created and popularised Congolese rumba in the 1940s. Bakolo, aptly, means “pioneers”. The group of near-octogenarians has reformed, recruiting an upcoming young star, Jocelyn Balu, to join them in Wendo’s absence. They are currently on a tour of Europe and have begun work on a new album (due for release in early 2019) containing a mix of new compositions and old classics, including the timeless Marie-Louise.

Rodriguez Vangama and Les Salopards performing at Guezarena, 2016 Photo: Andrew Panton

The Bakolo exemplify the character traits that, to my mind, define the Kinshasa scene: solidarity, camaraderie, resilience, and, of course, astonishing talent and creativity. Music in Kinshasa is a shared enterprise, a layered tapestry, which each generation contributes to, reinterprets and reinvents. That shared enterprise embodies the social fabric of the city, woven and embroidered by migrants from all corners and ethnicities of the country.

When Papa Wemba died in April 2016, nearly two years after I saw him play at Freebox, impromptu memorial concerts and parties were organised in almost every quartier (neighbourhood) of Kinshasa during three days of national mourning, as a fervour of shared loss swept over the entire city. It was an inspiring affirmation of the unifying power of music and its role in keeping this patchwork metropolis from coming apart at the seams. Perhaps more than any other city, it’s Kinshasa that makes the musicians, and it’s the musicians who make Kinshasa.