A giant Chinese shoe manufacturer is lacing up for the long run. Will others follow in its footsteps?

Treading a new path

By Elissa Jobson

At 6.45am the first bus halts outside the main gates of the Eastern Industry Zone. The doors clang open. Bleary-eyed young men and women begin to emerge and brace against the chill morning air.

A second, then a third and fourth bus arrives from the nearby dormitories, disgorging more and more workers dressed in the turquoise polo shirts that employees are required to wear on the shop floor at Huajian, one of China’s largest footwear manufacturers. Each member of staff pauses briefly at the factory door and presses an identity tag against the electronic sensor that records their clocking-in time.

Minutes later small groups of employees begin to assemble inside and outside the main buildings. Lines are formed, calisthenic drills executed and chants recited before workers march briskly to their stations and begin their duties.

hese scenes, played out in thousands of factories across China each day, seem more than a little incongruous here in Dukem, about 40km south of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. But they could become an increasingly familiar sight if, as the Ethiopian government hopes, Chinese companies move more light manufacturing operations to this booming east African country.

Boys work as tailors in a shop at the market in the city of Humera, in the northern Tigray Region. EDUARDO SOTERAS / AF

“With the fast growth of its economy, Ethiopia will become a promising land full of trade and investment opportunities,” wrote Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn at the first Africa-China Commodities, Technology and Service Expo, held in Addis Ababa in December 2013. “More Chinese enterprises will be attracted to Ethiopia with technology and investment, which will achieve win-win cooperation.”

Chinese manufacturers, facing rising costs at home, are well aware of Ethiopia’s advantages: cheap labour and land leases; low-cost and reliable electricity in Addis Ababa, where most manufacturing is sited (with more to come soon as a series of hydroelectric dams turns the country into an exporter of electricity); easy access to cotton, leather, and other agricultural products; and proximity to key markets in Europe and America.

This explains why Addis Ababa was chosen as the location for this fair, the first of its kind to be held on the continent to showcase Chinese companies and generate business. “We selected Ethiopia as the destination of this expo because we think Ethiopia is a place many Chinese industries would like to relocate to,” said Gao Hucheng, China’s minister of commerce. Huajian, which produces shoes for Guess, Tommy Hilfiger, Naturalizer, and other Western brands at its Dukem factory, is keen to take full advantage of the opportunities Ethiopia affords.

A worker operates a sewing machine at a shoe factory belonging to the Mohan Group in the area of Gelan, Ethiopia, on December 31, 2019. The factory was hit hard by electricity cuts during the latest round of power rationing in Addis Ababa in May and June 2019. Ethiopian business leaders hope the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam will alleviate the country’s electricity problems. EDUARDO SOTERAS / AFP

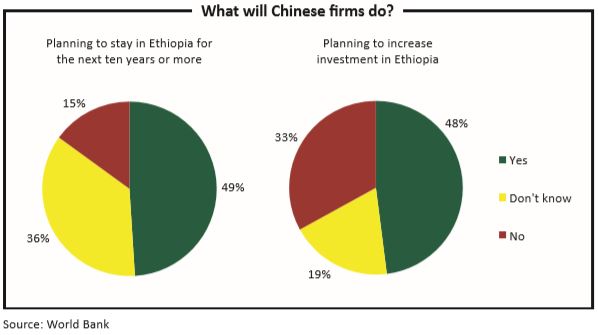

“We are not coming all the way here just to reduce by 10%-20% our costs,” insists Helen Hai, former vice-president of Huajian Group, who is now advising the Ethiopian government on how to attract Chinese investors. “Huajian’s aim here is in ten years’ time to have a new cluster of shoemaking. We want to build a whole supply chain,” she adds.

The company’s vision is bold. Huajian began producing shoes in Ethiopia in January 2012 and the company now employs 2,500 people in the country, 90% of whom are local. Huajian currently exports more than $1m worth of shoes from Ethiopia to Europe and the US each month.

But within a decade, Huajian hopes Ethiopia will become a global footwear industry hub, providing jobs to more than 100,000 local workers, 30,000 of whom will be directly employed by Huajian.

Together with the China-Africa Development Fund, a private-equity facility, Huajian has committed to invest $2 billion over the next ten years to create a “shoe city” that will provide accommodation for as many as 200,000 people, as well as factory space for other footwear, handbags, accessories and components producers. Ms Hai is convinced Ethiopia will become “the future manufacturing floor of the world”.

She believes it should follow China’s path and begin with labour-intensive industries such as footwear and garment production. “The labour cost in shoemaking in China is about 22% of the overall cost portfolio,” she explains. “In China today the cost of each labourer is $500 [a month]. In Ethiopia it is only $50. So the question comes down to the efficiency.”

If one Ethiopian worker can produce the same number of shoes as one Chinese worker then labour costs could be reduced from 22% to 2.7% of the new total cost. People argue that African efficiency is low, Ms Hai says, but she maintains that with one year’s training Ethiopian workers could achieve “70% of the efficiency” of workers in China.

The profit motive for relocation to Ethiopia is clear. But other factors—excise breaks, tax holidays and cheap land rental offered to investors in certain preferred sectors—make Ethiopia attractive too, Ms Hai claims.

For example, Ethiopia is eligible for schemes like the US’s African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and the EU’s Everything but Arms (EBA) treaty, which allows exporters from many African countries duty- and quotafree access to America and Europe.

What is in it for Ethiopia? While the Chinese are taking advantage of Ethiopia’s cheap labour, “they bring technology, know-how and training”, Ms Hai says. “This will help the country create jobs and bring exports. That is truly the root of industrialisation.”

Grand plans like Huajian’s, however, are few and far between. Annual levels of Chinese investment in Ethiopia are low, totalling about $200m in 2013, according to the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Addis Ababa. This marks a substantial increase from virtually nothing in 2004 and $58.5m in 2010.

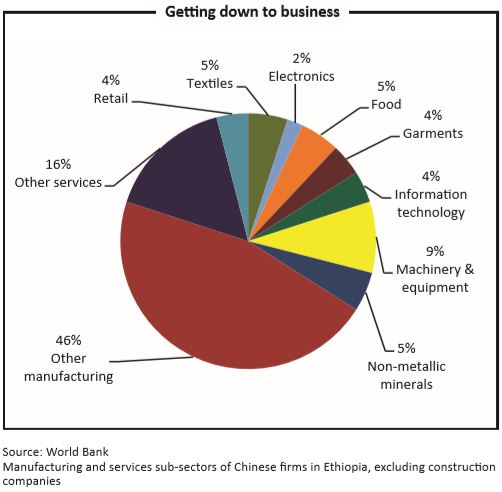

But just $50m of the current investments are in manufacturing, mainly in small and medium enterprises producing steel, cement, glass, PVC, paper, furniture, mattresses, blankets, shoes and other products. Instead, Chinese economic activity in Ethiopia tends to be focused on major infrastructure programmes—roads, railways, telecommunications and electricity transmission—which the Ethiopian government pays for with financial backing from Chinese institutions.

“This is substantial activity, at least in terms of the value of these projects,” explains Jan Mikkelsen, IMF resident representative in Ethiopia. Last December’s ChinaAfrica Expo reflected this pattern with few of the more than 130 Chinese companies exhibiting looking to open factories in Ethiopia or elsewhere on the continent.

Instead, many, like China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC), with their large, prominent stand, were hoping to secure lucrative government contracts.

“Ethiopia is a very big potential market,” says Jin Chunsheng, CMEC vice president. “There is the five year [Growth and] Transformation Plan and we expect to see a lot of power and infrastructure business which is related to the work of our company.” CMEC is currently negotiating to build fertiliser plants with Metals and Engineering Corporation, a major state-owned Ethiopian enterprise, Mr Jin adds.

Although manufacturing in Ethiopia is beginning to rise, it accounted for only 12% of GDP in 2012-13, compared to 43% for agriculture and 45% for services, according to government figures. The sector’s annual growth, however, was 18.5%, as opposed to 7.1% and 9.9% respectively for agriculture and services. Yangfan Motors, a subsidiary of Chinese automobile manufacturer Lifan, was one of a small number of exhibitors currently operating in Ethiopia.

The company opened a car assembly plant in Addis Ababa in 2009. “We chose Ethiopia because it is secure and stable,” says Liu Jiang, Yangfan’s general manager. “Furthermore the two governments [Ethiopia’s and China’s] have a good relationship and we think that this is a very important point too.” Unlike many Western countries, China has a policy of non-interference in domestic affairs, which has been appealing to African countries.

Ethiopia’s adherence to China’s developmental state model shows that the two countries share a strong affinity. Not surprisingly, business has been difficult for Yangfan. More than 83% of Ethiopia’s population live off subsistence farming in rural areas, according to the World Bank, and 90% of all car sales are used models.

The company currently manufactures around 3,000 vehicles annually but only manages to sell one-third to the local market. Lifan had hoped to use its Ethiopian base as a regional hub, but so far has been unable to distribute abroad because Ethiopia is a landlocked country with high taxes and transport costs, Mr Liu says. “To transport one container from China to Ethiopia is almost triple the cost of sending a container from China to Brazil,” Mr Liu adds.

A container from Shanghai, China, travels 12,400km to the port of Djibouti, at a cost of about $4,000, and is then transported overland 865km to Addis Ababa, for another $4,000, Ms Hai says. A 2012 World Bank study on Chinese foreign direct investment showed that investors cited customs and trade regulations and tax administration as major constraints on their business.

An underdeveloped financial sector and a dysfunctional foreign exchange market are other business impediments, Mr Mikkelsen says. In the bank’s 2014 “Doing Business” report, Ethiopia slipped down one place to 125th and dropped from 162nd to 166th in terms of ease of starting a business. Companies seeking short-term profits may not take the risk or feel that the inconveniences are worth staying the distance, says Lars Moller, lead economist at the World Bank’s Addis Ababa office.

Yangfan, however, is committed to the long haul, Mr Liu says. Later this year, the company will move to a bigger factory in the same industrial complex as Huajian. Government environmental policies will begin to favour newer, less-polluting vehicles and the ongoing road and railway construction will significantly reduce transportation costs, he adds. “In 2014 we are planning to bring two new models, one of which is especially designed for the Ethiopian market.”

Ethiopia clearly has a long way to go on its path to an industrial economy that offers jobs to its people and sensible opportunities to foreign and regional investors. Much shoe leather will be worn out before that destination is reached. Ventures such as Huajian’s and Yangfan’s offer tentative hope.

Elissa Jobson is a freelance journalist based in Ethiopia. She is the Addis Ababa correspondent for The Africa Report and Business Day and also writes for the Guardian. Ms Jobson was previously the editor of Global: The International Briefing