A picture shows electric wires connected above roofs in a district of Abidjan on June 1, 2019. Sia KAMBOU / AFP

Is Africa ready for the future? Is the continent ready to tackle the technological disruption and challenges of a rapidly changing world? Importantly, are its young people ready to take up the mantle of change?

Africa’s youth have moved from relative obscurity in political deliberations to centre stage in continental forums and conferences from Cape to Cairo. This new focus stems from concerns about how to educate and employ the millions of young people in Africa and so improve their livelihoods.

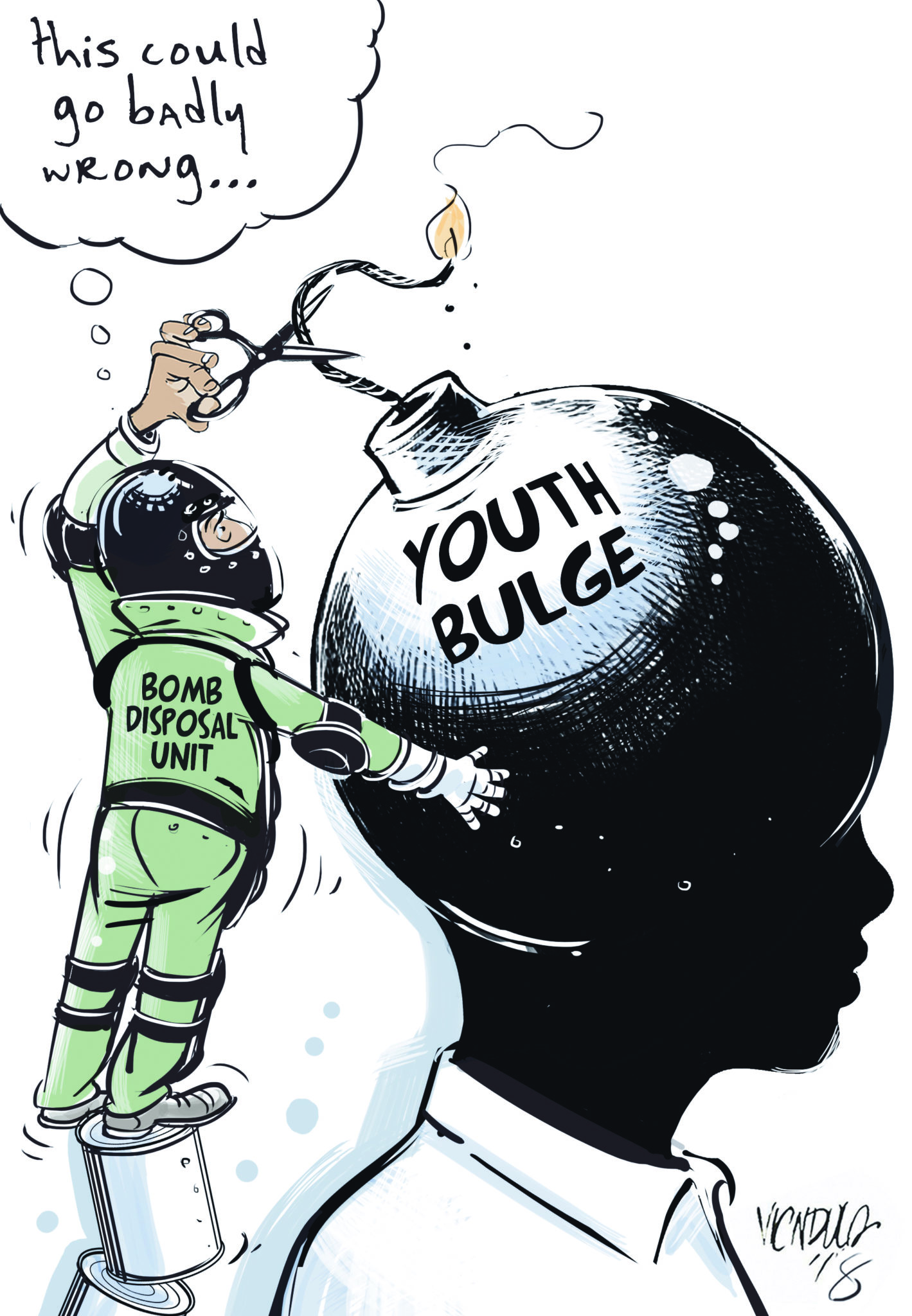

There are also concerns around the question of how to counter the potential challenges for social, economic, political and security policy from a large, restive youth population.

Firstly, it is important to note that the gap between modern economies and African markets is growing. Leaders talk about the challenges posed by the fact that some 60% of Africans are under 30 years old, but they seem unable or unwilling to recognise that this has real implications for their countries. This is despite the constant reminders from scenario planners, technology buffs and consultants. A new world is upon us – one in which traditional sectors and jobs are being disrupted by technology and replaced with artificial intelligence and robots.

This trend has been given a name – the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). The term was coined by the World Economic Forum to describe a digital age in which technology is disrupting existing business models and sectors and, importantly, jobs. Meanwhile, much of Africa is viewed as being stuck in the Second Industrial Revolution, with governments prioritising industrial programmes and skills that will be disrupted, and even marginalised, by current technology trends, which present both huge opportunities for tech-savvy young entrepreneurs but also major challenges for employment for millions of unskilled young Africans.

There are pockets of Africa – sectors rather than countries – that have leapfrogged into the Third Industrial Revolution, in which the technologies of ICT and electronics are the drivers of change. Africa’s underdevelopment has provided a clean slate for technological innovation that bypasses traditional models to address longstanding challenges.

Energy is an example. With millions of Africans still far from a power grid, renewable energy innovations are reaching across the continent. An initiative in Kenya, M-Kopa Solar, has in five years connected more than half a million homes to its pay-as-you-go solar solution for rural and low-income households. It is now rolling out in Tanzania, Uganda and Ghana. In another example, the mobile revolution has highlighted the enormous appetite for technology and entrepreneurship among Africans, particularly the youth. Africa has seen the highest mobile phone growth of any region over the past decade.

According to the Mobile Ecosystem Forum, the continent has a subscription penetration (percentage of the population) of 82%, which is expected to reach 100% by 2021. Much of this growth will come from the new generation. This is also increasingly being shown in the banking sector. According to the UN, 12% of adults in Africa have mobile bank accounts as compared with 2% of adults globally.

In Kenya it is as high as 58%. IBM CEO Ginni Rometty has coined the phrase “new-collar jobs” to describe work that doesn’t require a traditional degree but does require high skills levels in areas such as cyber security, data science, artificial intelligence and the cloud. This describes workers who sit somewhere between “blue collar” and “white collar” on the traditional work spectrum. She first raised it in 2016 in an open letter to then president elect Donald Trump, detailing ways she felt Americans could benefit from advances in technology.

The private sector, recognising the potential opportunity – and challenges – of Africa’s demographic, has stepped in, focusing efforts on these “new-collar” jobs. For example, IBM has, with the UN, launched a $70 million initiative to create jobs in Africa, focused on digital literacy. It aims to train 25 million youths over five years, kicking off in five countries – South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, Morocco and Egypt.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s Digital Jobs Africa initiative offers skills training and linked job opportunities for Africa’s young people. More than 150,000 youths have already been trained and 455,000 connected to jobs. There are many other international initiatives of this kind. But these efforts are not limited to international interventions.

Africans are also coming to the party. A leading player is Nigerian philanthropist and businessman Tony Elumelu, chairman of Heirs Holdings. His foundation is spending $100 million on entrepreneur training programmes in Africa. Africa’s youths are its future and their fate cannot be left to chance, he told Africa in Fact. “Africa’s development will have at its heart young African innovators and their transformative ideas. Only they will create the millions of jobs Africa needs.”

The African Development Bank Group (AfDB) has launched a “Jobs for Youths” strategy to create 25 million jobs over 10 years. African millionaire Ashish Thakkar, chairman of pan-African investment firm Mara Group, is a member of the AfDB’s Presidential Youth Advisory Group. He says it is vital that Africans acquire the right skills sets for the future.

“With artificial intelligence and everything else that is happening, the reality is that what we are training our youth for today may not be relevant in 10 years’ time,” he told Africa in Fact. “So it is important to see how we can create systems and thinking to get them to learn, unlearn, and relearn when necessary.” Similar initiatives are gaining traction. Technology hubs are driving innovation across the continent. According to the mobile operators’ association, GSMA, there were 314 technology hubs in 93 cities across 42 countries in 2017, and the number is growing.

Non-governmental organisations are playing a key role in delivering innovation to communities around Africa. But the initiatives currently in play are a drop in the ocean compared to the need. Meanwhile, the continent’s leaders, who might have been expected to take a lead in such an important matter, appear to be stuck in redundant ways of thinking that have not delivered development over the past few decades, let alone knowledge-based economies.

The continent’s developmental challenges are still enormous. Out of the 37 countries listed in the 2017 Low Human Development category of the UN Human Development Index, some 31 are African. This is what young people stand to inherit. The popular view that rising labour costs in China will lead to millions of low-skilled jobs relocating to Africa is optimistic, given the automation of work globally and the lack of skills and low productivity in Africa.

There is a concern that digital transformation could increase Africa’s income gap even further, given the challenges in education. The new skills and competencies required by 4IR are not being taught in schools in Africa, where thousands of children don’t have classrooms, let alone computers. Connectivity in Africa still trails behind at 21% as compared to the global average of over 40%, and more than 70% in the European Union, according to the International Telecommunications Union.

Rather than stimulating entrepreneurship, policymakers are regulating it. A general lack around the continent of enabling policy in this regard is acting as a handbrake on progress. Governments in Africa don’t understand the integral role that technology can play in an economy, according to Ghanaian Bright Simons, president of digital company mPedigree Network. They treat it as a marginal factor, and fail to see that it is a transformational sector that, properly stimulated, could increase economic inclusion and growth.

Africa is not short of young entrepreneurs with good ideas, ambition, energy and talent, which can be harnessed to drive more inclusive growth. Young people are also impatient for change. As their access to information increases, they will gain more power to hold their leaders accountable, and to push for a new political agenda that will allow them input into the processes and policies that shape their lives.

But digitally savvy young Africans across the continent are mostly being left to forge their own paths through a rapidly changing world. If Africa is to realise and build on the opportunities presented by 4IR, a radical mindset change at the policy level will be necessary. Policymakers should be seeking every opportunity to support, and not hinder, the modernisation of African economies. Young people are increasingly recognising that this is the only way to build a decent future for themselves, and one day, their children.