Good Governance Africa: Statement on COP27

21 November 2022

COP27, the 27th iteration of the UN climate change conference, has just concluded in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. It was a tense and sometimes deeply emotional conference. One participant at the conference described it as feeling like an “existential battle zone” between “climate, biodiversity, life and wellbeing on the one hand, and predatory fossil fuel, financial and exploitative power structures and interests on the other”.

Good Governance Africa observes with concern that a number of important issues regarding climate change were left unaddressed or subject to compromises that leave Africa, in particular, inequitably exposed to climate change.

A major achievement

It needs to be recognised that the major achievement of the conference was an agreement to establish a fund to help vulnerable developing countries. As Molwyn Joseph, Antigua and Barbuda Minister and chair of the AOSIS group of small island nations said, the agreement represented a “mission of 30 years in the making”. This achievement needs to be celebrated even if details of the fund were left to transitional negotiations leading up to COP28 in Dubai.

It remains to be seen how this new funding mechanism will work and whether developed nations will keep to their commitments. The adaptative and mitigation finance mechanisms to help developing countries better handle the brunt of climate impacts have been routinely ignored.

This achievement aside, the conference left key issues relating to climate change either unaddressed or subject to worrying compromise. Good Governance Africa is concerned that the Global North’s responsibility for climate change was not sufficiently recognised at COP27. It is also of concern that disunity, attempts to distract from our own responsibilities and a lack of urgency regarding the impact of climate change on local communities continue to detract from African efforts to deal with climate change effectively.

Climate activists demonstrate at the Sharm el-Sheikh International Convention Centre, in Egypt’s Red Sea resort city of the same name, during the COP27 climate conference, on November 16, 2022. (Photo by Fayez Nureldine / AFP)

The global north’s responsibility

One major concern was the failure of the conference to sufficiently acknowledge the Global North’s responsibility for the effects of climate change.

Africa is impacted disproportionally by climate change – yet the continent’s total emissions only constitute around 4% of global emissions. The WMO’s State of Climate in Africa report (2020) indicated that by 2030, nearly 120 million people living in extreme poverty (i.e. living on less than US$2 a day) will experience longer warmer seasons, shorter colder seasons, increased heat waves, and exposure to water stress and hazards like withering droughts and devastating floods. This has a direct impact on economic, ecological and social systems that threaten to disrupt all aspects of human security, from land and food to infrastructure and access to water.

Attempts to address climate-vulnerable countries were first made at COP15, where a commitment to mobilising $100 billion in finance for climate adaptation was agreed upon. Formalised at COP16, and reiterated at COP21, by 2019, developed countries had yet to meet their pledge and only managed to deliver $80 billion. The UN Trade and Development office has estimated that for vulnerable countries to adapt successfully by 2030, approximately $300 billion will be needed. Thus, the pledge to double adaptation finance still falls short.

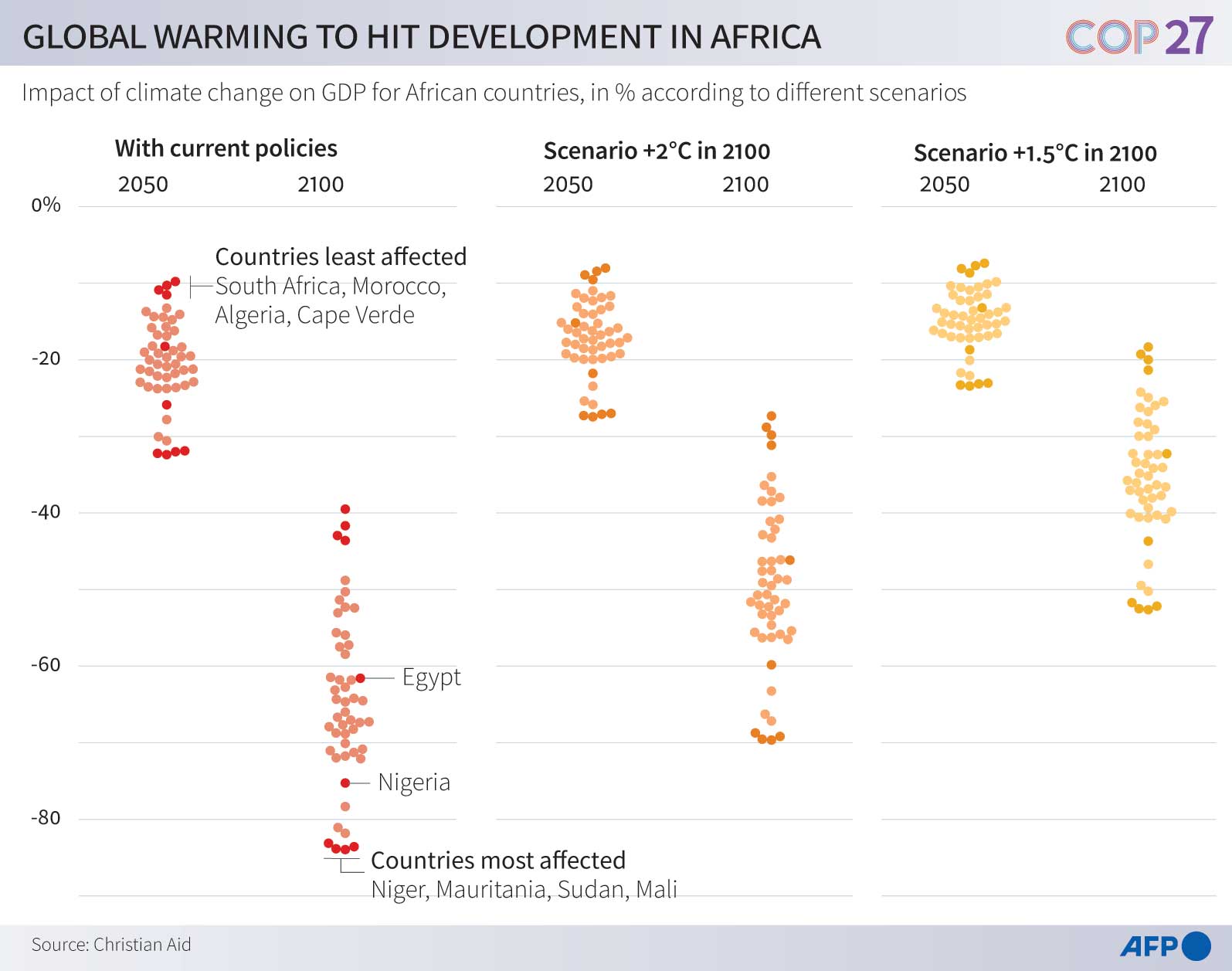

The need for funding to help nations adapt to the impacts of climate change, and mitigation funding to help nations lower their carbon footprint, has been agreed in principle. However, developing nations called for the establishment of a loss and damage fund to compensate them for losses they have already incurred or will incur in the future through efforts to keep global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The world’s 20 most climate-vulnerable economies, for example, have lost approximately $525 billion over the past two decades as a result of climate change. African countries have experienced losses ranging from -15 to -10% of their GDP per capita growth.

To date, loss and damage funding has remained a contentious issue. Developed nations are concerned that committing to a loss and damage fund will expose them to legal liability and future litigation. Some developed nations are concerned that paying for such a fund may be interpreted as admitting culpability, which may result in future legal battles. The US and the EU continue to sidestep the loss and damage issue while simultaneously investing in and benefiting from African fossil fuel projects.

African disunity

African countries’ commitment to a unified front as regards climate change is also questionable. In the run-up to COP27, the African Union and the African Group of Climate Negotiators (AGN) could not agree on the role of gas in a just and equitable energy transition. In August, the AU proposed that the continent “continue to deploy all forms of its abundant energy resources, including renewable and non-renewable energy, to address energy demand”. The AGN rejected this. At least 10 African nations support gas as a “transition fuel” and the Egyptian government has been seeking oil and gas deals.

At CO27 this signalled opportunities for outside actors to use these divisions to their advantage, while it also detracted from the conference’s focus on other important issues of climate change, such as loss and damage funding, adaptation finance, and the like. Egypt, which hosted the conference, sided with the US, the EU, China, Gulf countries, Japan, and others to block a clear agreement on a just and equitable phasing out of all fossil fuels.

It is true that African countries spend an estimated 2-9% of GDP – between $56.6 billion and $232.2 billion annually – on tackling climate change. Yet the annual costs of building resilience could range from $140 billion to $300 billion by 2030. On the administrative level, senior continental officials say that governments’ capacities at institutional and human levels to meet international standards and funding eligibility requirements are inadequate. The continent needs more area experts with international climate change negotiation skills and the knowledge to navigate complex issues such as carbon trade deals. Activists say that funding provided by institutions such as the African Development Bank is being diverted for political purposes.

There is a lack of political will to implement climate change measures. African countries have yet to commit to a pan-African, binding strategy to make key sectors such as agriculture, water resources, and infrastructure more climate resilient. This could be done using the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to implement and manage, for example. The AU’s climate strategy is currently non-binding. Commitment to cross-continental measurable goals is needed, as well as knowledge sharing, institutional coordination, regional and trans-continental policies and frameworks, and improved regional coordination. The AU, in particular, needs to support African countries’ efforts to serve a long-term vision, rather than looking on while national elites seek short-term quick wins that benefit a few.

African distractions

African distractions

African leaders should not use the backsliding of major economies as an excuse to distract from the poor governance and mismanagement of resources in improving energy security and meeting their socio-economic developmental goals. For instance, Nigeria and Angola remain energy poor despite being oil-wealthy countries. This is due to several driving factors, including corruption and maladministration. Both countries have failed to translate their oil wealth into inclusive and sustainable development. Developing countries have reasonable concerns over being locked into the expensive arrangements entailed in renewable energy projects. However, innovative arrangements can be developed that are less costly in the long run than being locked into dirty alternatives that are typically subject to cost overruns and unproductive rent-seeking. Divestment from fossil fuels can actually provide opportunities to reverse the negative historical relationship between environmental degradation and income per capita.

More than 600 million people in Africa still lack access to electricity and this challenge must be prioritised and addressed by African governments. African countries have vast quantities of minerals and metals that are required for the global shift to low-carbon economies and technologies. Our focus should be on exploiting these resources in ways that develop the continent’s capabilities to optimally tap into global value chains associated with new products such as solar panels, electric vehicles, batteries and wind turbines.

With adequate time and finance, Africa is primed to transition to renewable sources and support a green energy transition in the global economy. Ultimately, there can be no climate justice without energy justice and climate compensation. Africa must be allowed to prioritise industrialisation independently to achieve its development goals, at its own pace and within sustainable, achievable frameworks.

Local government impacts

Good Governance Africa is particularly concerned that the inability to find consensus in dealing with the climate crisis at the global, regional and national levels should not distract from paying attention to the critical role local governance structures have in preparing for ongoing disruptions. It is commonly acknowledged that some of the most potent consequences of natural disasters, inadequate infrastructure and environmental degradation fall on local communities. This combination of weak governance and the greater frequency of natural disasters impedes democratic accountability, minimises economic development and aggravates instability at the local level.

In 2022 alone, a series of events, including flooding in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa; several tropical storms in Madagascar, Malawi and Mozambique; and drought in West Africa have caused substantial loss of life and livelihoods at the local level. In each case, the lack of urgency felt by local officials in these areas exacerbated current crises while reducing the capacity to deal with future crises. These failures included the lack of clear municipal disaster management plans and systems; poor road maintenance; and the inability to protect communities located close to rivers and steep slopes.

To meet the moment, local government structures must focus on adapting their planning systems to deal with the ever-rising risk of natural disasters, invest and maintain environmentally sustainable infrastructure and supply chain networks, and support the most vulnerable in their communities. Local officials in places like Accra, Ghana and Nairobi, Kenya have led the way through initiatives which use energy-efficient building materials, and rehabilitating water harvesting and storage systems, while also protecting residents in informal settlements. It is imperative that local government structures across Africa pursue similar initiatives, particularly given the absence of regional and national leadership on these issues.

Conclusion

The fund to help vulnerable developing countries agreed upon at COP27 was a major step forward. Yet, as we have noted, there are still major reasons for concern regarding global progress on climate change.

In our view, the threat to the planet represents a “super-wicked” problem that involves an extreme pressure of time, the involvement of the very people who caused the problem in solving it, and the strong temptation for leaders to discount the future and opt for short-term gains, often for themselves. This is in addition to the governance and technical challenges we all face.

It is no surprise that many from developing nations, and Africa in particular, are dismayed at the recent European “dash for gas” in consequence of the Ukraine war, with investors and bankers pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into gas production in Africa just when this form of energy is supposed to be de-emphasised as part of a “just energy” transition. In effect, and again, this is an example of the global north seeking to ensure its own development at the cost of the planet while drawing resources from the developing world.

Dealing with the threat to the planet will require measure and maturity. In that light, African countries also have responsibilities to live up to. We owe it to younger generations to eschew expedience in favour of innovative responses that override the free-rider problem currently riddling the global collective action we so urgently require.