An Australian phosphate mine in Togo. Image Wikimedia Commons

The big players in Australia’s mining sector have grown wary of Africa’s regulatory requirements, but smaller miners still take chances on the continent

Seen from an investment perspective, the pattern of engagement between Australia and sub-Saharan Africa has largely been dictated by the mining and mining services sectors, and, more specifically, the commodity cycle. This should come as little surprise given the Australian economy’s historic and current heavy reliance on the extractives industry and the sheer magnitude of sub-Saharan Africa’s untapped mineral wealth, estimated to account for 30% of the world’s mineral reserves.

Because mining is so heavily dictated by the commodity supercycle though, the pattern of Australia’s engagement with Africa has, inevitably, resembled a rollercoaster. The steady upward trajectory of investment and development aid from Australia into sub-Saharan Africa between 2005 and 2013 was followed by a drastic and near-continuous plunge in line after the commodity price bubble burst at the end of 2012.

At the start of the new millennium Australia’s engagement with the continent was at the bare minimum: trade and investment relations were negligible, and only two percent of the country’s entire official development aid budget was directed to sub-Saharan Africa. But in the early 2000s two factors combined to transform Australia’s attitude to financial participation in the continent.

The first of these was the mining boom, the like of which had not been experienced since the late 19th century. It began in around 2003, when prices for metals and minerals, which had been depressed for more than a decade, began to rise substantially on the back of an almost insatiable demand for raw commodities from industrially ambitious Asian countries. The phenomenal increase in commodity prices inevitably led to a surge in exploration activity and mining production across the globe, with juniors and majors alike hoping to cash in on increased output and new discoveries.

Australia was already well explored and much of its mining industry was in a mature stage of development. Australian miners and investors believed that the only way to take full advantage of the commodity upswing would be to pursue exploration and development projects overseas. Africa was, and remains, the most under-explored mineral jurisdiction in the world, and gung-ho Australian companies joined their Canadian, British, Chinese and South African junior counterparts in the new “Scramble for Africa”.

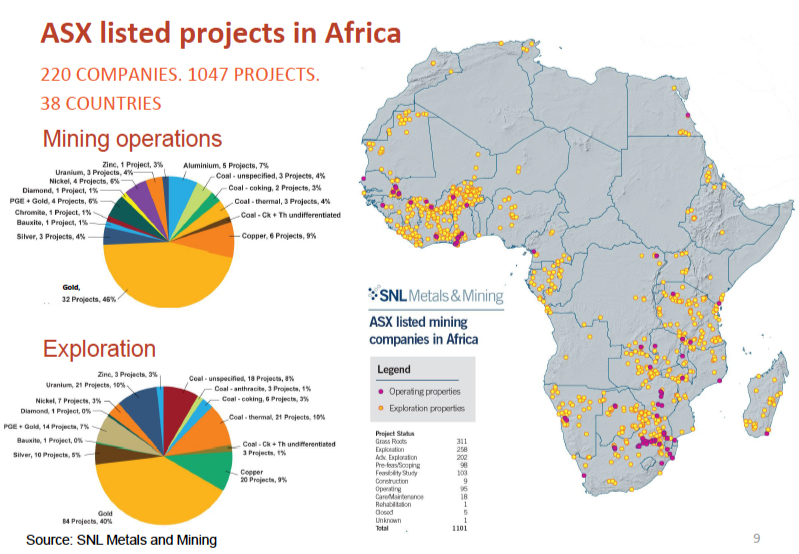

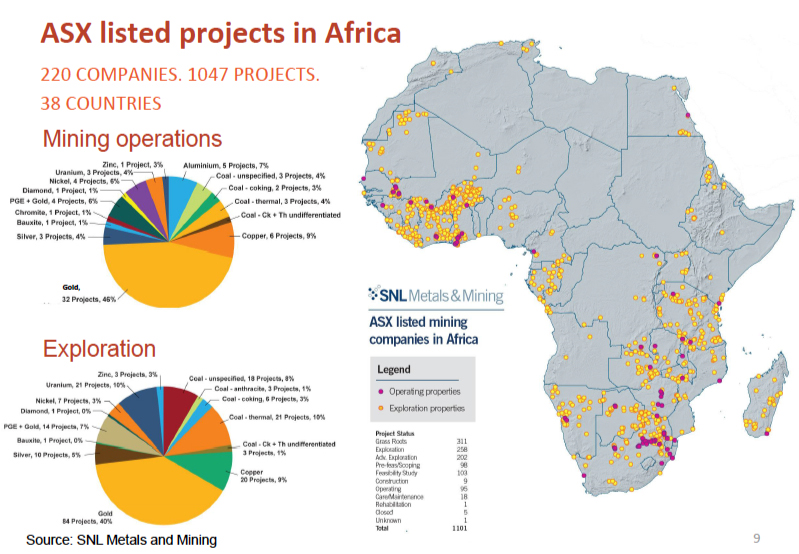

Since then Australia’s investment in sub-Saharan Africa’s mining sector grew significantly – until the peak of the commodity boom at the end of 2012. While only 80 companies had interests, either as explorers or producers, in southern Africa in 2006, by the end of the decade 230 companies were pursuing 650 projects across 42 African countries. By the beginning of 2013 the number of projects had mushroomed to over 1,100 at a value of more than $50 billion. It was a significant investment into sub-Saharan Africa: the region accounted for more than a third of Australia’s entire offshore mining investment of

$143 billion for that year.

During this period Australian Securities Exchange (ASX)-listed companies contributed substantially to the growth of Africa’s mining sector. The in-ground value of the discoveries made by ASX-listed companies between 2008 and 2013 – the period with the highest Australian-driven prospecting activity – amounted to $687 billion, according to research undertaken by SNL Financial in 2014. The high rate of Australian-financed exploration across the continent resulted in the commissioning of some 60 mining operations, including 15 in the coal sector, 11 in platinum group metals, nine in gold, six in diamonds, and five in uranium.

ASX-listed mining companies operating in Africa

© International Mining for Development Centre

The growth in investment and the cementing of Australian capital into Africa’s mineral-rich rock was mirrored by a substantial increase in development aid funding to the continent over the same period. Australia spent only $82,5 million on development aid in Africa between 2005 and 2006, but by the end of the decade that figure had more than doubled to $200,9 million. By 2013/14 the aid budget to Africa increased to more than $350 million.

At the peak of that budget expenditure, a statement from Australia’s International Development Assistance Programme said it was in the country’s interests to help to ensure good governance and peace and stability on the continent, as well as facilitate better infrastructure and skills through development aid funding. “Australia has significant political and economic interests in the stability, security and prosperity of Africa. Australia’s trade has grown steadily over recent years and is served by greater peace and stability in the region. High rates of economic growth in Africa are creating opportunities for Australian businesses, especially in the mining sector.”

However, mining is cyclical and the commodity boom could not continue indefinitely. The bubble burst at the end of 2012 following a marked decline in the demand for minerals and metals from a highly saturated Asian market. Demand for commodities has remained relatively depressed over the past four years, with a consequent drastic slump in market prices to almost pre-mining boom levels.

The sustained slump in commodity prices has resulted in a substantial decline in Australian investment and interests on the continent. In fact, according to Nicki Ivory, Western Australian mining leader for Deloitte, the number of Australian projects almost halved from the 2013 peak to just 590 in 2016, with the most drastic cut experienced in the field of greenfield exploration. This has resulted in huge write-offs and a fall in total foreign direct investment into sub-Saharan Africa from over $50 billion to just $30 billion last year.

At the same time Australia cut its official development aid to Africa by more than 70%, with the 2016/17 budget earmarking just $89,5 million to the continent. Andrew Dinning, board member on the Australia-Africa Minerals and Energy Group, insists that the increase in aid up until 2013 had little to do with the country’s economic interests but was undertaken in the hope that Australia would secure a seat on the United Nations (UN) Security Council. (By increasing aid, it was believed that Australia could “buy” the votes of key African nations in the UN election.) The decline also coincided with a change in the Australian government in 2013, with the new administration becoming increasingly insular in its policies.

While the debilitating decline in commodity prices and investors’ subsequent waning interest in funding mining projects has been the principal factor in the decrease in Australian investment on the continent, it is certainly not the only one.

Australian mining companies were rather gung-ho in their approach to African exploration and project development in the boom period, but they have become considerably more risk-averse in recent years.

The major mining houses have adopted a particularly risk-averse sentiment, with some opting to divest from their African interests over the past few years, says Ivory. The juniors still have some appetite for risk, because their activities are largely dictated by the sentiments of increasingly savvy investors, but they have become more discerning regarding the commodities and individual African jurisdictions in which they invest.

That growing caution over political and economic risk has been compounded by increased legislative uncertainty in many of the major mining jurisdictions across the continent. The lack of solid legislative frameworks, ever-changing mining codes and unfavourable tax regimes have made doing business in certain countries difficult for mining companies and frustrated investors who have little tolerance for uncertainty.

This is most evident in South Africa, where ASX-listed companies are involved in more than 130 projects. The country’s regulatory administration has been mired in uncertainty for well over two years with continuous stalling of the promulgation of a governing minerals act. According to Dinning these challenges have been compounded, across the continent, by ubiquitous bureaucratic red tape, corruption, and ever-moving goal posts.

Latin America is becoming an increasingly attractive investment destination for explorers and producers, says Ivory. The continent has a well-established mining sector, which presents opportunities for the Australian mining equipment, technology and services sector. It also has an appealing untapped resource base. These factors make it ideal for the risk-taking Australian juniors.

While the improvement in commodity prices over recent months tentatively points to a recovery of the African mining sector, Ivory believes that Australian investment and participation on the continent will never return to the 2013 level. “However, I think the commitment is there because of the massive resource prospectivity of the continent, which combines well with the entrepreneurial and risk-taking nature of many Australian miners and the equity investors who fund them,” says Ivory.

Australian Securities Exchange-listed firms still dominate foreign direct investment into the African mining space and will continue to do so over the short- to medium-term.

In the future, gold, which already accounts for some 40% of project activity on the continent, will continue to dominate the attention of Australian explorers and producers alike. Sub-Saharan Africa is well endowed with the precious metal, while small operations can be relatively cheap – between $150 and $200 million – to establish. In addition the product is far easier to move than bulk materials, which require substantial infrastructure.

The sentiment towards gold as a safe haven commodity in an uncertain world remains strong. Other favourable prospects in Africa include metals – particularly graphite, used in batteries – for which there has been a surge in demand and consequent increased investor appetite.