In weakly institutionalised contexts, natural resource wealth tends to be a curse instead of a blessing. Where citizens are relatively powerless to hold ruling elites to account, resource wealth undermines development prospects. To the contrary, where citizens are able to exert constraints on the use of executive power, resource wealth can generate development outcomes that benefit ordinary citizens.

The term ‘resource curse’ was originally coined by development scholar Richard Auty in 1993, and the first econometric work on the subject was published in 1995 by economists Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner. Manifestations range from deepening authoritarian rule to widespread corruption and even civil war.

Where citizens are relatively powerless to hold ruling elites to account, resource wealth undermines development prospects.

It is a wicked problem. In other words, its causes are typically multi-faceted and the interconnected nature of variables at play make causal feedback inconsistent and unreliable. Linear, single entry-point interventions don’t work in these cases. Rather, there has to be a simultaneity of responses that is most appropriate to treat the particular anatomy of the problem in its own specific context. Oil, for instance, seems to produce its own peculiar set of problems and largely correlates with autocratic regime entrenchment.

The Oil Curse

Sub-Saharan Africa’s two largest oil producers respectively, Nigeria and Angola, clearly exhibit an apparently oil-related set of problems.

In 2018, Angola’s fuel exports constituted 92.4% of the country’s total exports. Oil rents – the difference between the price of oil and the average cost of producing – accounted for 25.6% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Yet, the country ranked 148th in terms of human development in 2019.

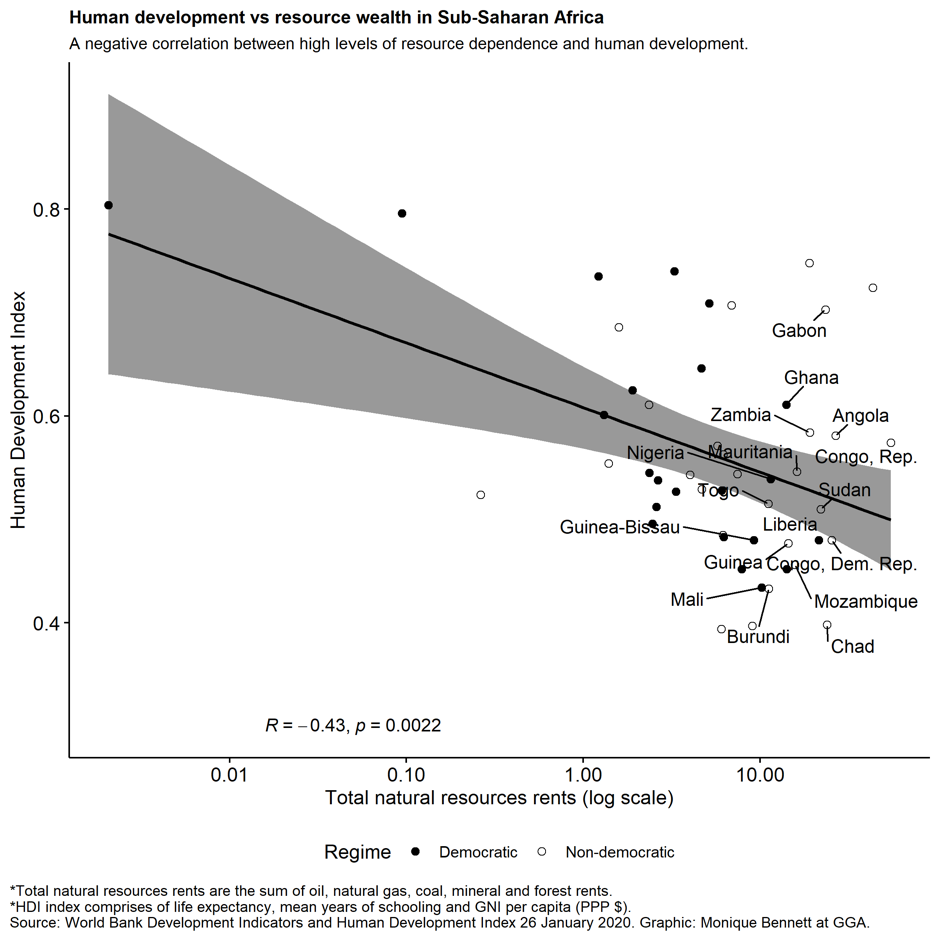

Nigeria’s fuel exports in 2018 were 94.1% of total exports, oil rents amounted to 9% of GDP and it ranked 161 in terms of human development in 2019. As is clear from the graph below, sub-Saharan Africa’s major oil producers are clustered around the lower end of the human development spectrum and are mostly autocratic. The latest Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index records that there are now 57 “authoritarian regimes” as opposed to only 23 “full democracies” of 167 countries evaluated. The vast majority of authoritarian regimes are in Africa; most are resource-wealthy. Democracy is not in rude health at all.

As is clear from the graph below, sub-Saharan Africa’s major oil producers are clustered around the lower end of the human development spectrum and are mostly autocratic.

Both Nigeria and Angola were characterised by autocratic rule of one form or another for most of their post-independence histories. Autocracy invariably undermines a country’s development prospects. This forms part of a deeper puzzle of interest to political scientists: why some dictators last only a few months in office while others last decades. In Angola, José Eduardo dos Santos ruled for 38 years. In Nigeria, no aspirant autocrat lasted in office for more than 10 years. These divergent institutional and development outcomes require explanation.

While the resource curse literature has done an adequate job of describing the general nature of the relationship between resource dependence and underdevelopment, it needs to now focus on understanding specific manifestations. In my latest book, I detail the anatomy of how the oil curse has played out in Angola and Nigeria respectively.

Why do some autocrats last for decades and others for only months?

I selected an off-the-shelf game theory model developed by Milan Svolik, to explain why dos Santos was able to secure power for 38 years while Nigeria was racked by multiple successful coups. The model is simple: At any moment in time, the aspirant autocrat can choose to acquire more personal power at the expense of his ruling coalition or maintain the status quo – a power-sharing equilibrium. In response to either move, the remaining members of the coalition can accept the status quo or launch a coup (normally in response to a power-grabbing move). Autocrats are rarely removed by external intervention, so Svolik rightly discounts external factors such as the role of opposition parties.

In Angola, which achieved independence from Portuguese rule in 1975, Augustinho Neto came to power for the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA). He died on a Moscow operating theatre in 1979. The country was already at war with itself, with União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA) leader Jonas Savimbi leading the charge within a year of independence. A disastrous 1977 coup attempt by disgruntled MPLA members in Luanda resulted in a retaliation massacre of which still relatively little is known. Dos Santos then came to power when Neto died in 1979. Within six years of his rule, he had ousted any potential viziers and consolidated an iron grip on power. The remaining members of the ruling coalition, in response to each power-grabbing move, were never able to credibly launch a coup. Dos Santos used the extensive oil rents at his disposal – and the cover of civil war – to consolidate wealth and power, neutralising the opposition and allowing his generals to amass wealth through various schemes. That he was eventually upended by members of his own ruling coalition (in 2017) is unusual, but likely explained by having placed family beneficiaries in plum positions ahead of loyalists.

In Nigeria, the balance of power at independence in 1960 was just as precarious as Angola’s but for different reasons. The North was like a different country to the South. The differences remain stark to this day. By contrast, however, the country had experienced two military coups in short succession within 1966. In 1967, it plunged into a tragic three-year civil war. But neither the coups nor the civil war were driven by oil. Oil wealth only became a major factor in Nigeria’s political economy in the early 1970s and exacerbated the pre-existing fragility. Punctuated by brief civilian rule spells, military rule continued until 1999. Contrary to the Angolan situation, however, coups remained prevalent right up to 1993. The 1993 coup brought the ruthless Sani Abacha to power, who stole vast oil wealth but died in 1998 of unknown causes. His successor, against all expectations, returned the country to civilian rule in 1999. Deep fragility remains, but the post-Abacha era has seen a more open and competitive political settlement emerge.

Where to from here?

The book reveals that the resource curse manifests differently in different contexts even where the same resource is present. If governance interventions are to be useful, they must seriously understand the context first so as to gain traction. Linear, single-entry interventions are unlikely to produce lasting fruit.

At Good Governance Africa, we have launched a campaign to draw attention to this very issue. And as democracy all over the world battles backsliding (despite Biden’s historic US victory), the call to strengthen institutions that check elite power could not be more urgent.

As outlined above, the resource curse is a wicked problem with no silver bullet in sight. Rather, addressing it requires the hard work of collective action, the engagement of all affected stakeholders, and governance interventions that speak to the realities of the problems as they play out in specific contexts.