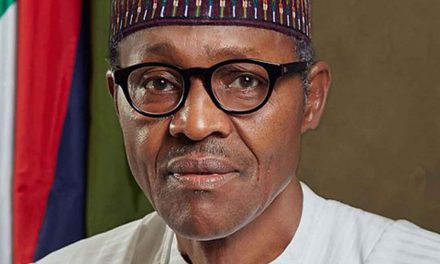

Kekes on Siaka Sgevens Street, Freetown. Image: Ernest Henry

Informal transport operators in the Sierra Leone capital face levies, bans, fines and government disregard

Ibrahim Shaw has driven a taxi in Freetown for 16 years. The constant sound of his horn as he weaves in and out of traffic in Sierra Leone’s capital city announces his impending arrival to potential customers waiting by the

roadside.

Shared taxis – a system where a seat is bought for part or all of the driver’s intended route – are one of the most convenient, affordable and popular ways of navigating the city. A one-way journey costs Le1,500 ($0.20), while two people can pay Le2,500 ($0.33) – a 50% increase on 2015 fares, driven by the government’s decision to remove fuel subsides in 2016.

But taxi drivers do not have a monopoly over the city’s transport. Okadas (motorbikes) are omnipresent outside the city centre, since the government banned them from the central business district in 2016. They provide a quicker – though often more dangerous and expensive – option for navigating Freetown’s gridlocked streets.

A new transport option, the keke, a three-wheeled motorised tricycle, has also become more prevalent and popular across the city since the imposition of restrictions on okadas. All are integral to the functioning of the city and its economy. Not only in the number of informal jobs they provide for young men – few women work in the sector

– but also their services allow those with jobs, in both formal and informal sectors, to commute on a daily basis. Public transport in Freetown, aside from a couple of Chinese-funded government buses, is non-existent.

The majority of informal transport operators in the city rent their vehicles for around Le50,000 ($6.50) a day; a fee they are expected to pay regardless of the sums they recoup. On top of this, they have to account for fuel costs and factor in less-frequent outlays for vehicle maintenance and encounters with the police. “You can work all day and still lose money,” Ali Bangura, an okada rider in Freetown told Africa in Fact, “but on a good day I can make 50,000 Leones.”

This unpredictability and insecurity is lamented by taxi driver Shaw: “You can work for 20 years and yet you still don’t have land or a house. This is a big problem. When you are old you are going to be a beggar on the street.”

Interaction between transport operators and the state comes mainly through the police. Roadblocks exist at key junctions across the city: Congo Cross, Lumley, St John and Aberdeen Road to name a few. Here bribes, ranging from between Le30,000 ($3.96) and Le60,000 ($7.92), are extracted, often for minor offences such as stopping illegally, faulty break lights or driving without a licence.

These are not insignificant sums for people operating on the margins but the payments are “part and parcel of operating in this sector,” says Shaw.

An Afrobarometer study of attitudes towards police corruption in 2015 found that 69% of Sierra Leoneans thought “all or most” of the police were corrupt. The country also scored the joint highest on the continent (36%) of people who had paid a bribe to police in the last year.

Ali Bangura, an okada rider. Image: Ernest Henry

Bangura carries two helmets, one for himself and one for his passenger, and holds a valid licence, which he bought for Le700,000 (about $93) to comply with regulation, but he still faces police harassment. Increasingly, drivers are not renewing or obtaining licences because it makes no difference to the way the police treat them.

This points to a lack of connection between city-level efforts to regulate informal transport and the ways those measures are enforced in practice. The lack of a proper channel to dispute police decisions is a constant source of frustration. Refusing to submit to police requests can lead to vehicles being confiscated, with the costs involved in reclaiming them through the justice system running to over $100. Many choose to pay the bribe, if they can.

In theory, taxi and okada operators have mechanisms through which they can air grievances. Union membership costs Le1,000 ($0.13). These associations, which usually centre on the riders’ areas of operation, aim to provide drivers with legal advice and support when they encounter trouble with law enforcement officials. But Shaw’s own experiences have left him sceptical about their ability to deliver on promises of legal support and to negotiate effectively with the police.

Unions struggle to get the voice of transport operators heard in interactions with the government. Joseph Lamboi, chairman of the okada riders’ association for Western Area Rural, acknowledges that opportunities to speak with the interior ministry and police do exist, but admits they rarely find a receptive audience. The enforced ban on okadas in the central business district is just one example of them “not listening”.

Under the stewardship of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Paolo Conteh, the 2016 ban has proved more durable than previous efforts. The rationale for its introduction was an attempt to alleviate traffic congestion in the city centre and to improve road safety for both users and pedestrians.

However, the government’s failure to come up with alternatives for okada riders leaves them struggling for income and their passengers in need of new forms of transport.

Yet the situation has also given rise to creative solutions. The number of kekes, which are not affected by the ban, has grown dramatically in the past year, to fill the gap left by the banned okadas. The operators are former okada riders who have switched modes of transport in an effort to find an income.

But although the vehicles they now use are different, the environment in which Freetown’s transport providers work has, in many ways, remained the same, and issues of congestion and road safety remain unresolved.

Ibrahim Shaw, a Freetown taxi driver. Image: Ernest Henry

The government’s approach to the issue of city transport continues to be driven by short-term thinking aimed at quick wins. With elections scheduled for March 2018 – and informal transport workers regarded as an important tool for campaigning as well as a voting bloc – it is likely that both parties will make promises aimed at informal transport operators. But the likelihood of real action on these promises is slim.

Despite overtures towards okada riders during his 2012 election campaign, President Ernest Bai subsequently banned them from operating in the city centre, less than a year after his re- election.

“Visions of modern Freetown are rarely accompanied by alternative solutions for dealing with the traffic, transport needs and youth unemployment,” says Luisa Enria, a lecturer at the University of Bath who works on youth and identity issues in Sierra Leone. “Bikes are discussed as a nuisance, as lawless and as a problem, often without any recognition that without these forms of transport the city would come to a standstill.”

The economic impact of the current ban, squeezing the margins for youth riding okadas in Freetown, has been significant. More importantly, the ban delegitimises this type of work, impacting on the riders’ social standing. Bangura describes it as forcing him to ride in “the village part of the city” – highlighting both the economic and social impact of the government’s whim.

Lasting solutions to Freetown’s urban transport challenges will require a more collaborative approach to replace the current adversarial one. A good starting point would be for the government to recognise that without shared taxis, okadas or kekes, Freetown would grind to a halt.

“Even though the government may consider them as inappropriate actors, informal transport operators still have a right to the city,” argues Joseph Macarthy, co-director of the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre. He argues that their activities need to be regulated and absorbed into the daily operations of the city. “No matter what you think of these people, they are essential to its functioning,” he concludes.