Kenya President Uhuru Kenyatta. Image: Government of Kenya

The scion of the post-colonial Kenyatta political dynasty, Kenya’s president Jomo Kenyatta continues to enjoy popular support for his promotion of development

In public, Kenya’s third president comes across as someone who is warm and caring, and who has the interests of the country at heart. If you don’t love him for his warm personality, you’ll be drawn in by his youthfulness, his energy or his ability to communicate his government’s development agenda. If these qualities don’t impress you, then you might find his willingness to take on powerful foreign powers courageous and a national inspiration.

You would certainly notice his ability to silence his critics at home and abroad. The Kenya president’s frequent acts of kindness have earned him admiration at home and helped to shape his image as one of the continent’s most charitable and accessible presidents.

He made headlines in 2014 when he gifted a new house to a six-year-old girl who was living in squalid conditions with her struggling single mum in Gachororo slum, 20 minutes from Nairobi, Kenya’s capital. The little girl, Emily Wanjiru, became a national sensation after reciting a moving poem to the head of state at a public function. Kenyatta intervened through his agents when it emerged thatshe was living in abject poverty.

The girl’s case is not unique. President Kenyatta also adopted a secondary school student who had him in stitches with a humorous story at a State House function after winning the Schools National Drama festival. Kenyatta has put the lad, Daniel Owira, through high school and college after it emerged that he had been kicked out of school for failing to pay school fees.

When Kenyatta stops to buy groundnuts from a hawker or uses public transport or hosts schoolchildren at his official residence at State House, a camera operator is always on standby to capture the moment. The picture or video clip will be immediately circulated to his millions of followers on social media globally.

To keep this public image neat, the president has an army of bloggers on a payroll, who retweet and “like” his posts. His digital team employs social media influencers to endorse his messages. It is not a surprise that he ranked as the most popular leader in sub-Saharan Africa on Facebook, according to a 2016 study by Burson-Marsteller. The study was based on data collected in January 2016.

Kenyatta also ranks among the top presidents on other platforms, including Instagram. At home, every opinion poll conducted in the past year has shown him a clear favourite for the presidency in the August general election. As a president, Kenyatta, who grew up in the State House, when his father was the country’s first president, seems to have led a charmed life.

His privileged upbringing included attending prestigious schools in Kenya and abroad, among them Amherst College in the US. Yet Kenyatta mingles easily with the “man on the street”. This perhaps is another attribute that endears him across all classes in the country.

A recent poll by IPSOS Synovate said that most Kenyans who support his Jubilee Party do so because of its promotion of development. About 55% of respondents believed that the president’s party was pro-development, while only 22% thought the same of the opposition.

So, for example, the first phase of the $3.8 billion Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), running between Mombasa and Nairobi, is ready in time for the election. Meanwhile, more than two million new customers have been connected to the national electricity grid. Kenyatta has also made significant strides in the health sector, having delivered with free maternity cover.

However, none of these projects has been without controversy. The government has been accused of inflating the costs of the railway. The ministry of health has been dogged by a scandal, which culminated in Maythis year, with the suspension of $21 million in funding from the USgovernment.

In 2015, the National Youth Service (NYS) was hit by a scandal when it emerged that more than $7.8 million had been stolen from its account. A project aiming to deliver a laptop for every pupil in class has been delayed after the contracts were cancelled following allegations of fraud. The government has also been unable to explain which projects were funded from $3.8 billion borrowed from the Eurobond.

These failures have tainted Kenyatta’s record, and observers are critical of rampant corruption, tribalism and poor implementation of his legacy projects. Meanwhile, Kenyatta has begun campaigning to convince voters to continue supporting him. Early this year, he launched an online portal, months prior to the upcoming general election. It paints a rosy picture of his achievements, despite the fact that some of the successes he is claiming were inherited from the previous government.

Most independent analysts agree that his performance has been disappointing, as measured against his party’s manifesto. His failures, they say, have handed the opposition considerable ammunition, to the extent that he might end up becoming Kenya’s first one-term president.

Robert Shaw, a policy and economic analyst based in Nairobi, gives Kenyatta’s administration a low score on its handling of policy matters and management of the economy. “Overall, I would say the government’s economic record falls between mediocre to reasonable. I would give it a six out of ten. Governance and corruption are the weakest links. They have also been poor at implementation,” he told Africa in Fact.

Herman Manyora, a political analyst and a lecturer at the University of Nairobi says Kenyatta has not impressed as a president who seemed determined to “shake things up and make a difference”. Kenyatta’s big projects have looked good on paper but suffered from corruption during their implementation, he says. He blames middlemen and brokers, but also the president himself.

“I do not understand why a man like him, who comes from a wealthy family, would allow wheeler-dealers to tarnish his legacy projects through corruption. There is almost no big project started by his administration that has been free from allegations of corruption,” Manyora said in a telephone interview.

Kenyatta had done a “good job” with regard to security and the government’s efforts to contain terrorist organisation, al-Shabaab – which is based in neighbouring Somalia but makes incursions into Kenya – he added. For example, Kenyatta has made major changes in the top military and police organs to deal with terror at home.

He recently appointed a former army general, Joseph Nkaissery, to head internal security ministry. He also replaced the police boss and military boss, and the replacements say they are fixing systemic problems, such as previous failures to share and act on intelligence, which had made it easier for terrorists to carry out attacks in Kenya.

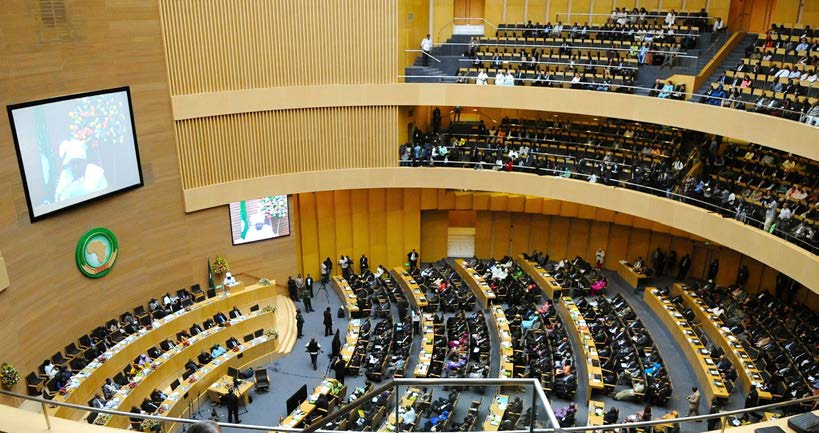

The International Conference Centre in Nairobi. © Daryona, Wikimedia

Kenyatta’s government is also spending billions of shillings on a military modernisation programme. Military expenditure is now one of the top three priorities of his government besides education and infrastructure. Last year, Kenya spent nearly $1 billion on its military capacity.

Nevertheless, Monyora, for one, remains critical of the president’s tenure in power so far. “Overall, though, he barely gets a pass mark. I leave it to Kenyans to decide whether he deserves a second term,” he commented.

Kenyatta’s main failure stemmed from his failure to appoint an inclusive government, Manyora said. Many senior state employees are either from his tribe, Kikuyu, or that of his deputy, Kalenjin. The lack of inclusivity in Kenyatta’s government is likely to be a major campaign issue for the opposition in the run-up to the general election, and could further reignite tribal tensions. During the 2008 election, more than 1,300 people were killed and over 600,000 others displaced as a result of ethnic violence.

According to a poll by Infotrack Research and Consulting in December 2016, some 60.6% of Kenyans were concerned that election-related violence would rear its head again. “If [Kenyatta] had created that feeling of inclusivity, he wouldn’t be facing the current threat of being a one-term president. The opposition wouldn’t have a chance,” Manyora said.

His views are partly shared by several other political analysts in the country. Patrick Lumumba, a former chairman of the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission, told a local television station last week that Kenyatta’s administration had performed “below average”.

“The current administration was elected on the basis that they would create jobs. But we are losing jobs on a daily basis. It was elected on the promise that the price of food would go down. [Prices] have gone up. On the promise that doctors would be paid. They have not been paid. On the promise that there would be inclusivity. That has not happened. Or the promise that corruption would be fought. If one were to be objective, this is a government that should be very worried,” Lumumba said.

He was critical of the government’s public relations exercise in the run-up to the general election. “No amount of massaging this through the government portals would convince any objective Kenyan that a good job has been done. On a scale of one to 10, I would put their performance at between three and four,” Lumumba said. The main opposition party, the National Super Alliance (NASA) was a product of the resentment that a majority of Kenyans have for the current regime, he added.

Barrack Muluka, a veteran publishing editor and strategic communications adviser said corruption within Uhuru Kenyatta’s regime has been disguised and sanitised. “Corruption has been practised with impunity. People whose records seem to be very sullied have been rewarded with opportunities,” he told Africa in Fact. In his view, Kenyatta’s government was claiming successes for things it had not actually achieved, such as saying it had “tarred 10,000 km of roads”.

Kenyatta was “staring at defeat” in the next general election, he said.