“Fools say that they learn by experience. I prefer to profit by others’ experience.” ― Otto von Bismarck

Six months have passed since the first COVID-19 vaccine was administered in Coventry, England in December 2020. Since then, 1.5 billion doses have been injected worldwide. The events unfolding in India, however, are a cautionary tale against overconfident leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dire situation there emphasises the fact that we need to remain vigilant during the vaccination rollout.

A timely and effective vaccine rollout remains more important than ever, but it is not a silver bullet in combatting the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 vaccine rollout is the largest immunisation campaign in history. It will require a dramatic mobilisation of healthcare systems for all countries. The United Kingdom (UK), Seychelles, Rwanda and Morocco have impressed the world with the rate at which they were able to administer the vaccine. They provide important lessons in planning and executing such a large immunisation drive.

Waiver of intellectual property rights for COVID-19 vaccines

The biggest challenge facing the COVID-19 vaccine rollouts globally is consistent supply. The situation in India has slowed the supply of vaccines to the global vaccine equity scheme known as COVAX. The Serum Institute of India (SII) was set to deliver its 170th million dose this week but is currently only at 65 million doses. Shortfall numbers are based on delays related to shipments from the SII only. There is currently no timetable to resolve SII-related delays.

At present, much of the African continent is dependent on COVAX and India for vaccine supply. To solve this, South Africa, India and China have proposed a temporary waiver of Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) to allow for generic local manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines. US President Joseph Biden’s administration supported the proposal on 5 May, stating that “extraordinary measures” are needed to end the COVID-19 pandemic. Responses to this announcement have been mixed. Some countries in the European Union (EU) believe it will complicate the production of the vaccine and leave pharmaceutical companies with little incentive to share knowledge and build capacity to produce quality versions of the vaccine. Instead, the EU has offered to provide technical assistance and direct funding from national development agencies to build vaccine manufacturing in Africa capabilities on the continent instead of the proposed patent waiver.

Intellectual property (IP) provides the opportunity for companies to gain market exclusivity and therefore creates an incentive to innovate, especially given the costs and extensive time scales associated with vaccine production. Members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) have an obligation to comply with TRIPS by enforcing IP rights domestically. At an economic level, TRIPS obligations constitute a major obstacle to African countries obtaining sufficient COVID vaccines. These agreements entitle Western pharmaceutical companies to hold the patents on the vaccines, thus giving them exclusivity on the manufacturing and the pricing. Generally, these vaccines were unaffordable for many African states. Taking lessons from the HIV and AIDS epidemic, by linking the COVID-19 pandemic to the security nexus, TRIPS agreements can be overruled on the grounds of “security exceptions” agreed to by the WTO. Thus, it may be advantageous to many developing world countries to securitise the COVID-19 pandemic to fully benefit from the above agreement.

Suspension of the waiver on COVID-19 vaccines is not sufficient, however, to empower countries to locally manufacture generic vaccines. The waiver should apply more broadly to all medical products related to COVID-19. Vaccine manufacturing is more complex than many other pharmaceutical products. Current production capacity of COVID-19 vaccines remains limited and scaling up this capacity will require significant upfront investment and a deft combination of incentives to build sustainable local manufacturing capacity.

‘The vaccine effect’

In the UK, a positive correlation between vaccines administered and reduced hospital admissions, including falling death rates, have been recorded since January. Among the most vaccinated groups, such as the elderly, the sharp downward trend of severe COVID-19 cases indicates a positive vaccine effect and reduces pressure on the scarcest resource of all – ICU beds. The novelty of the COVID-19 virus made the task of developing a vaccine within one year incredibly difficult. Due to the urgency in developing a vaccine, scientists were not adequately knowledgeable regarding its efficacy. Studies and medical advances have demonstrated that vaccines protect individuals from COVID-19 symptoms that could lead to severe illness or death, even if they are slightly less effective at protecting against mild symptoms. John Nkengasong, Director of the African Union’s Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, is urging nations to vaccinate against COVID-19 because “any vaccination is better than no vaccination at all”.

Case studies of COVID-19 vaccine rollout success

United Kingdom

In the UK, vaccination plans began before the COVID-19 pandemic was announced by the World Health Organization (WHO). Scientists at Oxford University met to discuss the development of a vaccine that would repurpose technology used for the Ebola and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreaks. Despite this foresight, the UK would still go on to to have the second largest total number of COVID-19 related deaths (128,0000) in Europe. The B.1.1.7 variant which emerged in the UK became a variant of concern (VOC) in September 2020, and was later shown to be 43-90% more transmissible than the standard strain. This ultimately led to higher incidences and more hospital admissions. But the UK has undoubtedly overcome the worst of the pandemic due to its effective rollout strategy.

Key lessons learnt:

- Secure vaccine supplies due to local vaccine manufacturing as well as imported doses ordered well in advance from suppliers across Europe and in India. 367 million doses, of seven different vaccines, were secured for the population of 67 million.

- Large-scale financial investment ($16 billion) into purchasing, manufacturing and distributing the vaccine.

- Nine specified priority groups across two phases to help accurately identify who to vaccinate first. This also gave the government an estimated demand ratio to match vaccine supply.

- Local supply chain management of the vaccine doses that minimises local storage requirements. Vaccination sites must be ready to inoculate patients as soon as doses are delivered.

- Decentralised vaccination site coverage in three main ways: local GPs and community practices, hospitals, large vaccination sites at various recreational centers. The public can access a list of all these sites online and find out which is closest to their residence by using a postal code search.

Seychelles

The Seychelles, with its relatively small population, has impressed the globe with a fast and effective vaccine rollout, earning the title of the most vaccinated population on the planet. The southern Africa island, one of the most popular tourist destinations off the African continent, has fully vaccinated at least 62% of its population. The government began its vaccination drive with China’s SinoPharm (donated by United Arab Emirates) and Covishield (donated by India), which is a version of AstraZenca produced in India. Although the country did recently experience a rise in cases, the WHO found all the severe cases in those who had yet to be vaccinated. Around 37% of those who tested positive had been fully vaccinated, meaning the vaccinations had reduced the likelihood of severe illness, reducing pressure on ICU capacity.

Key lessons learnt:

- Vaccine diplomacy – the government of Seychelles leveraged its close relations with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to obtain 50,000 doses of SinoPharm.

- Vaccinations were voluntary and free for the public.

- Inoculations took place across a variety of venues, including hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and businesses.

- Front-line workers and the elderly were given priority first and now all residents are able to get their vaccination shot.

Morocco

Morocco has vaccinated more people than any other African country, with 9.8 million doses administered since January 2021. Morocco’s government secured 66 million doses from two suppliers, namely AstraZeneca and SinoPharm, which will be enough to ensure herd immunity for the population. The government also signed an agreement with China to construct a local SinoPharm vaccine factory to help supply its region and the continent with vaccines.

Key lessons learnt:

- More than 3,000 vaccination sites, of which 50% are in remote and rural areas. Another 10,000 mobile vaccinations sites have also been set up.

- Appointments for vaccinations are made by sending your ID number via SMS (for free), which then replies by sending date and place of vaccination appointment. This is effective because no internet connection is required to make an appointment, especially considering the low internet access rates in the country.

- Morocco continues negotiations to procure vaccine supply of SK Bioscience, Johnson & Johnson and Sputnik V to ensure they secure enough doses for their adult population.

- COVID-19 restrictions have remained in place despite its citizens celebrating the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. This was to ensure no surge would take place whilst inoculations were ongoing.

Rwanda

Rwanda was praised for its swift and innovative response to COVID-19 at the start of the outbreak. Their vaccination strategy would follow suit and extensive planning and preparations were put into place before doses arrived. Despite having slowed their inoculation rate due to COVAX shortages, the country is prepared to scale up on daily vaccinations once doses arrive. The government plans to vaccinate 30% of the population (4 million people) by the end of 2021, and 60% by 2022 (8 million people). Rwanda is one among a number of African countries welcoming the temporary suspension of intellectual property rights on COVID-19 vaccines in the US.

Key lessons learned:

- Before the arrival of the first batch of doses, cold chain storage systems were enhanced to a capacity of 300,000 vaccines doses. Within three weeks, over 348,000 people had received their first dose.

- The country has diversified its supply of vaccines. It received 102,960 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, and 50,000 AstraZeneca doses from India.

- Healthcare workers were targeted alongside high risk groups and people aged 65 and above.

- The government plans to develop vaccine manufacturing capacity alongside the African Union’s Partnership for African Vaccine Manufacturing that will ensure a coordinated agenda for the entire continent.

The way forward

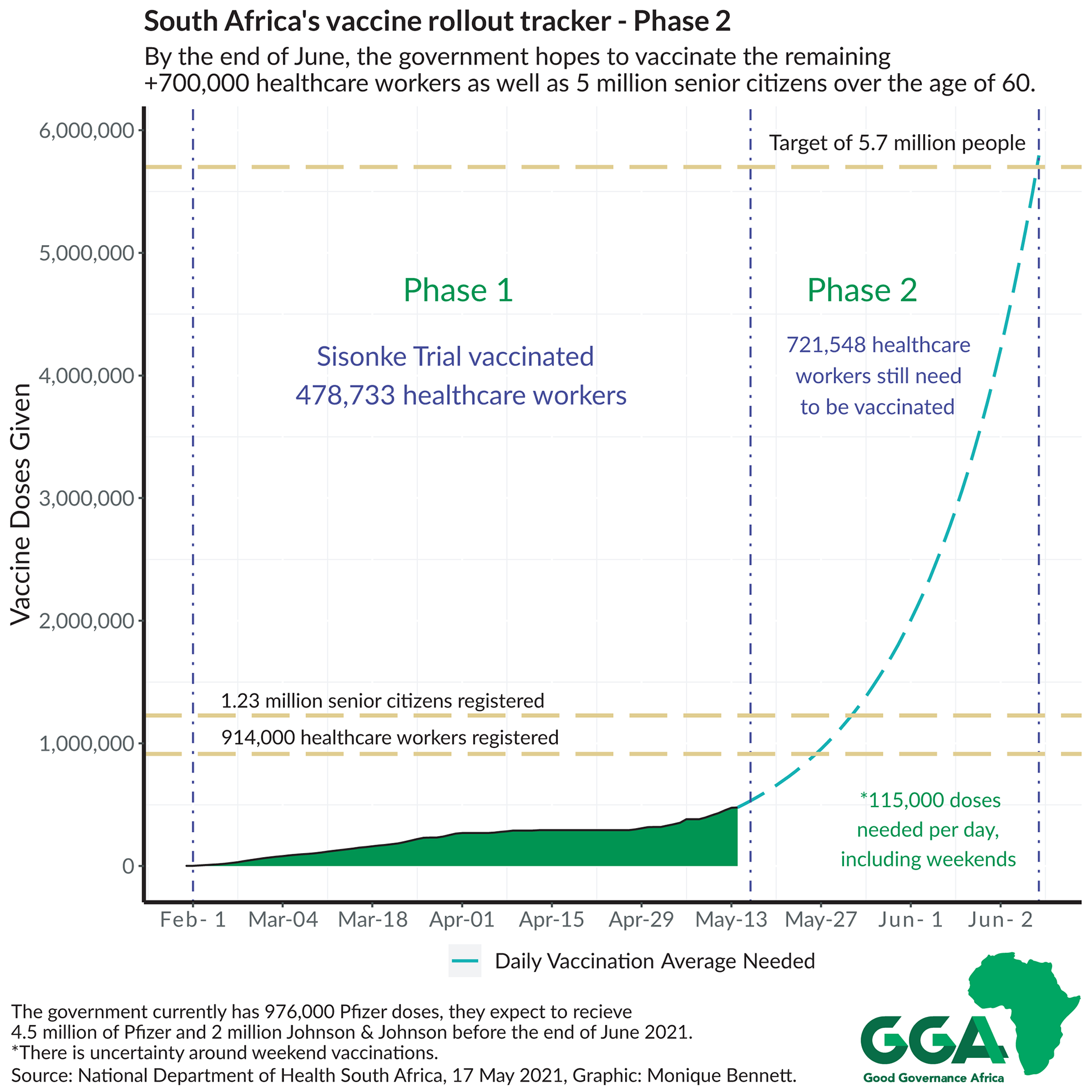

The UK, Seychelles, Morocco and Rwanda provide ample strategy examples for other countries to effectively plan and execute a vaccine rollout. The rollout must be flexible depending on the demand and supply of vaccine doses, but crucially, must have a clear strategy and realistic plan. South Africa’s Phase 2 vaccination plan was launched on Monday (17 May) and expectations are high.

Some of the key lessons for South Africa from the case studies above include:

- Clear and consistent messaging on the inoculation strategy by indicating who gets vaccinated when, with exact timelines.

- The number of Pfizer doses expected in the country by the end of June will fully vaccinate just under 3 million people. If a ‘delayed dose strategy’ is taken, then 5.4 million inoculations are possible with the Pfizer doses alone. This strategy allows for a longer time between first and second dose, to allow for an increased number of people to get inoculated. (A recent study has also shown this delayed timeline to be advantageous to immunity build-up.)

- Decentralise vaccination sites and ensure that public and private sites work together to maximise distribution.

- Increase the speed at which vaccination sites are approved, and allow for flexibility in choosing the sites. Provide mobile vaccination sites for outlying or rural areas.

- Leverage off existing HIV community-based treatment and care structures to administer COVID-19 vaccinations in outlying areas.

- Diversify vaccine procurement to mitigate the risk of supply shortages.

- Maintain strict public healthcare measures to avoid an increased infection rate, specifically leading up to the local elections.

- Electronic Vaccination Data System registration measures should be revised, as the low registration numbers could be indicative of many senior citizens in the registration process (refer to graphic above) not being tech-savvy or falling through cracks in the official communication channels.

- Collaborative initiatives between the state and non-state actors to develop vaccine manufacturing capabilities must be encouraged.