As far as Sino-African researchers are concerned, Africa’s relationship with China is ancient history

In 2002 South Africa’s Parliament unveiled a digital reproduction of a map – of China, the Middle East and Africa – that some speculated could be the first map of the African continent. The Da Ming Hun Yi Tu – the Comprehensive Map of the Great Ming Empire – was drawn up around 1389 during the Ming Dynasty, according to historian Hyunhee Park.

Park published Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds, a book on cartography and the history of contact between China and the Islamic world from 700 to 1500 AD, in 2012. She reveals that Vasco da Gama, the first Westerner to round the Cape, was only able to reach India because his navigator, a Muslim from Gujarat in India, knew the routes.

Park says it was from Arab maps that Chinese cartographers developed their picture of the world, and maps of Africa existed before 1389. China’s relationship with Africa stretches back centuries – as far back as 138 BC says historian Li Anshan, who researches Sino-African relations. Anshan and Park are among very few in this emerging field, disabusing us of notions of China’s supposed ancient isolation.

Anshan writes that indirect knowledge of Africa and trade with Egypt began during the Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD). Trade between China and parts of Africa developed from then and intensified during the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907 AD), when China’s knowledge of Africa came from direct contact with the continent.

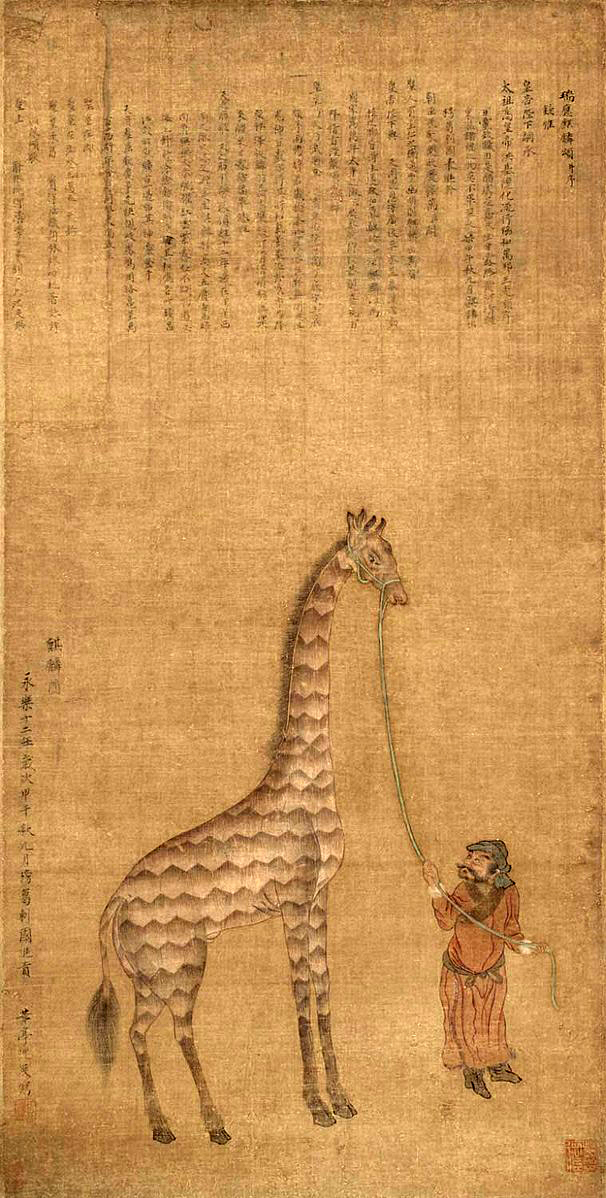

Attendant with giraffe. Artist Shen Du

Contact between Africans and Chinese became more frequent after 900 AD and by the early 14th century, according to historian John Iliffe, “the international trading system stretching from Flanders to China, with Cairo at its core, was breaking down as the Mongol Empire disintegrated in Central Asia, leaving Egypt as a channel through which oriental goods passed to the increasingly dominant economies of Europe”.

In 750 AD the Chinese did not have maps of the Islamic world, which included East Africa, says Park, but by 1500 both regions had produced quite detailed maps of each other’s territories. Both Arab and Chinese maps tended to depict Africa as triangular.

Some of the works of Jia Dan (730-805 AD), a scholarly official who enjoyed studying geography, have been preserved, and these describe a sea route from Guangzhou to the Persian Gulf via East Africa, a journey of six or seven weeks.

Between 1050 and 1150 China’s imports of African goods increased tenfold, according to Iliffe. From the east coast of Africa, ivory was the main export to eventually reach China.

But a more ominous aspect of these exchanges was slavery. Many East Africans were taken to China by Arabs as slaves, and were described by the locals as “devil-slaves”, “wild men”, or “barbarian servants”, according to Anshan, and were treated “like beasts”.

Much of our knowledge of Sino-African relations comes from official Chinese records. A compilation of these was made by the scholar Chang Hsing-lang (1888-1951), titled Communication between Ancient China and Africa, and published in 1962. Archaeological evidence has also brought agreement among scholars. Stone paintings discovered in China in 1979 depict a giraffe. Tang pottery and coins found in Africa present the most direct evidence of Sino-African trade, and Tang clay figurines and paintings of Africans have been found in China.

More than 2000 examples of Tang artefacts were found at an archaeological site in Fustat, a southern suburb of Cairo that had become a centre for politics, commerce and pottery. Other artefacts were found in the Aizhabu port in northern Sudan, and Kenya’s Manda Island. Tang coins have also been unearthed in Zanzibar and Mogadishu.

It was the Mongols’ rule over China, Iran, Baghdad and other regions that made increased contact possible. The Mongols under Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty, which lasted from 1271 to 1368. Their cosmopolitan outlook allowed foreigners to settle in China, and encouraged the Chinese to embark on overseas travels.

One of the earliest accounts of these journeys was written by Wang Dayuan (1311-1350). He went on two expeditions, from 1330 to 1334 and 1337 to 1339, to reach Malindi in Kenya, Kilwa Kisiwani in Tanzania, and possibly Mozambique – though some Chinese scholars have expressed scepticism about the last location. He produced a narrative based on extensive travel and information collected from first-hand interviews, called the Shortened Account of the Non-Chinese Island Peoples.

At almost the same time, but in the opposite direction, Ibn Battuta of Tangiers, Morocco, set out on his travels in 1325, a year after Marco Polo had died. He set his experiences down in The Travels of Ibn Battuta.

Travelling through the cities of Asia Minor (Turkey), he then crossed the Black Sea and there encountered the Great Horde, the Mongols. Arriving at the port city of Ts’wan-chow-fu, known as Zaitun to the Muslims, he saw about 100 large junks and numerous smaller ones, and judged that Zaitun was the largest harbour in the world. Ibn Battuta saw much of the country, journeying from one trading post to the next, including Canton, before reaching Beijing, then known as Khanbaliq, the capital established by the Mongols.

His sensibilities made him anxious about the plight of Muslims in China, and he worried that they might not be free to practise their religion. “For all its magnificence, it did not please me,” he said of China. “I was deeply depressed by the prevalence of infidelity and when I left my lodging I saw many offensive things which distressed me …”.

He was overjoyed when he met a Muslim jurist from a town neighbouring his in Morocco – a chance meeting that attests to the frequency of journeys to China.

A little later, the well-known expeditions of the eunuch Zheng He (1371-1435) give us a sense of the scale of Chinese diplomacy. Zheng He, a mariner and diplomat during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), made seven expeditions to Africa from 1405 to 1433. In all, he led a fleet of 62 nine-mast treasure ships across the Indian Ocean, “each as large as a sizable village, and nearly two-hundred smaller vessels”, according to the testimony of his translator, Ma Huan.

Zheng arrived in Kenya on the East African coast in 1418, and met the Sultan of Malindi. But officials of the military department destroyed records of his travels in 1480 to discourage eunuchs from repeating Zheng He’s success as part of a rivalry between officials and the eunuch clique favoured by the deposed emperor.

These were mostly fleeting encounters undertaken for reasons of diplomacy and trade, and evidence of Chinese settling in Africa only begins later. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), in 1654, three Chinese were taken from Batavia (now Jakarta) in Indonesia to settle in Mauritius. In 1660 Wang Shou, a prisoner of the Dutch East India Company, was shipped to the Cape of Good Hope.

Chinese emigrated to East Africa in large numbers during the colonial period. Between 1850 and 1875, as many as 1,3 million Chinese arrived in colonies to work as indentured labourers, with a further 750,000 moving abroad to all parts of Africa over the next 25 years. These immigrants often became citizens of these countries, except when they were repatriated, as occurred in South Africa in the first decades of the 20th century, when pressure from white electorates in the Transvaal and the Cape introduced laws to prohibit or restrict Chinese immigration.

These early exchanges will be fleshed out as historians re-examine the history of globalisation, which we have been told began with the colonisation that the West initiated. From these encounters, we know that globalisation is a complex and many-sided process that distributes ideas, bodies, wealth and even poverty in an uneven and ever-contested terrain.