Political instability and unclear policies rock Egypt’s bourse

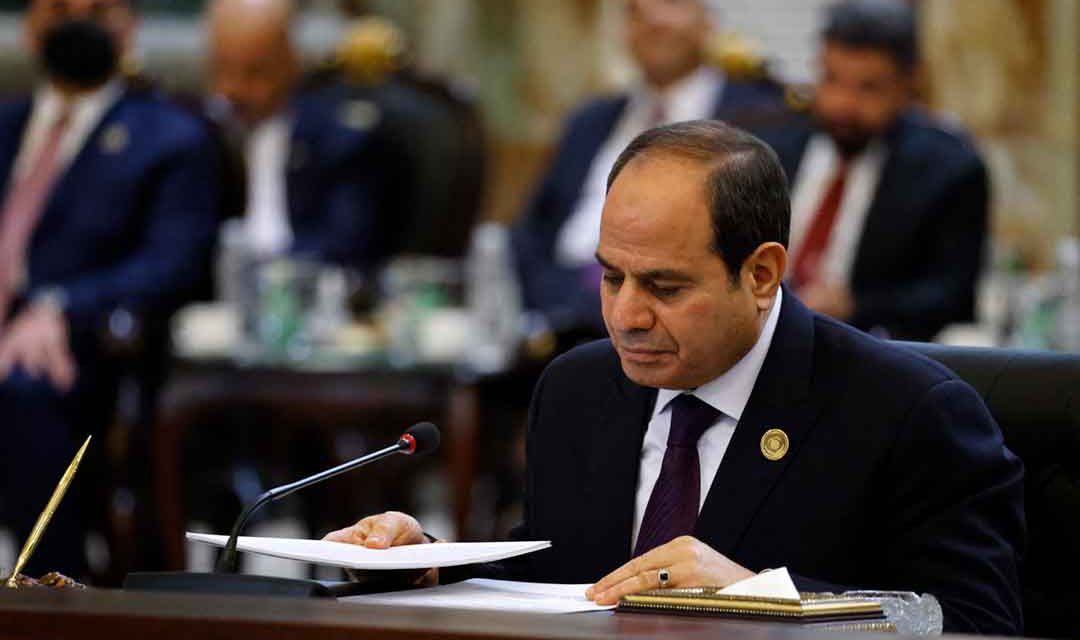

Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi © Kremlin

By Kristen McTighe

In the aftermath of the 2013 military coup that toppled Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s former Islamist president, more than 1,000 anti-government protesters were killed, thousands more jailed and hundreds sentenced to death. A government crackdown on dissent sparked international condemnation. Militant attacks became routine and at least 600 security personnel were killed as the army and government struggled to restore security. The country’s economy, ravaged by years of unrest, was slow to improve, providing little economic relief for most of the country’s 90m citizens. Yet, paradoxically, its bourse began to boom. Between July 2013 and December 2014, the Egyptian MSCI index, a measure of large and midsize market segments, nearly doubled, producing a total return including dividends and share price rises of more than 30%. As a result, the Financial Times named Egypt the best destination for stock market investors in 2015. The accolade marked a change in fortune for Egypt, which was hard hit by the 2011 revolution that ended three decades of rule by autocrat Hosni Mubarak. Persistent unrest after Mr Mubarak’s removal battered important sectors of Egypt’s economy, such as tourism.

Foreign investment declined and financial markets suffered huge losses. Unfortunately, matters did not improve under Mr Mubarak’s successor, the democratically elected Mr Morsi. Critics accused Mr Morsi of lacking a coherent economic strategy and failing to make much-needed reforms. With political instability continuing throughout his rule, frustration over the deteriorating economic situation fuelled the protests that culminated in the military removing him in July 2013. Then in late 2013, the Egyptian stock market — with a market capitalisation of 365 billion Egyptian pounds ($53.2 billion) — began to make headlines, thanks to a perceived increase in political stability. “The strong recovery in the second half of 2013 and first half of 2014 was a kind of relief, from the market point of view, that instability was over,” says Simon Kitchen, director of Middle East and north Africa strategy at EFG Hermes, an investment bank. “When Morsi was overthrown, it was pretty clear that there would be a sort of restoration, and so that gave the stock market a deal of certainty.” Financial aid from Gulf countries also buoyed investors’ optimism about Egypt’s direction, Mr Kitchen said.

The resolution of long-running disputes between foreigners and the Egyptian government — such as the repayment of $1.5 billion of the $6.4 billion Egypt owed foreign gas companies — helped too. Moves to ease the repatriation of money by foreigners, which had been implemented after the 2011 revolution, also pleased investors. New president Abdel-Fattah al- Sisi’s bold moves to reform the budget, including cutting energy subsidies, buoyed the market further and emphatically demonstrated Mr Sisi’s control of the country. “Partly because of the removal of Morsi and the end of a year of very bad economic management, there was initially a lot of hope things would get better,” says Angus Blair, president of the Signet Institute, a Cairo-based economic think-tank. “And because of capital controls, it meant the money had to go somewhere, so it went into real estate, high-end goods and, of course, the stock market.” The portents were so good that in April this year, Mohamed Omran, chair of the EGX30, an index of the top 30 companies on the Cairo and Alexandria exchanges, announced that the bourse had raised 4 billion pounds (about $511m) in the first quarter of 2015 for six companies, twice the 1.9 billion pounds ($243m) raised in 13 initial public offerings in 2014.

“Egypt has seen a renaissance in listings this year,” confirms Moustafa Bassiouny, an economist at Inktank Communications, a Cairo-based investor relations agency. To reinforce the trend and reinvigorate trading in Egypt, the EGX30 announced in late May that it would reduce the minimum free float (the number of a company’s shares that are available for trade) required for new companies to be added to the top-30 list. But despite the hype over the Egyptian exchange in Mr Sisi’s first year, the index fell by 2.2% by June, and daily volumes were still well below their 2010 levels of $180m. That same month, the Egyptian bourse overtook Colombia as the world’s worst-performing exchange. Experts said a combination of domestic and international factors was behind the downturn of the Egyptian bourse. The surge in investor confidence that followed the 2013 military coup could no longer propel the market. “Internationally, investors are shying away from emerging markets, where growth is slowing down on the back of lower commodity prices, geopolitical risk and the financial situation,” Mr Bassiouny explained. “That, coupled with unresolved issues in Greece, is having an impact on the Egyptian market.”

In July this year the International Monetary Fund projected growth in emerging market and developing economies to slow from 4.6% in 2014 to 4.2% in 2015. As the surge in investor confidence that followed the coup levelled out, domestic issues, many of them longstanding, also contributed to the stock market’s decline. These included “concerns of dollar shortage and capital controls, then the legislative overhang… and, to some extent, concerns over risks from the security situation”, Mr Bassiouny said. “All of this adds some measure of ambiguity to the market.” But the government could still reinvigorate the market. “The Egyptian exchange is a private vehicle, but what the government could do is address the macroeconomic issues, introduce reforms in the economy, tackle monopolies, bring down inflation, supply more energy, cut bureaucracy, get a real economic vision,” Signet’s Mr Blair said. The government’s inability to delineate a clear economic policy has also made investors wary. “At the end of June, the central bank began to let the currency weaken and they gave very good reasons,” Mr Kitchen said. “Then it stopped a little over a week afterwards, and people don’t quite understand why.

[investors] understand why and what the outcome for the currency is, they will be reluctant to invest and if they are reluctant to invest, the stock market isn’t going to do well.” Despite the decline, some remain optimistic. “The picture is looking good going forward,” Mr Bassiouny said. “We are seeing a direct play on the demographic fundamentals of the Egyptian economy with a focus on consumer stocks that seek to benefit from the country’s young, growing population and the proportionately large and comparatively inelastic expenditure on food and healthcare.” Beyond all else, the security situation could still pose a challenge to the long-term success of the Egyptian exchange. At the end of June the country’s top prosecutor, Hisham Barakat, was assassinated in the highest-level political killing since 1990. Two days later militants aligned with the Islamic State nearly overran a town in the country’s restive Sinai Peninsula, followed by the bombing of the Italian consulate in Cairo a week later. The wave of violence has led to questions about the government’s security policies and sparked concerns that Mr Sisi is losing control. “Right now there is a sort of base level of violence that investors have gotten used to and they are more interested in economic issues like tax rates and the currency,” Mr Kitchen says. “But if you keep seeing car bombs in the capital, they become more pessimistic.”