Indian prime minister Narendra Modi © www,pmindia.gov

East and Southern Africa’s sizeable Indian diaspora won’t necessarily cement the country’s ties with the continent, but careful diplomacy might

In July 2016 Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made his first official visit to Africa. The visit was seen as a follow up to, the 3rd India-Africa Forum Summit (IAFS), which took place in New Delhi nine months before, and which African and Indian media and commentators agreed had been successful. The IAFS had been identified as a significant platform for the Indian leader to strengthen India’s ties with the continent.

Modi’s itinerary focused on four countries in the Eastern and Southern African region, namely: Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania and South Africa. Each of these regions is home to a significant Indian diasporic community, with South Africa accounting for the largest number of South Asians living in either.

Labelled as “Modi’s African Safari”, the visit was characterised as a defining moment in India’s Africa policy. It is seen as cementing India’s footprint in the East and Southern African regions and as signifying a new “Strategic Partnership in the 21st Century” between India and Africa. But more carefully considered, it shows a possible alignment of Modi’s foreign policy with India’s geo-economic interests.

Modi’s Africa tour has been greeted with predictable hype, as well as questions concerning its likely outcomes. The pertinent policy question is whether Modi’s charm offensive has successfully defined an Africa policy for New Delhi.

It would seem that India’s approach to its African relations is defined through the framework of identifying “anchor” states or “gateway” countries through which it might advance its regional economic and commercial interests. Modi’s visits to Mozambique, Kenya, South Africa and Tanzania can be seen in this light.

But, India also has a close historical affinity with South Africa. During Modi’s visit to South Africa, he paid respects to Mahatma Gandhi, whose career began in South Africa, and interacted with members of the Indian diaspora. India and South Africa also consider themselves to be natural allies. Each has fought for independence from minority domination, pursue non-alignment and advocated for a just, equitable, and inclusive global system that reflects current structures of political and economic power.

Moreover, both countries are seen to be like-minded partners in BRICS and IBSA—though there have been tensions of late, relating to South Africa’s ambivalence in supporting India’s entry to the Nuclear Supplier Group, which seeks to limit the proliferation of weapon-related nuclear technology.

But did Modi’s visit result in a more entrenched Africa focus in India’s foreign policy agenda? Chris Alden, professor of international relations based at the London School of Economics, argues that “the political imprint is what has been missing or at least neglected in the engagement so far … the driving force of Indian business in defining the relationship has meant that political considerations have been less prominent, as witnessed by the various conclaves held on India-Africa relations.”

Modi has consciously intertwined India’s commercial interests through the “Make In India” framework—a Modi government flagship programme aimed at transforming India into a global design and manufacturing hub—and diplomacy in the sub-continent, the Asian region and beyond, Alden argues, adding that the Indian diaspora has also been important in extending the country’s influence in Africa. But Africa’s real positioning in Modi’s geo-economic charm offensive remains a static arena when it comes to New Delhi’s global hierarchy of interests.

No formal policy paper defines India’s political and economic orientation in Africa. What is clear is that Modi’s geo-economic orientation as regards India’s foreign policy provides some impetus for embedding a more expansive economic diplomacy in New Delhi’s foreign policy engagements. Africa is no exception to this approach.

Tellingly, Modi’s African safari represented a degree of geo-strategic overlap with China’s footprint in the region. Modi also visited Mauritius and Seychelles, signalling India’s aim to counteract China’s largesse in the Indian Ocean Rim and Beijing’s extension into the East African and Horn of Africa through the One Belt One Road development policy, launched in 2013. The calculus is simple: India wants to extend its influence in the Indian Ocean Rim. An emboldened China is operating in the region, which India considers as its sphere of influence.

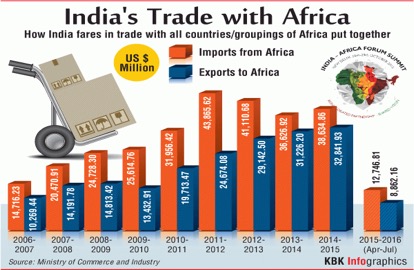

“The Chinese footprint in Africa, when coupled [with] the less publicised pressures to Indian interests on its borders and in the sub-continent, may refocus the sharp eye of geopolitics on Africa and, through that, bring about a more conscious melding of political and economic interests,” Alden suggests. However, this may take some time to materialise, given that India’s trade and investment profile with the continent is still negligible in comparison to China’s economic engagement, as indicated in the chart.

Clearly, India’s trade with Africa is dwarfed by that of China. But New Delhi could choose to remain quietly under Beijing’s shadow, while using a “behind the scenes” approach to embed its footprint across Africa. It does appear that under Modi, India is positioned itself to become an aggressive economic actor by pursuing an assertive economic diplomacy strategy.

So what does this mean for the future of India-Africa relations?

It seems that even though Modi’s visit to the four African countries appeared to be last on his agenda, there have been attempts to make the engagement more pragmatic. “Under the Modi government, India- Africa relations have been reinvigorated and further aligned with the development priorities of countries in Africa, more specifically, Agenda 2063 of the Africa Union (AU), and the broader 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by the UN General Assembly, with a specific emphasis on financing for development,” Says Renu Modi, a senior lecturer and former director of the Centre for African studies based at the University of Mumbai.

At the most recent edition of IAS, in October 2015, India sidestepped the Banjul Formula, which limits India’s interactions with African countries, and made a concerted effort to include all the continent’s countries. This signals a new trajectory in India’s Africa focus, as compared to the previous Indian National Congress-led government. The more expansive approach to IAFS indicates that Modi does not want to take a cautious approach to New Delhi’s Africa Policy.

Instead, Modi wants to be able to draw on a wider set of engagements that will bring credibility to India’s political, economic and social engagements and enable the Asian counry to be seen as pragmatic partner in Africa’s development agenda. In some quarters this is seen as an attempt to gain leverage and support from the African bloc in the UN around New Delhi’s aspiration for a permanent seat at a reformed UNSC. But others say that Modi’s African engagements are also a way to disrupt China’s African footprint on the continent.

Either way, India must understand that the African landscape is not an easy terrain to traverse, given the complexities of the geo-strategic interests that underline continental politics. African governments could for instance, seek to play the one Asian giant against the other. India would do well to be aware that a one-size-fits-all approach to its Africa policy may not be the appropriate.

A more pertinent approach would be to identify and engage with African Regional Economic Communities (RECs), given that each of these RECs aims to provide an enabling environment for trade, investment and development cooperation. The RECs serve as a foundation for continental frameworks such as Agenda 2030 and Agenda 2063. India could expand on its policy of “gateway” countries by identifying regional policy programmes. This could then feed into a broader continental strategy for India’s Africa focus.

Has Modi’s charm offensive begun to push for a more pragmatic engagement with Africa? This question can only be answered in 2020, when the next IFAS takes place.