Desert locusts at a maize field in Meru, Kenya. February 2021. The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation works with a variety of Kenyan security, logistics and charter companies who have expanded their operations to closely track swarms of locusts in East Africa, before dispatching teams to targeted areas to spray the insects with pesticides to prevent damage to crops and grazing areas. It has been over a year since the worst desert locust infestation in decades hit the region, and while another wave of the insects is spreading through Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya, the use of cutting edge technology and improved co-ordination is helping to crush the ravenous swarms and protect the livelihoods of thousands of farmers. Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP

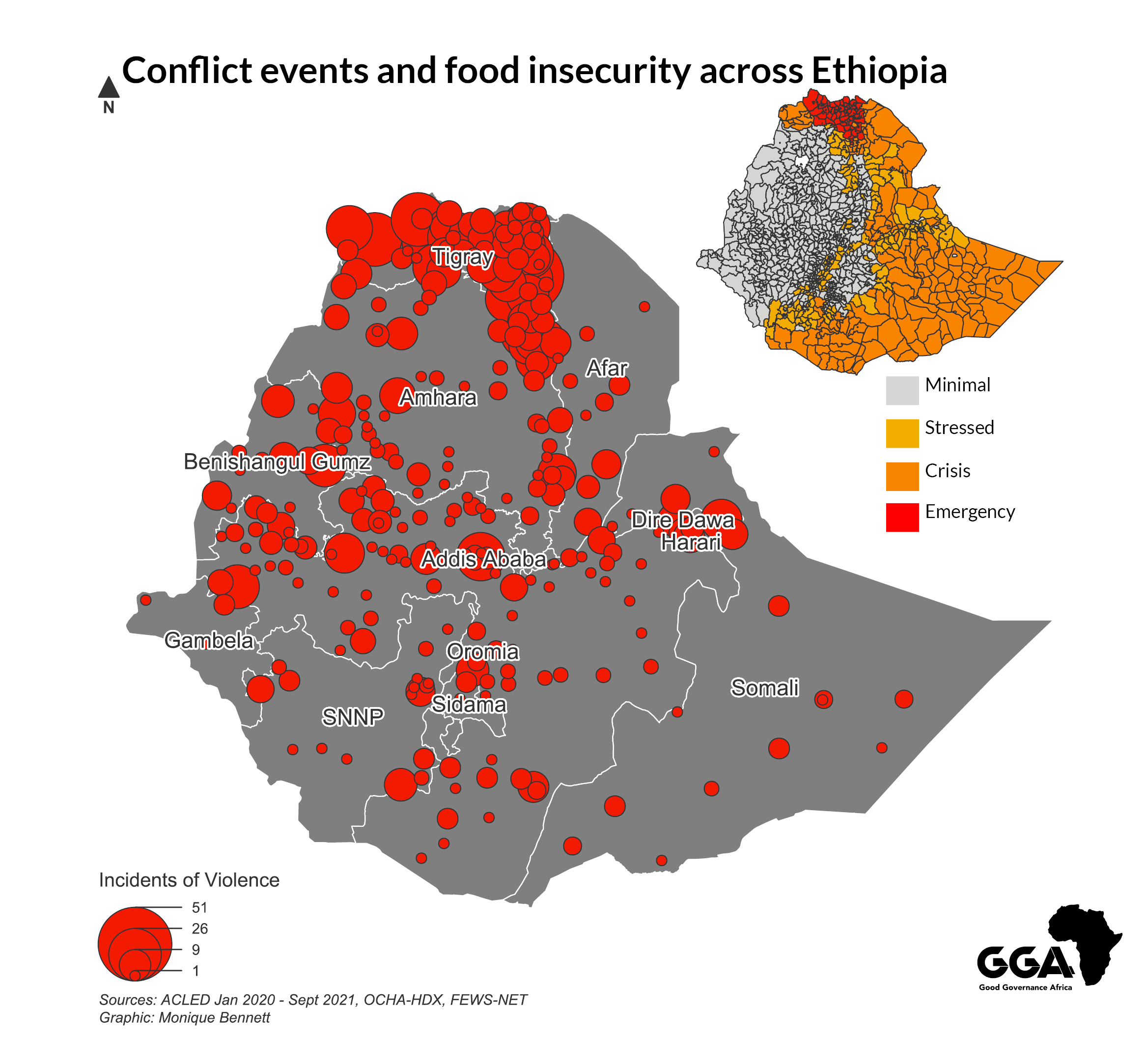

In 2020, East Africa experienced its worst desert locust outbreak in 25 years — in 70 years for Kenya — which put nearly 40 million people at risk of food insecurity. Now, there is a new warning of desert locust hopper bands breeding in the northeast of Ethiopia, an area that cannot be easily accessed because of ongoing insecurity.

Before the insecurity in northern Ethiopia began in November 2020, the population was already battling climate shocks as well as the worst desert locust infestation for decades. The region was also home to nearly 50,000 Eritrean refugees whose camps have since been either destroyed or severely damaged by the conflict.

The conflict in Tigray took a stunning turn at the end of June 2021 when Tigrayan forces retook the capital, Mekelle, after federal forces withdrew soldiers and declared a ceasefire. The federal forces have since allied with regional leaders from Afar and Amhara to help mobilise soldiers to join the conflict.

With that, the conflict has entered a new phase and expanded its borders into neighbouring Amhara and Afar, where more than 76,000 people have been displaced and 300,000 have fled since mid-July.

Adjacent to the Tigray conflict, the land dispute conflict between Afar and Issa tribes continues. This insecurity puts at least 5.1 million people at risk of acute food insecurity.

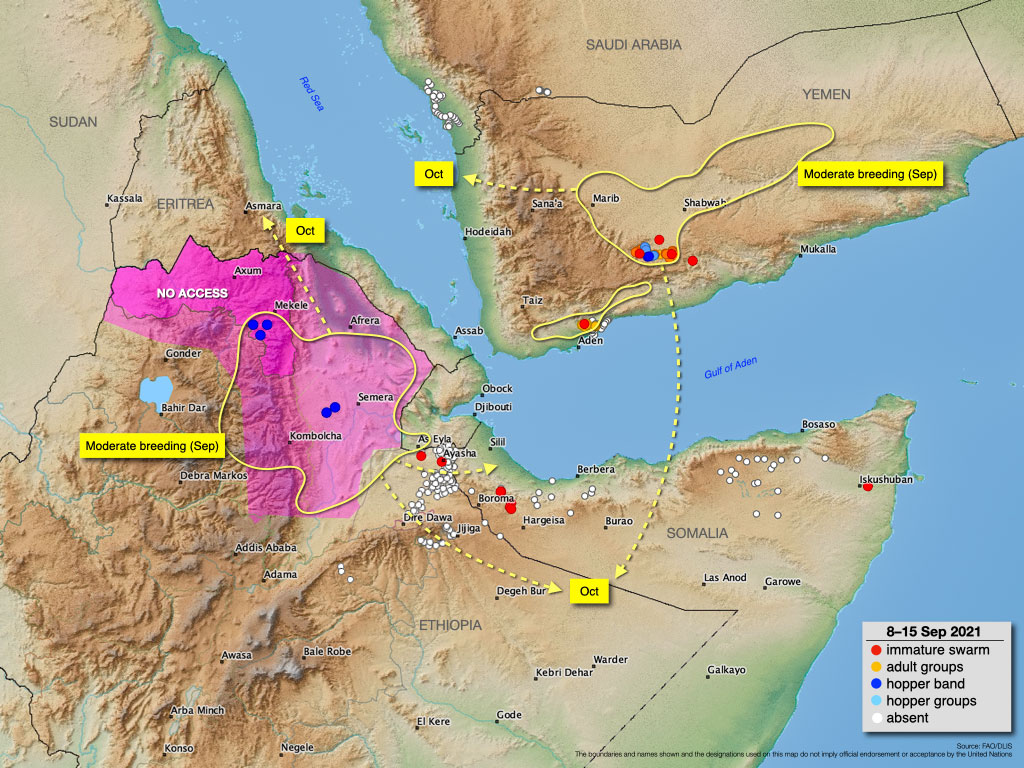

Now, there is warning of desert locust hopper bands breeding in the northeast of Ethiopia. Desert locusts decimate crops. These areas cannot be accessed by desert locust control teams due to the insecurity. Swarms are likely to form towards the end of September and continue into October. They are likely to migrate into Eritrea and eastwards into Somalia.

Absence of data from the Afar region makes it difficult to predict the scale of breeding and potential migration. For a region already in dire straits, another surge of desert locust swarms could be a fatal blow for farmers who have recently sown crops for the new season as well the civilian population.

An outbreak of biblical proportions

In 2020, East Africa experienced its worst desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) outbreak in 25 years (in 70 years for Kenya), which put nearly 40 million people at risk of food insecurity. The warming of the Indian Ocean, caused by anthropogenic heat, has helped increase the frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones, creating favourable conditions for desert locust breeding and mutation.

Desert locusts have been a primary enemy for African and Asian farmers since Pharaonic times, but due to their natural oscillation between recission and resurgence, control operations lack consistent financial and state support. The outbreak came at a time when the Covid-19 pandemic forced the affected countries into lockdowns, restricting the supply of essential equipment as well as control operations. Despite early warnings from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Locust Watch, countries were not sufficiently prepared for the scale of last year’s outbreak.

Although the upsurge has yet to reach the same scale as last year, conflict in Yemen and parts of northern Ethiopia presents a serious threat to effective control operations. The Acting Humanitarian Coordinator for Ethiopia, Grant Leaity, recently released a statement detailing the urgent need for unimpeded humanitarian assistance for at least 5.2 million people across the northern region. Famine-like conditions are being experienced by nearly half a million people, while 5.5 million are facing acute levels of food insecurity, according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC).

Now and then: control operation efforts since the outbreak began

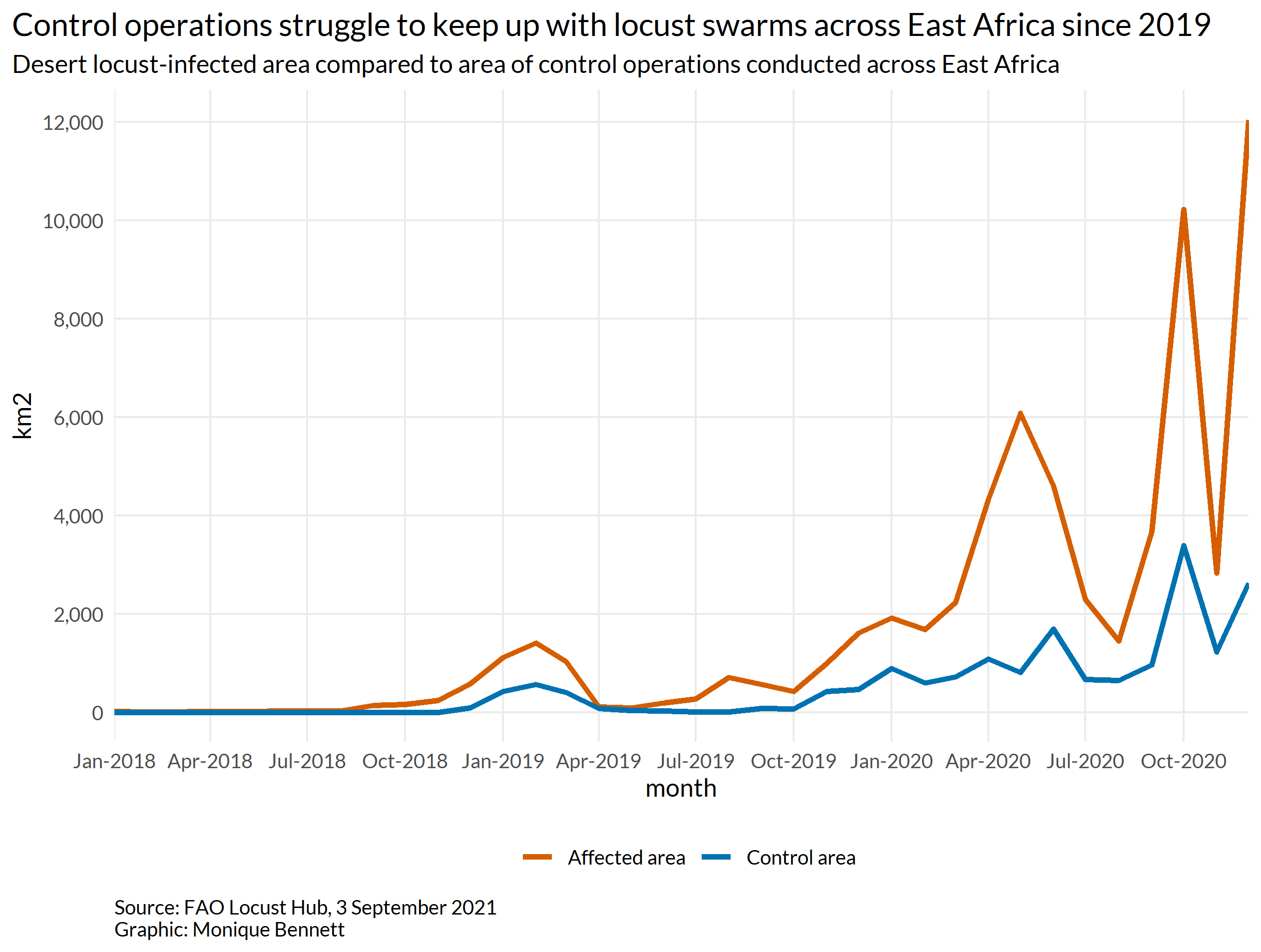

Throughout 2020, control operations battled to keep up with the surge of locusts due to lack of resources and overall control capacity coupled with COVID-19 restrictions. A desert locust impact assessment by the Food Security and Nutrition Working Group, regional platform of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (Igad), estimated that one in three respondents living in desert locust-affected areas in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and Uganda had experienced pasture and/or crop loss due to the outbreak.

Ethiopian respondents recorded the most losses and were found to have the highest prevalence of food insecurity since the desert locust outbreak began. The most commonly reported desert locust-related impacts experienced by respondents included malnutrition/food insecurity, emotional stress and human and animal health issues.

Ethiopian and Somalian respondents were the most pessimistic when discussing the prospects of agricultural production for the remainder of the year. A majority thought that their production would be well below average this year, mostly due to the locust outbreak and poor rainfall. This assessment was conducted before the conflict in Tigray began. Therefore, concerns over insecurity would likely be included now as a factor hindering the production of livelihoods for Ethiopians across the northern region.

As mentioned before, at the time of the outbreak, regional bodies like the Desert Locust Control Organisation for Eastern Africa (DLCO-EA) lacked the necessary resources to cope with the extent of the outbreak across East Africa. Despite early warnings, the DLCO-EA and member states did not have sufficient supplies of pesticides, protective gear and control teams to effectively prepare and deploy control operation teams.

The FAO responded to this shortfall by providing technical and operational assistance in partnership with Igad, the Emergency Centre for Transboundary Plant Pests and the Regional Desert Locust Alliance (RDLA) (the RDLA was formed in February 2020 and comprises more than 60 national and international non-government organisations).

Surveillance has improved significantly since the start of the outbreak with the introduction of upgraded tools for both data collection and transmission, like the eLocust3m application and Garmin’s eLocust3g GPS. These upgraded technologies have helped record and send live survey and control data from the field to national locust centres to help plan and prioritise operations.

In June, Igad launched the Hazards Watch for East Africa, the first of its kind developed on the African continent, that combines satellite technology, open-source programming, earth sciences and design to help monitor extreme events and climate hazards for better decision-making.

Funding remained a significant factor hindering initial control operations across East Africa at the start of the outbreak. Since then, the FAO secured $152-million, but a shortfall of $11.2-million remains. This shortfall is mainly within the surveillance aspect of the operations, which is already challenged by difficult terrain, remote locations and conflict insecurity.

Cooperation between the DLCO-EA member states and regional environmental centres was initially weak, but has improved significantly since 2019. Collaboration at regional and national levels has been seen through regular Igad ministerial conferences to fine-tune the findings of assessments and to develop actionable recommendations to improve preparedness to respond to current and future desert locust outbreaks.

While international organisations play an important role in supporting locust control planning and execution, upscaling the capacity of local and national centres remains a crucial challenge.

Loss of crop and animal feed livelihoods is the greatest risk posed by desert locust invasions. The FAO has continued to take an early recovery approach to help safeguard these livelihoods which, in Ethiopia, make up 80% of the population’s income. These communities are highly sensitive to climate variability and are disproportionately affected by natural disasters.

In partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the FAO supported almost 100,000 households with livelihood inputs, equipment for control operations as well as cash throughout 2020 until February 2021. The African Development Bank, European Union, USAID and the World Bank have contributed a combined $544-million since the start of 2020 to assist in resource mobilisation against the locust outbreak.

The locusts are not done yet and the conflict continues — what next?

The latest bulletin from the Locust Watch indicates hopper bands forming in Amhara and that swarms were spotted in the Tigray capital of Mekelle. Forecasts suggest that hopper bands are forming in Afar but breeding areas are inaccessible due to the conflict.

The current insecurity across the northern region of Ethiopia does not allow for control or survey operations. This will allow for summer-bred swarms to mature and lay eggs once the rains begin in October and November, allowing for a new generation of swarms before the end of the year. These new swarms would affect Eritrea, the Somali region of Ethiopia, northern Somalia and Djibouti.

To prevent further humanitarian destruction and worsening food insecurity, the following recommendations are listed below:

- Dialogue between actors aimed at allowing for safe passage, as soon as possible, should be the primary priority. Safe access via ground and air to the identified locust breeding areas to allow for control teams to operate in both surveying the area and controlling for premature hopper bands must be the primary goal of all stakeholders;

- The FAO in partnership with Igad, DLCO-EA and the RDLA should be included in dialogue with the Ethiopian national government, Tigray Defence Force leadership where possible and the regional governments in Amhara and Afar;

- Continue training and knowledge dissemination to assist in preparing communities that may be affected by the predicted upsurge;

- Secure adequate resources to ensure an early response to livelihood losses across the communities predicted to be affected; and

- The FAO, DLCO-EA and its regional partners should provide an updated assessment on funding and resources needed to control the impending outbreak and its consequences.

This article first appeared in the Daily Maverick on 27 September 2021