A nexus between power, politics and the military

Literature is awash with research on the militarisation of the state, especially in West Africa, the Middle East and Latin America, where military involvement in politics is relatively common.

Militarisation of the state has been a common problem in post-independence Africa as countries attempt the democratisation process. A common occurrence has been the hijacking of democratic transitions which have then morphed into largely dictatorial forms of governance, popularly referred to as “hybrid regimes”, whose main characteristic is a mixture of lip service to liberal democracy and a modicum of official representativeness and respect for civil and political liberties, but with fundamentally intolerant dictatorial tendencies and traits.

Members of the Zimbabwe National Army run in formation during \defence Force Day celebrations held at the National Sports Stadium in Harare on 14 August, 2018. Photo: Jekesai Njikizana/AFP

The debate continues as to whether Zimbabwe is a militarised state or not. Some scholars, such as Godfrey Maringira, Tyanai Masiya, Enock Ndawana, Martin Rupiya and Blessing Miles Tendi, have argued that the lack of military professionalism and the concomitant militarisation of the country has had a negative effect on development as well as in stifling the choice, will and participation of citizens in the selection of political leaders. Maringira and Masiya (2017) contend that the military should not play any role in politics. They argue that if it is allowed to participate, especially in electoral processes, “it is likely to defend the regime that serves military interests rather than the interests of the voters”.

Rupiya (2003) argues that the involvement of the military in politics is not only unprofessional but should be frowned upon, as it is a threat to the security of the people. However, other scholars such as Alfred Stepan, Imad Harb and Samuel Finer argue that there is an overarching reason why the military should be involved in politics.

In the Middle East, for example, the military has always maintained that politics is too important to be left to civilians. In fact, Finer (1974) argues that the military is quite disciplined and so can be trusted to take over political power and thus should be an actor in politics, while Harb (2003) contends that military disengagement from politics should never be final and complete. In the Brazilian context, Stepan argues that the military has a political function.

This article grapples with whether the role of the military in Zimbabwe is in violation of Section 208(2) of the Constitution. It also considers whether this military involvement has in any way harmed good public policy, the developmental needs and concerns of the country, as well as whether it has taken away the electorate’s ability to hold government to account on an ongoing basis.

Militarisation is a multifaceted process that includes the following main elements: the dominance of military virtues and ethos; the rise in military spending and proliferation of materiel; significant military control over government programmes or retention of power itself; the preponderance of military solutions to every security problem and the penchant to resort to the use of force or the threat to use it.

Militarisation can either be covert or overt, as military personnel may not assume a publicly leading role in the political sphere, but rather use their firm control over the office holders of power to penetrate state structures such as the management of certain key sectors.

However, militarisation in some contexts is synonymous with the military overstepping its professional domain and entering the political space uninvited and usually in the form of a military coup.

Militarisation of the state is usually driven by numerous factors but mainly used as a form of coercion by governing elites to contain a restive population in cases of a crisis in legitimacy or a loss of hegemony, as well as the need to control vested economic interests. A crisis in legitimacy is usually caused by the ruling elite’s failure to address issues of poverty, illiteracy and disease.

In Africa, militarisation is inextricably linked to the continent’s chequered history of imperialism in which both colonial and post-colonial governments were largely authoritarian in nature and relied heavily on coercion to govern.

Furthermore, most post-colonial governments in Africa were born out of politico-military organisations who waged armed struggles to attain independence. Thus, the military is intrinsically part of the governing elite, given that most of their leadership participated in the liberation struggles and share the same ideologies, especially that of anti-imperialism and nationalism.

Militarisation has manifested itself in various forms in Africa, resulting in the continent recording more than 200 coup incidents between 1960 and 2020 of which 81 were successful. Civil wars have not spared Africa either, resulting in militarisation and thereby negatively affecting democratic development, leading to negative socio-economic development and human insecurity. In fact, the military has largely assumed the role of the supervisor, moderator or arbitrator of the democratisation process, especially in countries such as Egypt and Sudan.

In Zimbabwe, the outbreak of the Matabeleland conflict in the early 1980s marked the genesis of the military’s involvement in local politics, firstly as a deployment to the largely ethnic conflict in the southern and western regions of the country. Secondly, the military, over the years, accumulated the highest concentration of highly educated and qualified professionals, whose expertise was required in other sectors within government. This is because as part of its human capital development policy, the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) encouraged its personnel to further their education, partly because they had abandoned school to join the liberation struggle.

To demonstrate this, currently the military has the highest concentration of personnel holding Doctoral (PhD) qualifications. More so, it established its own dedicated university, the Zimbabwe National Defence University (ZNDU).

The government adopted a deliberate policy of appointing individuals with liberation war credentials and high-ranking security backgrounds to senior posts in civilian state institutions. Importantly, these appointments were not limited to members of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) but also applied to the broad spectrum of the country’s security services.

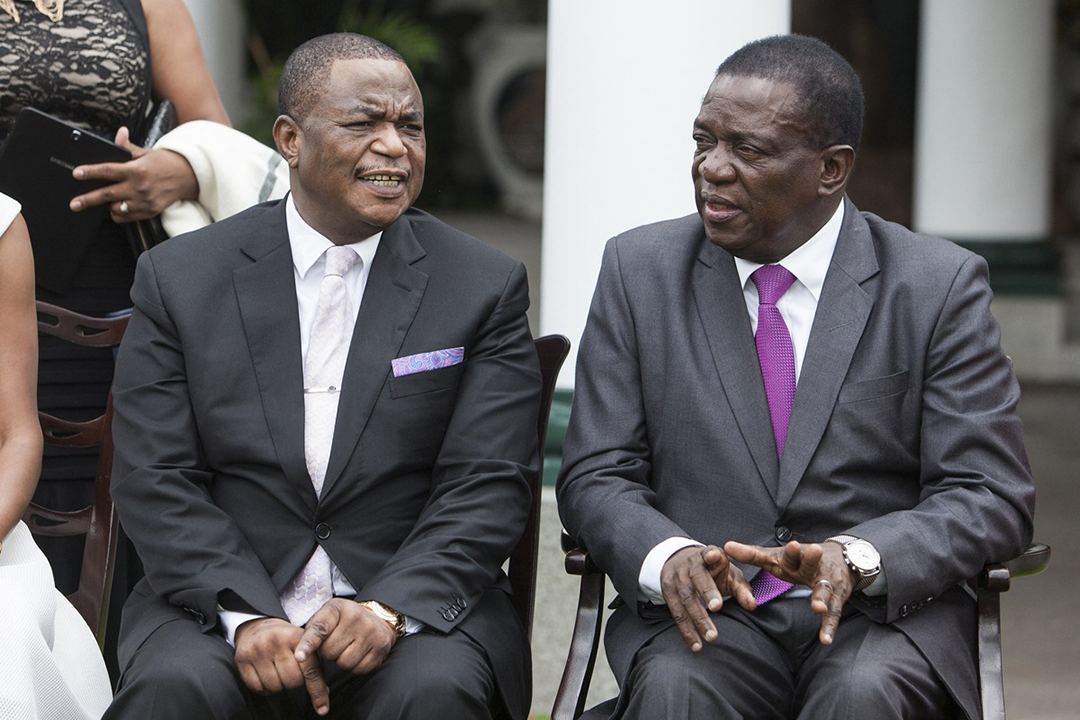

Zimbabwe’s former Army commander and newly appointed vice- president General Constantino Chiwenga (L), and Zimbabwe’s president, Emmerson Mnangagwa (R), sit and talk as they attend their swearing-in ceremony in Harare, on 28 December, 2017. Photo: Wilfred Kajese / AFP

Zimbabwe’s former Army commander and newly appointed vice- president General Constantino Chiwenga (L), and Zimbabwe’s president, Emmerson Mnangagwa (R), sit and talk as they attend their swearing-in ceremony in Harare, on 28 December, 2017. Photo: Wilfred Kajese / AFP

The military increasingly became involved in politics after 2000 when socio-economic and political developments dramatically changed, following the rejection of the new constitution in a referendum. This was further compounded by the emergence of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which ZANU-PF – as a politico-military institution – viewed as an appendage of the West that would perpetuate neo-colonialism if elected to power.

This led to the appointment of many former retired security services personnel to strategic positions within the ZANU-PF national office. In the same vein, the Joint Operations Command (JOC), a supreme organ for the coordination of state security in Zimbabwe, for the first time in 2002 publicly pronounced on political developments in the country. This culminated in the January 2002 televised statement by the command element of the security forces, led by the ZDF commander, General Vitalis Zvinavashe, who declared that they would only back leaders who fought in the country’s wars of liberation and that any change designed to reverse the gains of the liberation struggle would not be supported.

Analyst Gorden Moyo argues that the military’s growing involvement in the economy through the fast-track land reform programme in the 2000s, the diamond mining in Chiadzwa, and the indigenisation programme, in addition to holding prominent positions in both the party and government, made it difficult for it to adhere to its constitutional mandate, as it became preoccupied with preserving the ruling elite’s access to wealth.

Thus, a number of scholars have argued that the military’s increasing involvement in government suggests an intolerance for elected opposition or dissent. This according to them, has stifled good governance and undermined the will of the electorate.

Furthermore, the military’s continued involvement has worsened the governance crisis, resulting in the West imposing punitive sanctions, especially against the command element of the security, making the country a high-risk jurisdiction. The resultant toxic governance has perpetuated the ongoing financial crisis, high unemployment and healthcare challenges. It has diverted the governing elite from solving the country’s current economic challenges to a vicious cycle of political brinkmanship and continued underdevelopment of the country.

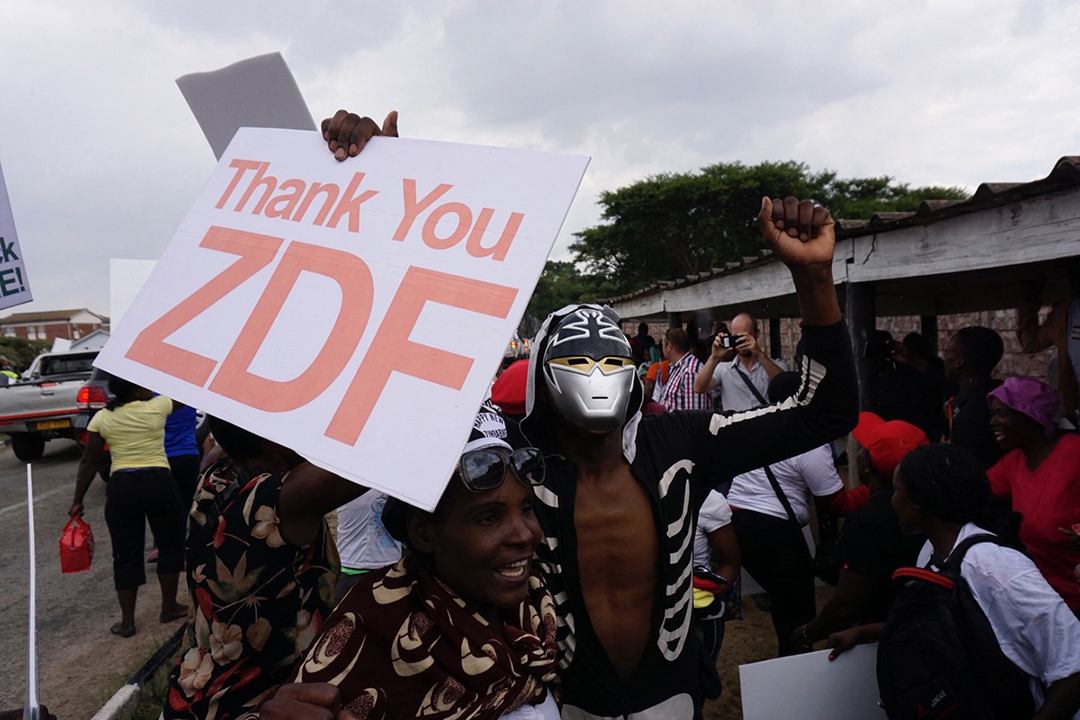

People gather outside Harare’s airport to welcome former Zimbabwean vice-president Emmerson Mnangagwa on 22 November, 2017. Photo: Zinyange Auntony/AFP

Meanwhile, the military played an important role in ending Mugabe’s rule, following the purging of the party leadership. The events of November 2017 were in fulfilment of the warning in 2016 by the then commander of the ZDF, General Constantino Chiwenga that “we [the military] are stockholders of the country. Some are stakeholders. Stakeholders come and go, but stockholders have nowhere to go, so we are stockholders, we came with it [Zimbabwe]”. This statement means that those who fought the liberation struggle have vested interests in the future of Zimbabwe and as such should intervene in defence of the constitution and the flag.

Tendi argues that Mugabe’s refusal to meet with the command element of the military on 13 November, 2017 to deal with increasing disagreements within ZANU-PF triggered his demise. Thus, the military’s intervention through Operation Restore Legacy (ORL) was ostensibly designed to protect national interests and, as per the ZDF’s statement on 15 November, 2017, to “pacify a degenerating political, social and economic situation in our country which, if not addressed, may result in violent conflict”.

It is important to note that the ZDF’s actions were not a coup and President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s eventual takeover of the state passed the constitutionalism barometer.

After ORL, the military, due to their competencies and ideological orientation, increasingly became involved in state affairs. Ndawana (2020) views these appointments as an acknowledgement that “the new administration’s power was derived from, and resided in, the military…and has had a negative impact on a number of democratic institutions, including but not limited to the judiciary, security services, civic organisations and the electoral management body in the country”.

This article has provided the political and socio-economic historical antecedents to the debate as to whether Zimbabwe is a militarised state operating on the whims of the military. From the findings, there are indications that a number of problems that form part of the crisis are throwbacks to unresolved colonial legacy challenges.

Zimbabwe, like any state, uses its human resources and deploys them to positions it deems will derive the maximum benefit. This is not peculiar to Zimbabwe. For example, the current and past three administrations in the United States (US) have appointed former military personnel to head strategic departments.

The findings also do not support allegations that the ZDF is in violation of the constitution, and its involvement should be seen in the context of the military’s historical genesis as a politico-military organisation.

Great enlightening piece