A nuclear future for Africa will end up a game of Russian roulette

Russia is becoming increasingly aggressive in attempts to exert its influence in Africa, and nuclear energy is an area in which they are making major inroads. With Africa’s energy deficit and Russia’s comparative advantage in this field, advocates suggest this is an approach which could deliver win-win solutions for both parties. However, this is not a view that is universally held. The debate therefore continues to rage around whether the nuclear approach is simply pragmatic, or whether it is dangerous, unsuitable and a potentially damaging option.

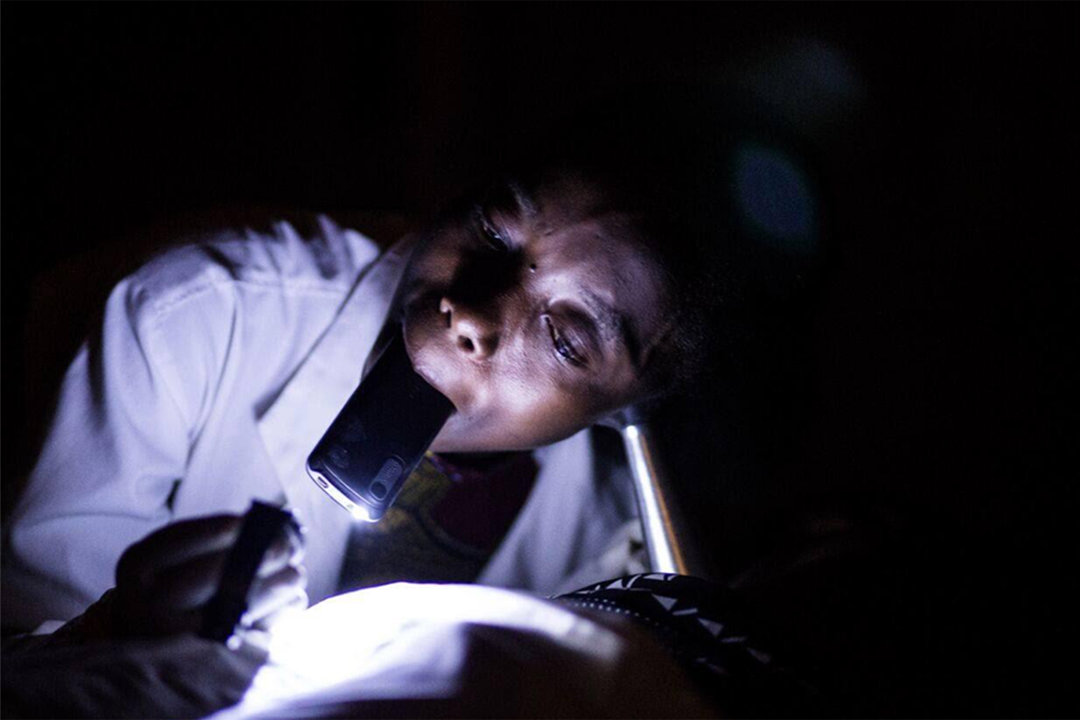

Answering this question effectively requires a nuanced understanding of a number of intricately linked complex factors, namely, the continent’s energy needs; the pros and cons of nuclear energy; how Russian energy diplomacy works in practice, and the strategic rationale for Africa to pursue this avenue. By assessing the current state of affairs alongside past progress and future prospects, a clearer understanding of the potential and pitfalls of this approach is possible. First, it is important to understand the continent’s energy deficit. Despite being home to some 20% of the world’s population, Africa currently accounts for just 4% of global power supply investment. Only 40% of Africans have access to electricity, leaving 600 million people in the dark.

According to the International Energy Agency’s Africa Energy Outlook 2019, the global population without access to energy will become increasingly concentrated, with 90% without access to electricity and almost 50% without access to clean cooking in 2040 living on the African continent.

The status quo is clearly untenable, especially in light of the continent’s evolving demographics. Simply put, today’s policy and investment plans are still not enough to meet the energy needs of Africa’s growing population.

With over 1,000 GW of additional power urgently required to address this power gap, the need for cheaper, more sustainable energy alternatives has become urgent. In this context, the search for new sources, partners and strategies is accelerating. Recently, a number of African nations decided to pursue nuclear power industries or are currently considering this option. Africa is largely virgin territory for this mode of energy. Indeed, at present there is only one operational nuclear power plant in South Africa, representing the full extent of the continent’s functional nuclear capacity. However, this is changing fast.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi make a press statement following the 2019 Russia-Africa Summit at the Sirius Park of Science and Art in Sochi, Russia, on October 24, 2019. (Photo by Sergei CHIRIKOV / POOL / AFP)

However, nuclear’s association with weapons triggers grave concerns about safety. Indeed, for critics, potential for a nuclear meltdown like Chernobyl and Fukushima outweighs the positives of nuclear power, as do the high initial costs and environmental impacts of the nuclear waste produced. African states are expressing a desire to pursue this route, and Russia is expressing eagerness to make it happen, Moscow’s influence on African countries is starting to grow. To be sure, Russia is a major player in the nuclear market. It accounts for 7% of world uranium production, 20% conversion and 45% enrichment of this element, as well as for the construction of 25% of nuclear power plants in the world.

Russia’s energy diplomacy, which centres on two imperatives – profit and power, is the primary avenue used to achieve this. The Russian government, and more specifically Rosatom, has been used to woo African nations into making deals. For Russia, Africa is too big to ignore and an important partner in a changing global geopolitical landscape in which it is looking to assert itself as a dominant power. This theme was strongly emphasised during the 2019 Russia Africa summit in Sochi, which was billed as the start of a new era of Russo-Africa relations.

Understanding Russia’s broader strategic aspiration in Africa requires understanding the broader geopolitical context. Historically, Russia and many African countries’ leaders share close ties and existing relationships to lever as a result of the assistance Russia offered during the time of African independence and the Cold War. African states are of strategic interest to Russia in terms of the geopolitical support they can offer – African states comprise the biggest geographic voting bloc across a multitude of global diplomatic, security and economic institutions and organisations.

There is a broader economic imperative behind this rapprochement, too. As Aailya Vayez notes in her August/September 2020 paper on the evolving nature of Russia-Africa relations for The Republic, “the looming prospects of shrinking national natural resource reserves have extended into the country’s nuclear sector, with uranium reserves in shortage. Uranium extracted from African countries, such as Egypt, South Africa and Namibia, has become a significant raw material for Russian nuclear companies. This has gradually pushed Russia to become an importer of many raw minerals.”

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi make a press statement following the 2019 Russia-Africa Summit at the Sirius Park of Science and Art in Sochi, Russia, on October 24, 2019. (Photo by Sergei CHIRIKOV / POOL / AFP)

Meanwhile, African countries see Russia as a partner that is not morally, politically or otherwise prescriptive. Russia’s trade and investment in Africa without conditions or imposition of ideals means that African countries view Russia and the related relations in a positive light – opening the way for further economic interactions.

For African countries that lack financing to enhance energy infrastructure, the value proposition around nuclear is clear. Rosatom provides cheaper products than its competitors, is ready to loan money for construction and take care of the disposal of nuclear waste, and, in the conditions of constant blackouts, the continent needs uninterrupted, environmentally friendly and inexpensive electricity supplies as never before.

However, Russian engagement is not without risks. What African economies stand to gain in terms of huge investments into cheap and reliable electricity, increased access to global markets and economic opportunity, may undermine governance and lead to a potential loss of institutional oversight.

The recent headline grabbing nuclear deal proposed between Russia and South Africa is a clear example of the secrecy and lack of transparency associated with such transactions. It was only after strong pushback from South African civil society, independent media and robust institutions that the deal (which made very little commercial sense) was aborted.

However, other countries with less sophisticated systems and weaker institutions may be less lucky and fall victim to such malfeasance. Building nuclear plants with Russia would also open up those African nations to the vagaries of energy diplomacy relations with the country, which if evidence with Europe is anything to go by, could carry disastrous consequences. Indeed, if things turn sour, political displeasure could be expressed in unconventional ways – as was evidenced when Russia shut off gas supplies to Europe during the winter of 2015. Load shedding via Russia may become a reality for African countries who fail to manage their arrangements pragmatically and who enter into lopsided, unfavourable deals. For average citizens, the opacity around these government-to-government contracts should be carefully monitored.

Then there is the issue of debt. To contextualise, over the past 20 years, Moscow has written off $140bn to foreign borrowers, of which $20bn came from African states. The persistent pushing of expensive nuclear projects in countries with a bad credit history suggests that there may be a political motivation overriding economic calculations. African countries need to be careful of ending up on the wrong side of exploitative practices, which are not mutually beneficial and could saddle them with unanticipated budgetary consequences. A more streetwise approach is therefore needed.

Finally, there are concerns around the capacity of African states to manage these entities and questions on whether nuclear is actually fit for purpose. Insufficient infrastructure and a lack of human resources are key constraints which would hobble the success of such endeavours. Deep technical skills and experience is required to run such reactors, and unfortunately these are not in high supply on the continent.

In theory, if managed sensibly, nuclear energy could be a game changer for the continent. Indeed, the peaceful use of nuclear energy could act as an instrument to achieve national, African (Agenda 2063) and international development goals such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

However, there are a number of important caveats to this. Given the dangers associated with this mode of energy, sound governance and management will be needed to prevent sub-optimal societal and economic outcomes. Here, co-ordination and sequencing will matter, as will the need to “strengthen relevant bodies responsible for nuclear governance on the continent, improvement of national-level legislation on nuclear safety and security, and promotion of public debate on these issues”, as noted by the South African Institute of International Affairs’ (SAIIA) Atoms for Development project.

In the absence of these measures, gambling on a future in nuclear will end up being the equivalent of a game of Russian roulette – both literally and metaphorically. The rewards may simply not be worth the risk.