The COVID-19 pandemic has presented a stark reminder that advances in access to education in recent decades should not be taken for granted. Children have suffered severely from global lockdowns that have prevented access to schooling and, in many cases, severely compromised their nutrition.

Thelma Mapika, a grade 7 school student, stands at her family’s doorway in Mbare, Harare, on March 30, 2020, during the first day of a scheduled 21-day lockdown declared by the Zimbabwe government to try and curb the further spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus. Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa declared a 21-day lockdown from March 30, 2020, curtailing movement within the country, shutting most shops and suspending flights in and out of Zimbabwe. Jekesai NJIKIZANA / AFP

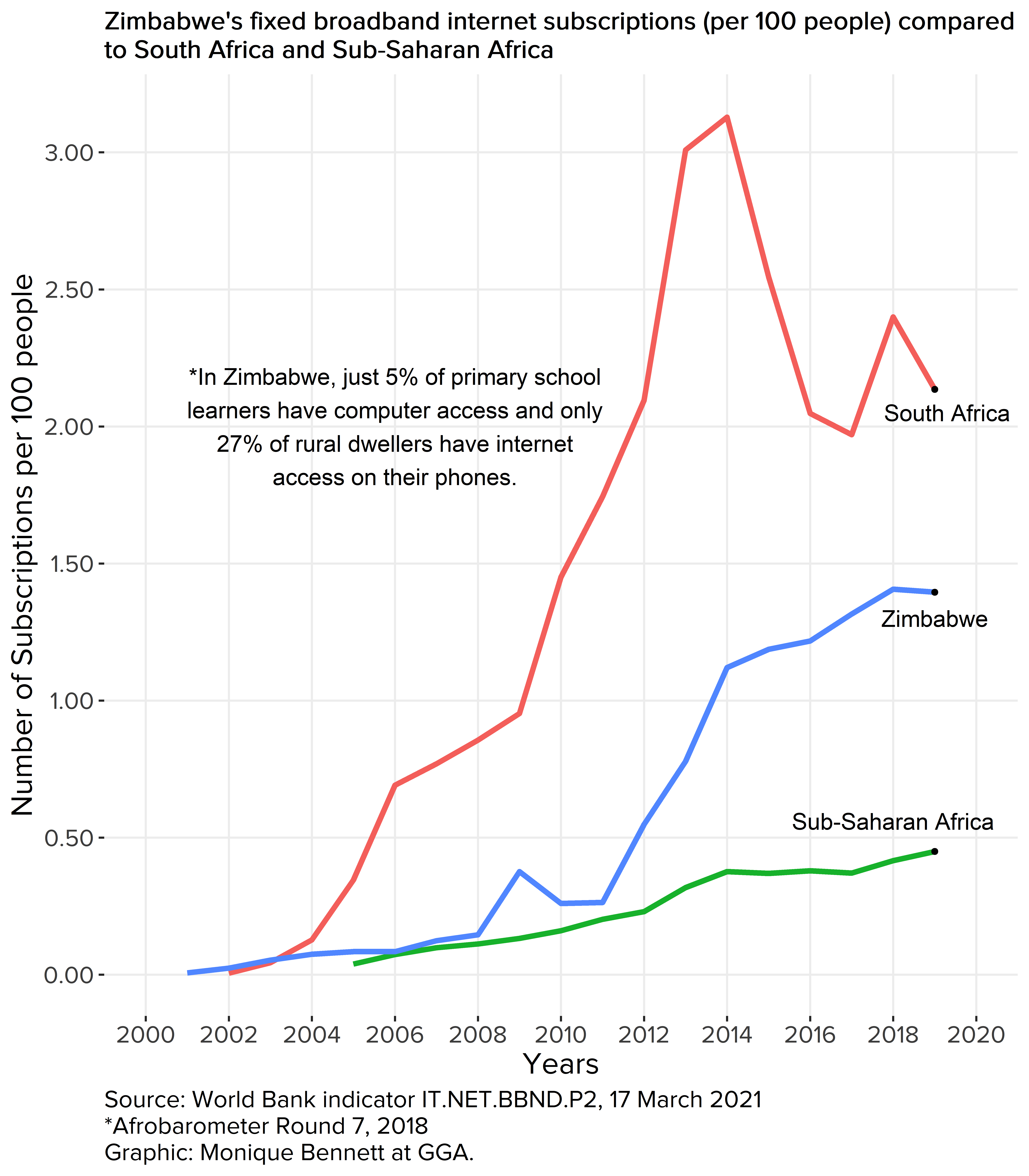

In Zimbabwe, we have seen how COVID-19 has had a disproportionately negative impact upon the rural learners, who constitute at least 70% of the country’s school enrolment. The rural learners often do not have the same level of access to the internet and kinds of education technologies and learning tools available to their more well-connected urban peers.

The 2020 Grade 7 results confirm this. As important as COVID-19 safety measures are, the Zimbabwean government’s 2021 ‘back to school’ plan and conversations about the COVID-19 response must go beyond the ‘handwashing, sanitizing and social distancing’ emphasis, by recognising and addressing the major deficiencies and inequalities within Zimbabwe’s education sector which the pandemic has laid bare.

This is a sector which, in the 90s, had a formidable reputation, with one of the best literacy rates in Africa despite pre and post war governance challenges. There is an opportunity for the Zimbabwean government to utilise new technologies to fundamentally change how rural education is provided, while also addressing the longstanding issues of teacher remuneration and other key challenges within the sector.

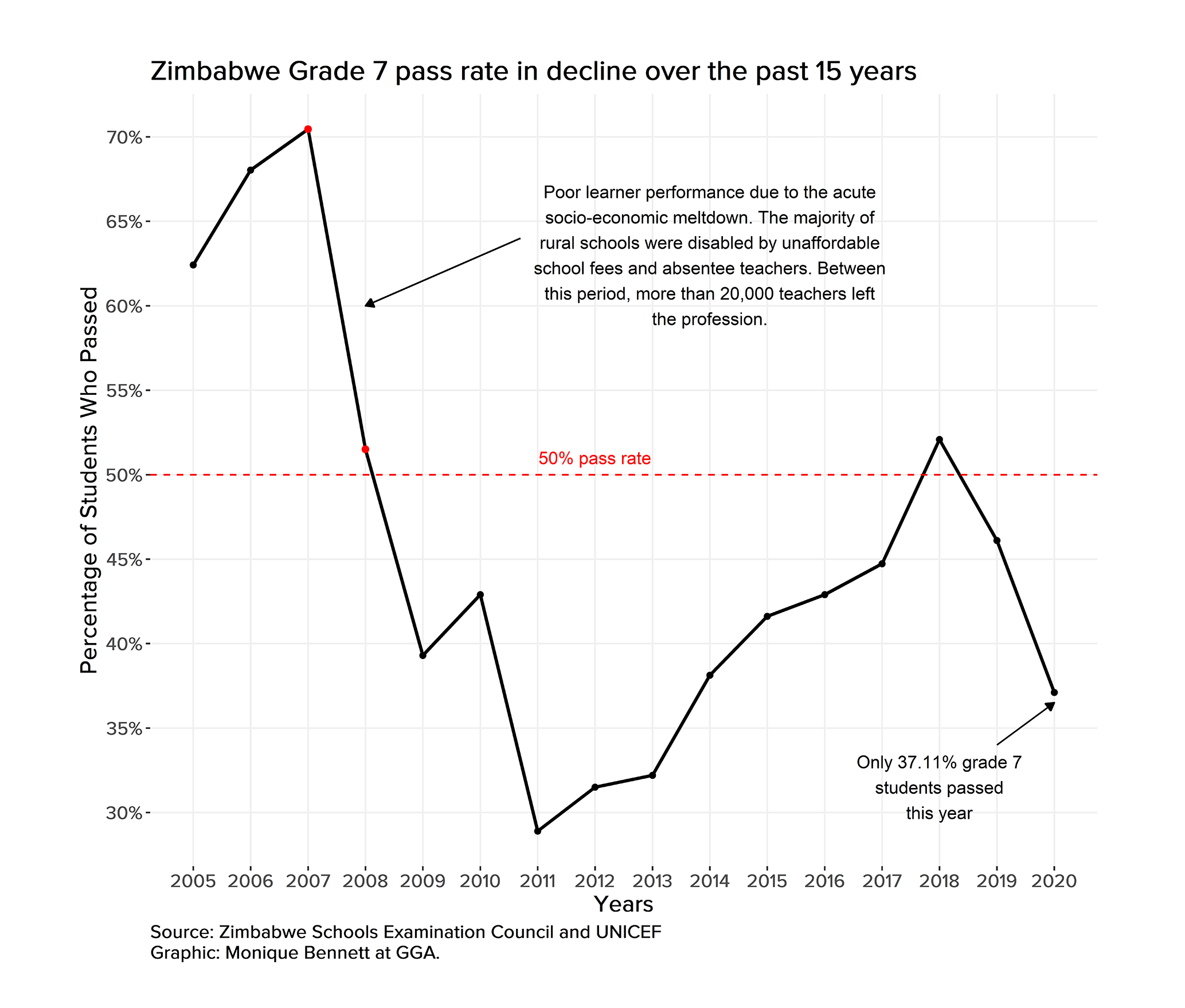

Lessons from the dismal Grade 7 results.

The 2020 Grade 7 Examinations results, recently released by the Zimbabwe School Examinations Council (ZIMSEC), reflected a dismal pass rate of 37.11% from an equally low 46.9% in the previous year. Of the 327 559 candidates who sat for the examinations, the highest number of those who passed were in urban based, largely private schools in the metro provinces of Bulawayo and Harare. In some of Zimbabwe’s rural provinces, several schools recorded zero percent pass rate. Further analysis of the results revealed that in Lupane and other parts of the country, some Grade 7 candidates are illiterate.

Although the COVID-19 lockdowns’ almost year-long school closures posed major disruptions to learning, these results reflect a decades-long downward trend which bucks against the global trend of a massive increase, on average, of access to schooling across the developing world over the last few decades. Zimbabwe’s downward trend is rooted in systematic neglect, especially of rural learners, that foreshadows the failure of the country’s public education system.

Four decades after the attainment of independence, the fact that learners are emerging illiterate, after at least seven years of primary school education anywhere in Zimbabwe, is scandalous. As noted by the Borgen Project, ‘The ability to read and write is one of the few skills with the power to completely change a person’s life. Literacy is vital to education and employment, as well as being incredibly beneficial in everyday life.’ The cases of illiteracy not only reflect the cost of bad governance but simmering inequalities that have been ignored. A significant section of the population has been and continues to be left behind. The country’s leadership needs to urgently exercise political astuteness and action sustainable solutions that set Zimbabwe’s education on a path towards the full realisation of Sustainable Development Goal 4, which seeks to ‘ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning.’

Refocusing the debate

Refocusing the debate

Some of the interpretations of the dismal Grade 7 results spoke volumes about the incapacity of the country’s leadership (or lack thereof) in advancing solutionist thinking. There is need to refocus the debate from the deep political polarization in the country. Cain Mathema, the Minister of primary and secondary education, foreclosed constructive solution-driven conversations, dismissing the results as a reflection of the negative impact of western imposed sanctions. Further to this, the ZIMSEC board chairperson, Professor Eddy Mwenje, reductively attributed this clearly decades long downward trend to COVID-19 induced setbacks. As COVID-19 has become a characteristic alibi in the face of its incompetence, the government continues to bury its head in the sand, overlooking the need for further investigations into why, for example, some candidates did not turn up for examinations, even in certain urban areas. Some rural students failed to make it for their examinations due to poor community infrastructure in the face of disasters such as floods.

Decades of lack of political will have led to budget mis-prioritisations that have brought the public education sector in its entirety to its knees. This was greatly to the detriment of learners from socio-economically vulnerable households, which are essentially the majority.

Recommendations

Firstly, Zimbabwe has tangible lessons to draw from the Senator David Coltart-led Ministry of Education’s transformative milestones of the inclusive government era. This era reveals much about the crucial role of political leadership in delivering equality of access and education for all. Despite a dire economic context during that period, the sector recorded notable improvements, including enhanced teacher welfare and a drastic improvement in the textbook to learner ratio, from 1: 15 to 1 : 1 for a minimum of six subjects.

Further to this, Zimbabwe’s ministries of education should deliberately draw lessons from world-acclaimed public education programmes like Singapore’s, which is credited for achieving ‘excellence without wide differences between children from wealthy and disadvantaged families’. This is key to bridging the widening rural-urban learner inequalities within the country. The current Ministry of Education can engage the Government of Singapore on the possibility of bilateral skills and knowledge transfer through capacity building for the country’s education sector.

Photo: Hopewell Chin’ono

The government should also review ongoing and previously implemented projects that are a potential launchpad for rural education technological advancement, such as the Presidential Schools Computerisation Programme, launched in the year 2000, the Rural Electrification Programme(REP), launched in 2002, as well as the Presidential Computerisation and E-Learning Programmes.

Lastly, there are opportunities and lessons from the Strive Masiyiwa inspired and led USD $100 million funded Re-Imagine Rural Zimbabwe/Africa programme that promotes entrepreneurs with solutions to improve rural Zimbabwe/Africa, that could possibly be implemented today.

Conclusion

The Grade 7 results therefore reflect a microcosm of the structural challenges and deepening inequality in the access to this all important public good. Rural learners are lagging behind. Guided by the United Nations, one of the important next steps is for the government to take the lead in advancing funding while at the same time embarking on other creative approaches (e.g. Private Public Partnerships and well managed Community Share Ownership Trusts) to adequately fund this technologically driven future of rural education. Further to this, the government should scale up some of its notable successes, and learn from global best practices to address discriminatory policies and social practices, to ensure that no one remains behind. It is time the government considers rural technological advancement and, more specifically, internet connectivity as a foundational right, a precursor to enabling SDG4.

COVID-19 has only laid bare the unique pre-existent challenges that the country’s socio-economically marginalised rural communities face. The solution must begin with a move away from the partisan, ill-focused rhetoric by policy makers, to constructive engagements aimed at addressing the discrimination and inequality faced by the rural learner and teacher. Securing and directing adequate funding to the education sector to largely address the remuneration and working conditions of teachers is critical. However, the most urgent call in addressing the inequality gap for the rural learner is addressing the infrastructural, technology and connectivity gap, to enable rural learners some kind of soft landing onto this technology driven education era.

COVID-19 has only laid bare the unique pre-existent challenges that the country’s socio-economically marginalised rural communities face. The solution must begin with a move away from the partisan, ill-focused rhetoric by policy makers, to constructive engagements aimed at addressing the discrimination and inequality faced by the rural learner and teacher. Securing and directing adequate funding to the education sector to largely address the remuneration and working conditions of teachers is critical. However, the most urgent call in addressing the inequality gap for the rural learner is addressing the infrastructural, technology and connectivity gap, to enable rural learners some kind of soft landing onto this technology driven education era.

The government, particularly the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, must re-focus the debate and re-orientate funding priorities. As already noted, related projects have been embarked on before. There can no longer be full enabling or realisation of the right to education that does not take into account enabling internet connectivity.