‘The right to life’ is fundamental; an imprescriptible right inherent to all human beings. The Equity and Human Rights Commission states that governments should take appropriate measures to safeguard life by “taking steps to protect you if your life is at risk.” With public healthcare in Africa suffering chronic shortages of critical drugs, medical brain-drain, insufficient public healthcare funding, as well as inadequate pharmaceutical production, are African governments taking appropriate measures to safeguard citizens’ lives?

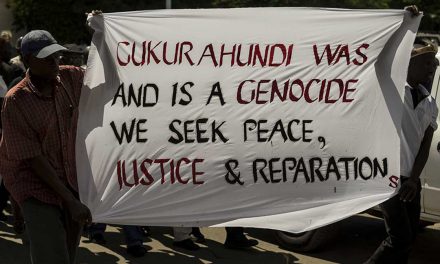

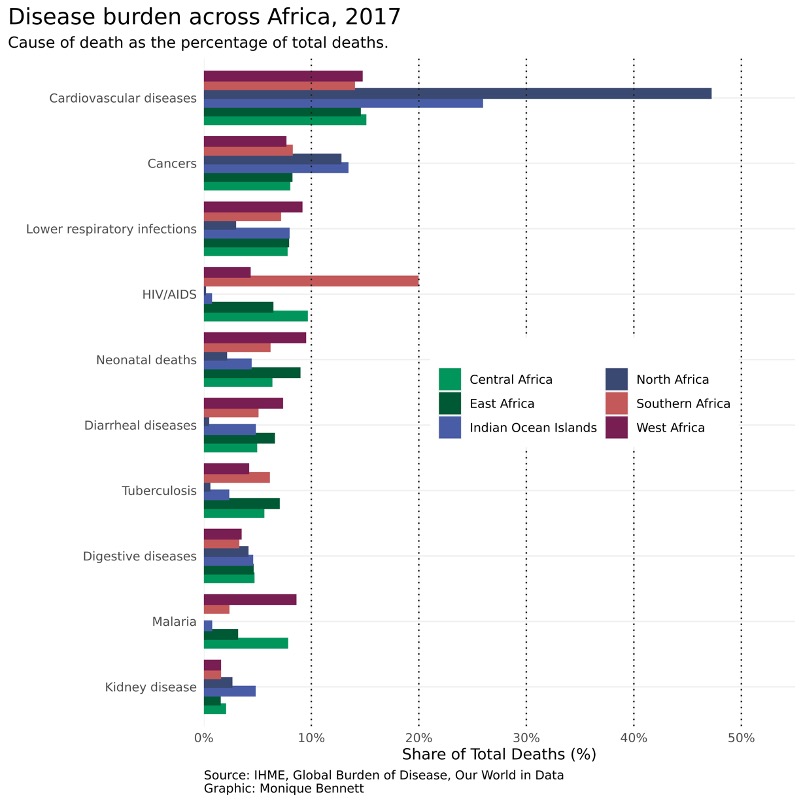

Approximately 80% of Africans in the middle-income bracket, and below, rely on public health facilities. Leading killers on the continent, often described as ‘the big three’ include malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Important to note (as per the figure below) is the transition over recent years to lifestyle diseases like obesity and diabetes. Approximately 50% of under-five deaths in Africa are caused by pneumonia, diarrhoea, measles, HIV, tuberculosis and malaria.

Source: Monique Bennett ©, Good Governance Africa

Source: Monique Bennett ©, Good Governance Africa

According to the International Finance Corporation, health care in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) exhibits the worst performance in the world, with few countries able to spend the $34 to $40 a year per person that the World Health Organization (WHO) considers the minimum for basic health care. Africa’s capacity for pharmaceutical research and development, as well as local drug production, still has a long way to go. Fewer than 40 out of 54 African states have some level of pharmaceutical production.

Most African countries rely on imported pharmaceutical ingredients. The implication may be that citizens will not have access to affordable locally manufactured medicines as prohibitively expensive imports dominate the markets. Another implication is that the shortages of medicines in some public healthcare facilities like local clinics mean that they will often refer sick patients to larger hospitals for basic medicine. This creates a bottleneck at these larger facilities and diverts resources away from their core focus, the very opposite of what should be happening in system-governance terms.

Beyond the medicine shortages and bottleneck problems, several other factors inhibit access to health care, one of which is access to skilled personnel. A brain-drain of homegrown doctors migrating abroad amplifies the pre-existing challenges. Another factor is the sheer under-allocation of resources towards healthcare. Current health expenditure as a percentage of GDP for SSA sits at 5.2% compared with a global average of 9.9%. Compounding the situation, corruption often diverts the little that is allocated away from where it is needed most.

The WHO defines having access to health as having medicines continuously available and affordable at facilities that are within one hour’s walk of the population. To this effect, mobile healthcare services have seen success in some parts of Africa, particularly in remote rural areas.

More research and deliberation are needed on how the major differences between Africa, America, Europe and Asia might matter. Thus far there has been no technical guidance on how African governments should approach their considerably different contexts. The advice is often the same globally while the context is not. African governments should focus on designing tailor-made public healthcare strategies in confronting C-19, for example, subject to each country’s unique demographic and socio-economic characteristics: “[F]ailure to recognise that one size does not fit all could have lethal consequences in this region, maybe even more lethal than those of the virus itself.”

Sustainable Development Goal 3 calls for the promotion of healthy living and the well-being of all. Countries have committed to ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all as well as achieving a range of health targets by 2030. What role should African governments and partners play to support the continent in achieving set targets?

First, a re-allocation of expenditure towards investing in healthcare personnel could contribute to the reduction of brain-drain of homegrown doctors. On average, according to the WHO, 39% of African health budgets are spent on medical products, while expenditure on the health workforce (14%) and infrastructure (7%) is low. An analysis of spending patterns suggests that countries with well-performing health systems invest up to 40% on the health workforce and 33% on infrastructure.

Second, performance (efficiency) has to be improved. In the same WHO report mentioned above, performance is described as an integrated measure of a country’s ability to improve access to services, quality of care, community demand for services and resilience to outbreaks. In SSA, performance is poor across all these dimensions, but particularly in the areas of ensuring access to services and resilience to outbreaks. Precarious health systems are not able to withstand shocks such as disease outbreaks, evidenced by the C-19 pandemic. This is a function of a combination of funding shortages, sub-optimal resource allocation and corruption. The people, institutions and resources needed to deliver health related services are only performing at 49% of their potential capacity.

Third, the pandemic has exposed gaps in health services that require urgent attention in many African countries. A lack of access to testing (along with results backlogs) are hampering efforts to save lives. While many African countries responded swiftly by enacting measures to slow the spread of the pandemic, many also lack the capacity to test for C-19, isolate people with confirmed or suspected cases, trace contacts, and treat those with severe illness. The economic impacts, too, of swift responses were arguably not sufficiently considered.

What matters most for effective C-19 treatment is ICU/oxygenation availability. The global data strongly suggests that economic interventions (lockdowns and/or bans on alcohol, etc.) make little difference – on a log scale, the infection rate is almost exactly the same shape over time in every context. This suggests that optimal responses are those that effectively communicate the message of social distancing and invest in oxygen capacity for those most badly afflicted, but do not shut down economies.

While African governments urgently address the demands of the Covid-19 pandemic, they should simultaneously address co-morbidities (particularly diseases presenting with a cough or fever, along with diabetes). Given the known influence of clinical activity and health seeking behaviour on TB and HIV detection, primary healthcare staff need to be alert for these conditions during the C-19 pandemic. Undetected TB and HIV will exacerbate the C-19 death count.

Finally, an extensive opportunity cost associated with governance responses to pandemics is “C-19-diversion” (resources allocated to C-19 at the expense of other important burdens that suddenly appear less urgent because of the novelty of pandemics). Diabetes and cancer treatments are among the casualties of this diversion. Diabetes is the co-morbidity most strongly associated with C-19 deaths. African governments should, therefore, urgently invest in eliminating it, for instance through removing taxes on nutritious foods and imposing high taxes on refined carbohydrates. More efficient C-19 testing, combined with efforts to reduce co-morbidities, will likely lead to better future healthcare outcomes.

During and beyond the C-19 pandemic, African governments should re-think their public healthcare systems and tailor-make them to serve their unique contexts, bringing the healthcare element of the right to life front and centre in their policies and programmes to improve citizens’ lives.

This article originally appeared in Business Day