A protest against the plan by Dutch oil company Shell to conduct underwater seismic surveys along South Africa’s East coast, at Muizenberg Beach, in Cape Town, on December 05, 2021. Photo: Rodger Bosch/AFP

In our previous article, we analysed the initial Shell court judgment in relation to the recent 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) agreements that South Africa made in pursuit of the global transition towards a zero-carbon emissions future. The court’s 2021 decision to reverse the initial judgment and interdict Shell from continuing with its seismic oil exploration survey highlights the growing significance of integrating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) performance into business decision-making processes.

ESG performance speaks to three factors that have historically been overlooked in measuring firms’ impacts. Typically, a firm’s impact on the environment and the communities in which it operates has not been captured in its financial reports. Similarly, governance principles such as thorough board-level oversight to ensure operational integrity have been neglected. A growing global movement is allocating considerable effort towards ensuring that ESG performance becomes a key criterion through which firms in all industries attain access to responsible finance.

While ESG factors have affected a range of industries, the extractives industry has deep and unique ESG risks that are proving challenging to address. However, the ruling to stop Shell from continuing with its seismic exploration survey off the Wild Coast has shown that ESG matters significantly, as it will increasingly form part of the external legal constraints to which firms are subject. For this reason, and because ESG makes inherent business sense, it should be taken seriously in firms’ decision-making processes.

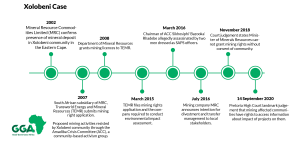

The Shell court judgment forms part of a series of significant South African and international decisions, such as the Xolobeni and Okpabi cases respectively. In the Xolobeni case, an Australian mining company showed interest to mine for titanium ores and other heavy minerals in the Xolebeni area in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. The community of Xolobeni have resisted the proposed mining activities for almost 15 years and the North-Gauteng High Court ruled in September 2020 that the communities have a right to see application licences and must be thoroughly consulted in the process.

This judgment illustrated that the interests of both mining companies and communities must be properly weighted. More importantly, it illustrated the need to involve all interested and affected parties in the consultation process, which needs to be conducted in a transparent and just manner. It should be non-negotiable that information about mining projects that affect communities need to be accessible and shared for public interest and knowledge.

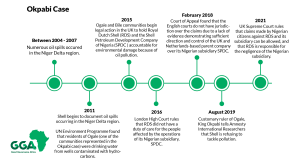

In the Okpabi case, over 40 000 Nigerian citizens of two affected areas in the Niger Delta brought a lawsuit against Royal Dutch Shell Plc (RDS) and one of its Nigerian subsidiaries (Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria) for oil spills and pollution from pipelines operated by the subsidiary between 2004 – 2007. This case was brought to the UK Supreme Court to hold the parent company, RDS, directly responsible and accountable for the actions of its subsidiary in the Niger Delta. The impact of the oil spills and water pollution caused substantial environmental damage that resulted in unsafe water for drinking, fishing, agriculture, and recreation.

To this end, the UK Supreme Court ruled that RDS, as the parent company, owed duty of care to the Nigerian citizens in relation to environmental damage and human rights abuses by the Nigerian subsidiary. Due to the significance of the environmental damage, RDS was ordered to pay an undisclosed amount to the farmers who claimed that the oil spills ruined livelihoods in the village. This highlights the real risk of financial loss because of inadequate policy implementation, procedures, and due diligence that ought to be performed in the company’s international operations. Therefore, firms require more active corporate governance and internal due diligence that is effectively controlled and reported. Through taking ESG performance seriously, these significant risks can be managed and mitigated.

ESG matters. The above-mentioned cases show the prominence that ESG factors are beginning to gain in the regulatory and risk space. The growing convergence between ESG criteria and legal frameworks shows that there is a substantive business case for ESG integration. Robert Armstrong of the Financial Times, a long standing ESG sceptic, warned that ESG would merely become a new kind of corporate greenwashing in which firms were rewarded for intention rather than action, and even become subverted as a way to avoid regulation. For ESG to effectively align with legislation, then, clear regulations regarding disclosures on ESG related risks must be built. These should ensure transparency and good corporate governance and set the rules of the game clearly for all players.

To paraphrase Tariq Fancy’s criticism of ESG performance and ESG investing, ESG without legislation creating clear boundaries for what can be accepted as ESG performance is a dangerous distraction from the real issues and a major risk to the present economic system. The current economic and global accounting system has inadvertently permitted firms to offload negative externalities – the divergence between private returns and social costs – onto communities and ecosystems that can least afford it. It has also, in the process, caused significant levels of inequality and driven climate change. ESG requirements – correctly legislated – afford the opportunity to internalise these costs and manage the risks, an essential target if we are to maintain system stability.

The outcome of the Shell case, and criticisms from environmental activists, expose some of the tensions between oil and minerals exploration companies on the one hand, and environmental groups, communities, and policy makers on the other. Arguments that the prevention of mineral exploration results in a major economic cost dovetail with comments from South African Minister of Minerals and Energy, Gwede Mantashe, who suggested that the protests by environmental groups is akin to apartheid and colonialism. Similarly, Nigerian Vice President Yemi Osinbajo has argued that fossil fuel divestment campaigns are delusionary. Nnimmo Bassey and Anabela Lemos have responded, however, with a significant and compelling critique of Osinbajo’s arguments.

In 2021, both the International Energy Alliance and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produced reports warning that all new fossil fuel exploration should stop with immediate effect to keep the planet within the 1.5-degree warming boundary agreed in the Paris Climate Agreement. Renewable sources of energy are increasingly feasible and scalable.

In developing countries like South Africa, access to cheap and consistent fuel sources is considered essential for the development of their economies. As is often argued, it can appear unfair for these countries to be forced to halt their development to solve a climate crisis for which they are not responsible. Commercial oil discoveries off the Wild Coast could potentially remove the country’s reliance on fuel imports and boost the struggling economy, if said oil was available at a sufficiently low marginal cost of production. Similarly, the exploration of the mineral sands in Xolobeni could potentially boost both the local and national economy. All of which is much needed in South Africa, a country suffering from severe unemployment and poverty. However, the negative externalities of exploration must be considered – from pollution and damage to ecosystems, to the healthcare consequences for miners and their communities. Moreover, the opportunity costs of such investment decisions must be fully weighted against their alternatives, which may prove both environmentally and socially less costly.

Communities, as stakeholders that will bear both the negative and positive externalities of natural resource extraction, must form part of the decision-making process. If a community such as Xolobeni has agreed that the value of eco-tourism to the region is greater and more sustainable than the mining of the sands and are not in violation of any of the laws of the land, they should be able to stand firm in their convictions, without fear of intimidation, co-optation, and coercion. ESG performance presents an opportunity for such consultation and integration of these communities into decision-making processes as well as reducing the potential costs that might emerge down the line from litigation and fines.

These cases have shown that companies will need to take above-ground risks at least as seriously as below-ground risks and genuinely consider other stakeholders as they attempt to do business. Equally, legislation will need to be increasingly clear in terms of how ESG risks are to be managed and reported.

[activecampaign form=1]