Mini-grids and solar systems are a lifeline for Africa’s underserviced rural health clinics

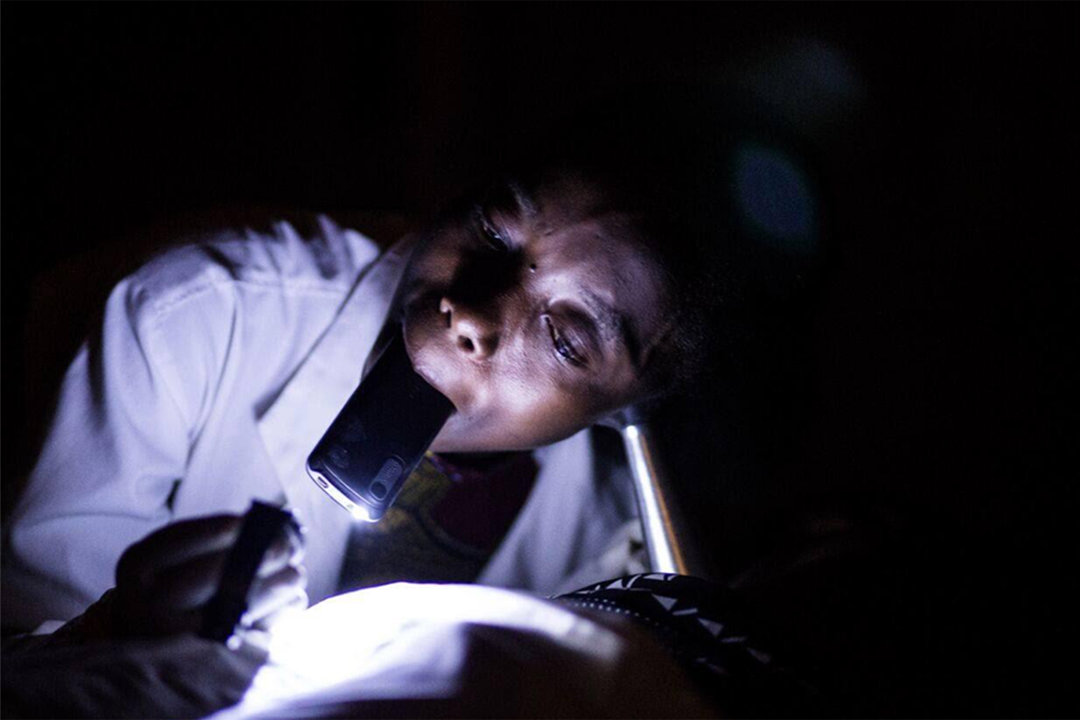

Laura Stachel first realised that lack of electricity impaired the delivery of life-saving care when she conducted research in a state hospital in Nigeria in 2008. As an obstetrician, she watched helplessly as her colleagues struggled to deliver babies in near darkness, administer intravenous medication by candlelight and conduct surgeries by the ambient light of windows or by flashlight. Resuscitating newborns in a hospital where light and electricity were only available 12 hours a day was tough.

With her husband, Hal Aronson, she designed a standalone solar electric system for the hospital and provided a solar-powered blood bank, and as a result, maternal deaths dropped significantly. “We witnessed the impact of solar electricity on medical and surgical care,” she told Africa in Fact. “Soon, surrounding Nigerian health facilities began asking me for solar power, and I knew we needed a solution that could scale.”

Out of that, a solar suitcase, a rugged, compact solar electric system for maternal healthcare facilities in need of an immediate and reliable source of electricity, was born.

Equipped with medical-surgical lights, headlamps, phone charger, a foetal Doppler to assess the foetal heartbeat, and charging ports for other devices, the suitcase became a lifesaver.

Now, under We Care Solar, the suitcase is used in 20 countries, mainly those with high rates of maternal mortality and low access to electricity, initially in Liberia, Uganda, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe, and latterly in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania, Eritrea, Mozambique, Gambia, and Ghana. The suitcase allows health workers in energy-poor regions to assess patients for signs of infection, conduct examinations, make cell phone calls for consultations or patient transfer, adhere to infection control protocols and avoid cross-contamination.

And, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit Africa, the solar suitcase found added meaning. “We added infrared no-touch thermometers to the solar suitcase to assist in the detection and monitoring of patients with infection,” Stachel said. The solar suitcase is useful for primary care providers during COVID-19, she added. Light is essential for examining patients, diagnosing medical conditions, and performing procedures.

It is no surprise that when COVID-19 hit Liberia in April, Bentoe Tehoungue, the director of Family Health at Liberia’s Ministry of Health, sent an SOS asking for electricity and light. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 28% of healthcare facilities benefit from reliable electricity, says Sustainable Energy for All. For Tehoungue, after five months, the only response for help came from UNICEF, providing direct support for the neonatal and paediatric unit at the James David Memorial Hospital, near Monrovia, the capital, which included equipment and solar power.

“Everyone knows that when you are in the dark, you are bound to make mistakes and have cross-infection,” Tehoungue told Africa in Fact. This means there is a risk of spreading infections between patients as well as a risk of infecting yourself, she added.

During the pandemic, hospitals in Monrovia, Grand Bassa and Marpula were treating patients with COVID-19 in facilities that rely on an unstable supply of grid electricity supply, Tehoungue said. “They mostly depend on generators,” she added, pointing out that solar power was more sustainable, whereas generators continuously needed fuel and maintenance.

Long before the pandemic, in 2018, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) had provided solar electricity to five hospitals and health centres, and discussions to scale up the solar electrification of hospitals were ongoing, said Tehoungue.

Long before the pandemic, in 2018, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) had provided solar electricity to five hospitals and health centres, and discussions to scale up the solar electrification of hospitals were ongoing, said Tehoungue.

Unsurprising then that solar systems or mini-grids have become a lifeline to underserved rural health clinics, especially as COVID-19 cases surged across Africa. In the past eight months, at the time of writing in October, health services in several African countries had been connected to solar. For example, 10 clinics in Zimbabwe’s Matabeleland North Province were lit through a donation of solar panels and accessories from local solar company, Zonful Energy, to assist in the fight against COVID-19.

In Tanzania, JUMEME, a local mini-grid operator co-funded by the EU, used its local solar-hybrid mini-grids to provide 10 healthcare facilities in the Lake Victoria Islands, with free electricity services for three months. Meanwhile, in Nigeria, The Rural Electrification Agency installed the largest solar hybrid power plant in Abuja, with a capacity of 53.1kW, providing electricity to the isolation centre at the University of Abuja Hospital and 30kW solar hybrid systems serving two isolation centres with more than 200 beds combined in Ogun State in south-east Nigeria.

A sub-Saharan midwife attends to her patient using the torchlight on her mobile phone. Photo: We Care Solar

“Reliable power supply has ensured that core systems for the management of health programmes function effectively,” Saleban Omar, head of UNDP’s Solar for Health Initiative and its senior regional programme advisor for Africa, told Africa in Fact. Uninterrupted systems for data input and analysis contribute to efficient and accurate quantification and distribution of medicines, patient tracking, and monitoring of overall health system performance, Omar said.

A shopkeeper stores solar panels in a street in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso in September 2019. Photo Issouf Sanogo/AFP

Through solar power, the clinics can now maintain the quality of temperature-sensitive medicines, safely sterilise equipment and store vaccines, while also increasing access to quality health services, including safe delivery for pregnant women.

In Zimbabwe, for instance, where Solar for Health initiative operates, many clinics had only four hours of power supply a day. The programme partnered with the Global Fund in equipping 405 health facilities with solar panels, which meant that “people can get the healthcare they need when they need it”, said Omar.

Reports from Zimbabwe, Omar said, showed a growing number of pregnant women and children under five years old accessing rural health facilities, with some clinics reporting an increase of up to 80%. The Solar for Health initiative has enabled clinics to extend their hours of operation, as well as enable better retention and recruitment of healthcare workers in remote settings, ensuring effective, safe healthcare, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, he said.

Apart from Zimbabwe, the initiative has supported more than 900 health centres and storage facilities in Angola, Chad, Liberia, Libya, Namibia, Nepal, Sudan, South Sudan, Yemen, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, in the past two years.

In May 2020, Power Africa, under the auspices of USAID, launched a Solar Electrification of Healthcare Facilities grant competition to “support accelerated provision of off-grid energy and reliable power solutions to improve the readiness and resilience of healthcare facilities in rural, peri-urban and urban communities of sub-Saharan Africa”. Grants range from $100,000 and $500,000.

Omar said that to keep solar running, they are seeking funding from the Green Climate Fund to design a climate change mitigation programme known as the Solar for Health Programme: enabling the provision of sustainable low-carbon energy services to public health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa.

The proposed programme will design and implement performance-based payment models for solar-powered solutions to provide clean, affordable, and reliable energy services to health facilities. It will also establish a regional knowledge platform on climate change and health.

Omar said they would continue supporting public health institutions through direct procurement and by offering reliable and timely delivery of quality-assured products, while helping governments to build sustainable and resilient health systems and improve national procurement and supply chain systems.

“We also provide technical expertise to strengthen policy and regulatory frameworks, improve procurement strategies and regulations, and address potential barriers to equitable access to affordable medicine,” he said.

However, the UNDP’s Solar for Health initiative is not without its challenges. The programme has had to contend with the unavailability of appropriately skilled manpower, enabling environments, and lack of finance. These were just some of the biggest challenges facing the solar sector in some of the countries the programme operated in, Omar said. The initiative partnered with the Physics Department of the University of Zambia to establish a Solar Energy Centre of Excellence that supports the growth of the solar energy industry through training, testing of equipment, and physical deployment of PV technologies in health facilities.

“We continue to promote sustainable health procurement by working together with manufacturers on social and environmental scorecard assessments, reducing CO2 emissions through enhanced data collection and analysis of shipments, and through medical waste management and packaging optimisation of health products,” said Omar.