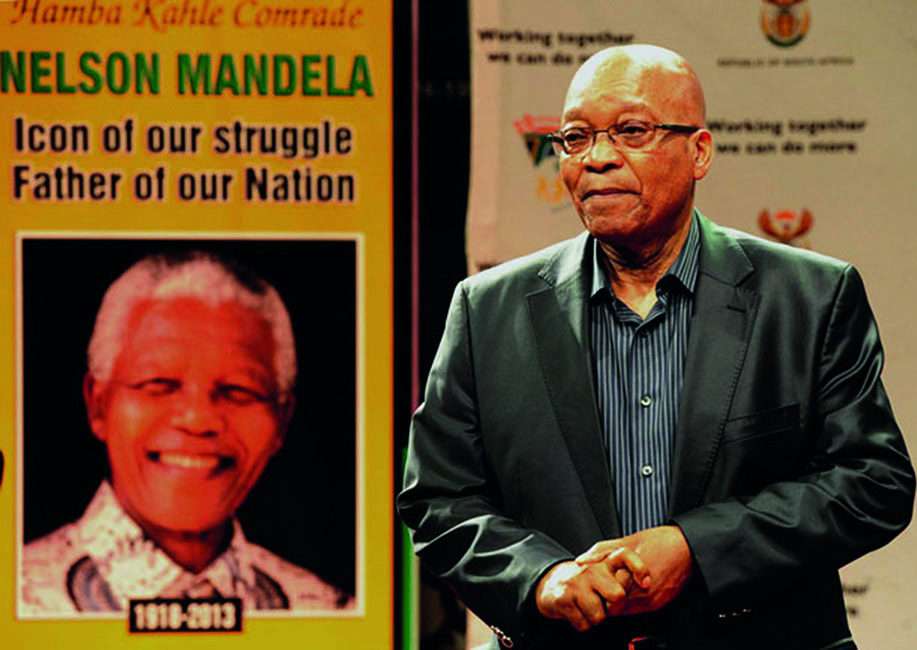

President Jacob Zuma at the Sefako M. Makgatho Presidential Guesthouse in Pretoria. Image: Presidency of South Africa

As the pressure mounts on president Jacob Zuma, the race to take over the South African presidency is anything but clear-cut

Although the ruling African National Congress (ANC) has downplayed reports of a leadership contest, power jostling is already evident at the top levels of the party. The race for a new South African president has begun.

Whether it is because he is deposed, or because his term ends in December when the ANC holds its elective congress, President Jacob Zuma will soon hand over the reins to one of a handful of pretenders to the presidential throne. Four candidates are emerging: Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, former African Union Commission Chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, Human Settlements Minister Lindiwe Sisulu and speaker of the National Assembly, Baleka Mbete.

Ramaphosa, Zuma’s deputy president since 2014, is seen as the strong frontrunner in the race. In April, he kicked off his campaign on a dramatic note when he publicly distanced himself from the Zuma government and called for an inquiry into allegations of “state capture” following revelations of extensive contacts between the president and a group of business people centred around the Guptas, a wealthy immigrant family.

Days later, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) declared its backing of Ramaphosa as the successor to Zuma, who was jeered off stage at the union federation’s May Day rally.

Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa. Illustration: Vusi Malindi

Business and political analysts agree that Ramaphosa’s chances are good, even though the former union leader and prominent businessman is on the periphery of ANC structures. Within the party, leadership ascendancy traditionally plays out from the branches upwards to the National Executive Committee (NEC).

“[Ramaphosa’s] power base within the ANC is uncertain and perhaps limited, so his challenge will be getting a province or two to run a campaign for him to build a base,” says Siphamandla Zondi, professor of political science at the University of Pretoria in South Africa.

Cosatu is Ramaphosa’s strongest lever in this, having undertaken to campaign on his behalf. Ramaphosa’s provincial strongholds are the Eastern Cape and Gauteng, where he has growing support within ANC branches, according to Jakkie Cilliers, chairperson and Head of African Futures & Innovation at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) in Tshwane, South Africa.

“[Ramaphosa] lacks support from the ANC Women’s League and ANC Youth League, but he has the backing of former finance minister and MP Pravin Gordhan and his former deputy, MP Mcebisi Jonas, who are galvanising support for him within ANC structures,” Cilliers told Africa in Fact.

Ramaphosa might secure the presidency by swinging ANC voters in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) too, according to a 2017 RiskMap report by Control Risks, a global risk and strategic consulting firm. “KZN has traditionally been a Dlamini-Zuma stronghold but it increasingly looks like Ramaphosa is going to be able to split the vote through the support of key figures such as Zweli Mkhize (ANC treasurer general) and Senzo Mchunu (former KZN premier),” Control Risks analyst Seamus Duggan told Times Media in February following the release of the report.

Predicted by the late President Nelson Mandela as South Africa’s future president, Ramaphosa, 65, was general secretary of the powerful National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), an affiliate of Cosatu, in the 1980s. A seasoned negotiator and strategist, he is also a qualified lawyer, having completed his LLB at the University of the North in 1981, the year he joined the Council of Unions of South Africa (CUSA) as a legal advisor.

Ramaphosa was elected as ANC secretary general in June 1991, and on 24 May 1994 was elected chairperson of the new Constitutional Assembly. In 1996, after he lost the race to become president to Thabo Mbeki, Ramaphosa moved to the private sector, where he became a director of New Africa Investments Limited, the first broad-based black economic investment vehicle.

Five years later, he founded Shanduka Group, which has stakes in nearly 30 businesses, including Standard Bank Group Ltd., Africa’s biggest bank, and mobile-phone company MTN.

Ramaphosa re-entered politics in 2012, having divested himself of most of his business interests, to become deputy president of the ANC. He was elected deputy president of the Republic in 2014. “He is a leader of great mettle, who would serve South Africa well,” Gordhan said recently.

Meanwhile Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, Zuma’s ex-wife, has wasted no time campaigning across the country after a five-year stint as head of the African Union Commission. Her bid for the presidency is openly supported by key Zuma allies, including the ANC Women’s League (ANCWL) and branches of the ANC Youth League in KwaZulu-Natal and Free State provinces, with a campaign that echoes Zuma’s call for “radical economic transformation”.

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. Illustration: Vusi Malindi

Dlamini-Zuma is known as a good administrator and “fixer” in respect of governance and policy implementation, but analysts doubt she has the political stature to draw support outside of Zuma’s current power base. “She has the potential to generate the numbers needed to win the internal ANC contest, but the ANC needs someone who can also rise above factions and represent a fresh start after almost a decade of Zuma’s presidency,” says Zondi.

The ANC has yet to elect a woman as president but, comments Cilliers, the female ticket is not an advantage in her traditionalist rural support base in KZN. “Also, her populist rhetoric is not advancing her campaign in the urban regions like Gauteng, where the ANC is looking for a more modern style of leadership,” says Cilliers.

Dlamini-Zuma, 68, is a medical doctor, having completed her MBChB at Bristol University in 1978. She was minister of health from 1994 to 1999 under President Nelson Mandea, foreign minister from 1999 to 2009 and minister of home affairs from 2009 until her election to the AU Commission in 2012.

If Dlamini-Zuma takes the presidential seat, there might be potentially dangerous implications for the future of the ANC, which is split between traditionalists and reformists. In a Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) report circulated to RMB clients in April, five political analysts surveyed predicted that Zuma’s continued presence in office, and the possibility that Dlamini-Zuma may succeed him, could place the ANC at risk of losing its majority in the 2019.

The most recent addition in the presidential race, seen as a compromise candidate, is Lindiwe Sisulu, human settlements minister and MP since 1994. Considered to be “political royalty” within the ANC, she has been nominated by the Z.R. Mahabana branch in Keiskammahoek in the Eastern Cape to lead, with the reasoning that she is not “tainted” by political scandal.

Lindiwe Sisulu. © GCIS

Unlike Dlamini-Zuma, Sisulu has done little to garner support at ANC provincial or local branch level. “Her footprint at grassroots level is quite absent,” commented independent political analyst Lukhona Mnguni in a radio interview in April this year – but she has strong resonance with urban voters.

“For these voters, she is a better woman candidate than Dlamini- Zuma, as she is a sophisticated urbanite who, like Ramaphosa, is one of the ‘reformers’ in the party,” says Cilliers. “The ANC ‘high road’ in modern South Africa would be Ramaphosa as president, and Sisulu as his deputy,” he adds.

Sisulu, 63, is the daughter of late ANC stalwarts Walter and Albertina Sisulu, and served as minister of housing from 2004 to 2009, minister of defence from 2009 to 2012 and minister of public service and administration from 2012 to 2014, before taking up her current portfolio. She has a BA (Hons) in history from the University of Swaziland and an MA in history and MPhil from the Centre for Southern African Studies at the University of York.

If Zuma is deposed before December’s ANC congress, Baleka Mbete, speaker of the National Assembly since 2014 and the ANC’s national chairperson, would constitutionally assume the position of acting president. She officially made herself available as a presidential candidate in January, but was unpleasantly surprised when the ANCWL announced that Dlamini-Zuma was its preferred candidate.

Mbete, 68, lived in exile during the 1970s and 1980s, working in Tanzania, Botswana, Zambia and Kenya as administrative secretary for the ANC national executive. Elected as an MP after South Africa’s first democratic election, in 1996 she became deputy speaker, then speaker in 2004. A school teacher by training, she has no experience of running a government department, and according to political analyst Prince Mashele, has “no clear constituency”.

“She has also not acquitted herself well as speaker,” says Mashele, adding that she has been embroiled in several scandals, including allegations that she obtained a fraudulent driving licence and enjoyed “subsidised travel privileges”. “She doesn’t have the personal integrity needed for the role of future president,” Mashele comments.