Statutory rape has swept South Africa over the past five years as evidenced by the number of girls aged 10 to 14 years giving birth at public health facilities, which has soared by almost 50%. It is a healthcare crisis worsened by children confined to home under pandemic lockdowns.

The study from which this alarming statistic is derived, ‘Teenage Births and Pregnancies in South Africa: a Reflection of a Troubled Country’, by a research team headed by Dr Peter Barron of Wits University’s School of Public Health and published in April in the South African Medical Journal, comes against a backdrop in which the country has long scored poorly on the protection of the child.

“Although the numbers of deliveries in this group are relatively small,” the study says, “each one represents a failure of society in general and … a personal tragedy for the girl and family involved.”

The report was conveyed to parliament and covered by the media with alarm. But Barron’s figures cover only the approximately 85% of deliveries that occur in the public sector, and revealed that from April 2017 to September 2021, in addition to public facility births for girls under 14, for “older teenagers aged 15–19, the number of deliveries increased from 114,329 in 2017/18 to 134,267 in 2020/21, an increase of 17.4%”. Population increases in these age bands of 8.8% and 2.9% respectively simply cannot account for these figures.

A Covid-19 “scorecard” released last year by Accountability International, a Cape Town-based research and policy advocacy non-profit organisation, which provides observers such as the UN Development Programme and donor agencies with statistic-based ratings on how African countries perform in key universal healthcare policies, noted with concern that children across the continent face an enormous and diverse phalanx of threats.

The scorecard warned that “entrenched patriarchal, ageist and sexist attitudes within both traditional African and imported colonial traditions have laid the foundations for and further enabled modern versions of child abuse and exploitation. These include contemporary forced-labour trafficking, child soldiering, and child-sex tourism” as well as child-rights abuses and failures such as child marriage and child poverty.

The study’s researchers write: “While most countries have national laws against statutory rape, (having sex with children under the legal age of consent to engage in sex), perceived enforcement levels are not always high. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNCHR), children seen as ‘victims’ of abuses are more likely to be treated as passive objects of welfare rather than as rights holders.”

While child rape is universally condemned, other sexual abuses of children, particularly the child-sex trade and child marriage are rooted in adult cultural acceptance. While not common in South Africa, the cultural enabling of paedophile-predator tourism is alarming in Kenya, where anti-child-trafficking non-profit organisation Trace Kenya estimates there could be as many as 100,000 child sex workers in the coastal city of Mombasa alone, which accounts for almost a third of girls aged 12 to 18 in the region.

But as the Accountability International (AI) scorecard points out, children involved in sex tourism are not always trafficked. “They are often children who work on the street and go home at night, supporting their families with their earnings. What makes this problem more difficult to root out is its acceptance by many poor families who are reliant on the income derived from ‘transactional sex’ where the child receives – or is promised – food, money, shelter, drugs, or other assistance in exchange for sexual acts.”

AI also noted that “the local social acceptance of child prostitution/sex work is also driven by financial benefits to the adults who live off it – the owners of the bars and nightclubs whose under-aged clientele draws sex predators, the taxi drivers who take payments for taking tourists to such spots” and so on. A 2018 Reuters report on the Kenyan crisis said: “Deep-rooted sexism ensures deep-seated and daily discrimination, while ingrained customs from polygamy to early marriage leave girls and women disproportionately vulnerable.”

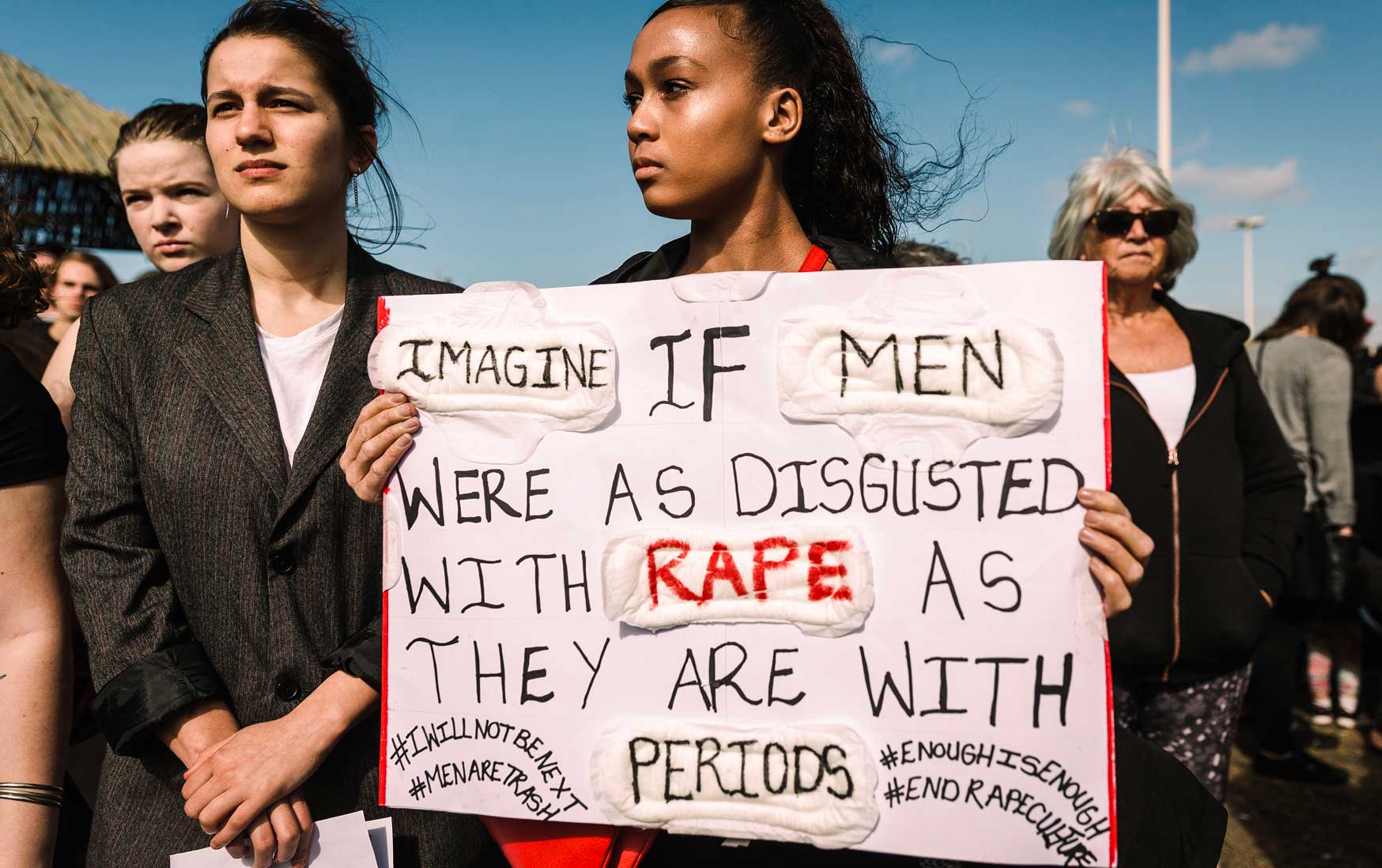

Though South Africa may be one of the African countries with the lowest child-marriage statistics, it has among the world’s worst figures for the sexual abuse of children. Last year’s annual police statistics revealed that more than 24,000 children under 18 – the UN age of majority – were reported to have been raped in the previous year, and that almost a third of all girls would experience some form of sexual abuse before the age of 18. This grim picture is incomplete, however, as crime stats are based on reported and investigated incidents only.

As early as 2013, a study by OA Oyedele et al, in the African Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, looking at ways to prevent teen pregnancies, noted that “the need for attachment is the basic reason why teenagers seek sexual relationships in order to establish interpersonal relationships”.

This security-seeking behaviour by poor girls blurs into so-called “blesser culture” in South Africa, where schoolgirls earn money, cellphones, clothes and other luxury items, and sometimes trips abroad, for engaging in transactional sex with older, usually financially secure sugar daddies, the “blessers”. Long a common underground feature of South Africa’s patriarchal society, it emerged into the light of day via social media in 2016 with the founding of the Facebook group Blesserfinder.

Today the group has more than 9,100 followers, including one who unsubtly calls herself Sugar Babelove, with one blesser stating he would be visiting Durban and offering R3,500 ($210) for unspecified services. A female blessee, meanwhile, posted a picture of a fistful of large-denomination banknotes, boasting: “My blesser came through for me”. The site – which has previously denied charges of promoting prostitution – states baldly: “Morals will never pay your fees.”

That attitude, says child sexuality specialist Prof Deevia Bhana of the University of KwaZulu- Natal, is part of the normalisation of how girls are mistreated in South Africa’s “horrific, criminal gender war”, which is enabled by “a very toxic and harmful environment” in which a misogynist and ageist authoritarian culture entrenches “male sexual entitlement”, especially among older men, and leads to “male sexual violence against young girls”.

Bhana also argues that traditional practices supposedly to protect girls’ virginity may contribute to this. “Some girls in KwaZulu-Natal go to the Reed Dance, a Zulu coming-of-age ceremony”, she says, “and have virginity testing done monthly to protect themselves from HIV and unwanted pregnancy.”

However, Bhana has found that virginity and virginal status are regarded as a prize, idealised, and pursued because of notions of sexual innocence, whereas girls who are not virgins are seen as “gold-diggers” and stigmatised. “This is shown by the larger statistics in terms of teen pregnancy in rural areas,” she says.

Bhana points out that spatial issues grounded in apartheid and poverty also produced conditions where there was often no privacy from the gaze of adult men for young girls in single-room shacks. She warns, however, that the scale and detail of the underaged pregnancy crisis is tough to assess; despite the fact that she herself has spent 24 years in the field, it is exceptionally difficult to do adequate research, especially among 10-14 year olds.

A pregnancy at 14 years or younger often involves statutory rape and, if so, researchers are obliged by law to breach their professional ethics and report the male perpetrator to the police. The inherent potential conflict of interest means that researchers have conducted almost no research into exactly who these fathers are, whether they are “age-appropriate” young boys, or adult fathers, stepfathers, caregivers, neighbours, strangers or teachers. And the data gap stretches back decades, so there is no real picture of how the problem is evolving.

The impact on homes with child-mothers is dire. Even if the girl survives the medical complications of premature pregnancy and if the baby itself is not murdered or dumped, her chances of completing schooling and having a normal youth become remote. Mothers under 15 cannot access child-care grants as identity documents are only issued at 16, while the care of surviving babies is usually entrusted to grandparents who are themselves often in their thirties – and so too young to access the senior citizen’s grants on which so many poor families depend.

This is worsened, Bhana says, by teachers’ unwillingness to report underaged childbearing as they are obliged to by education department rules, for fear of ostracism and victimisation in their communities – and of violent, potentially murderous reprisals by a perpetrator that is most likely known to them. The families of child-rape victims also tend to close ranks around perpetrators who live in the household as they are often the sole breadwinner and there is a fear of the family imploding and losing its livelihood should the perpetrator be arrested.

Meanwhile, Barron and his colleagues conclude that their findings “pose serious questions to society in general and to the health, education, and social sectors, as they reflect socioeconomic circumstances (e.g., sexual and gender-based violence, economic security of families, school attendance) as well as inadequate health education and life skills and access to health services. The country has much to do to reverse these negative trends.”