A great power competition has returned to centre-stage of the geopolitical landscape between the US and an emerging China. Constant technological advancement and global connectivity in the digital space are critical in shaping the outcome of this competition, ultimately determining the modern international order.

Africa has an urgent need for infrastructure development. Infrastructure is vital for sustainable economic development and provides efficient ways to achieve greater productivity. The lack of capital for infrastructure, in all its forms, has created a complex undertaking for most African nations. There is a lack of basic telecommunication and a need for upgrades to existing infrastructure to continue being relevant in the digital age.

This digital transformation is paramount to solving Africa’s enduring social and economic challenges. China can approach African heads of government to end the challenges many nations face. The US faces numerous handicaps, among which are Africans’ aspirations to maintain sovereignty while achieving economic growth. Sovereignty, defined by African leaders, is about survival without major interference.

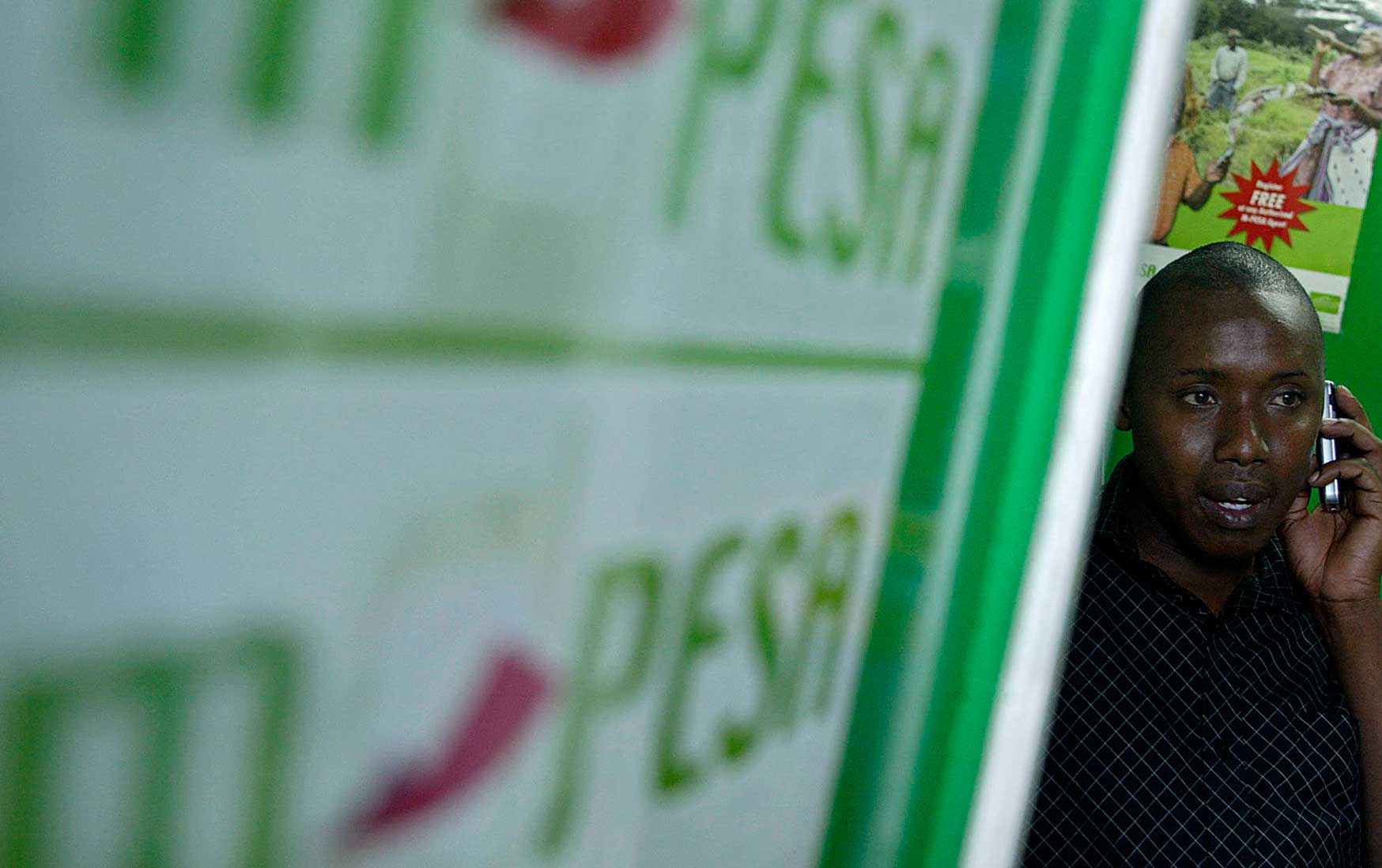

The M-Pesa cell phone banking system, dependent on Huawei’s Mobile Money platform, has assisted millions of Africans to move into the formal financial system. Photo: Tony Karumba/AFP

The trade war initiated by former US president Donald Trump has led to the US-China competition underway today. While US government officials have claimed it was about trade imbalances, in reality, it is a global battle for technological leadership and dominance. Washington’s true objective is to hamper China’s growing influence by using trade embargoes to frustrate China’s technological expansion. The US-China trade war has evolved into a tech war, whereby the nation-state that gains control over the technological sphere can generate significant headway for achieving geopolitical aims, from economic prosperity to military superiority.

The competition over information technology draws parallels from historical tussels between the great powers. For example, US and Soviet Union efforts to win the space and nuclear arms race share similarities with the current China-American technwar. The central concern in all these forms of competition narrows down to which system of governance will triumph. Without direct hostility and conflict, China challenges American global power through digital competition.

Beijing endorses an archetype of state-led capitalism and political illiberalism as a rising power, posing a threat to the US’s liberal-democratic ideas. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s communist autocracy benefits from the efficiencies of direct development; government and industry work together for and under the same leader. Technological authority in the US, by comparison, requires a collaborative approach between the private sector and government. The scope of China’s technological advancements underscores the repercussions of the US’s overall declining economic monopoly.

The tech race is also a contest of whether the US or China will set the standards of digital governance. Technological modernisation has accelerated the race from 5G, Big Data, Internet of Things (IoT), and satellite navigation to robotics, biotech, aviation, agriculture, artificial intelligence (AI), and clean tech. In recent years, the flash point of antagonism has been the rise of 5G technology and its role in shaping the fourth industrial revolution.

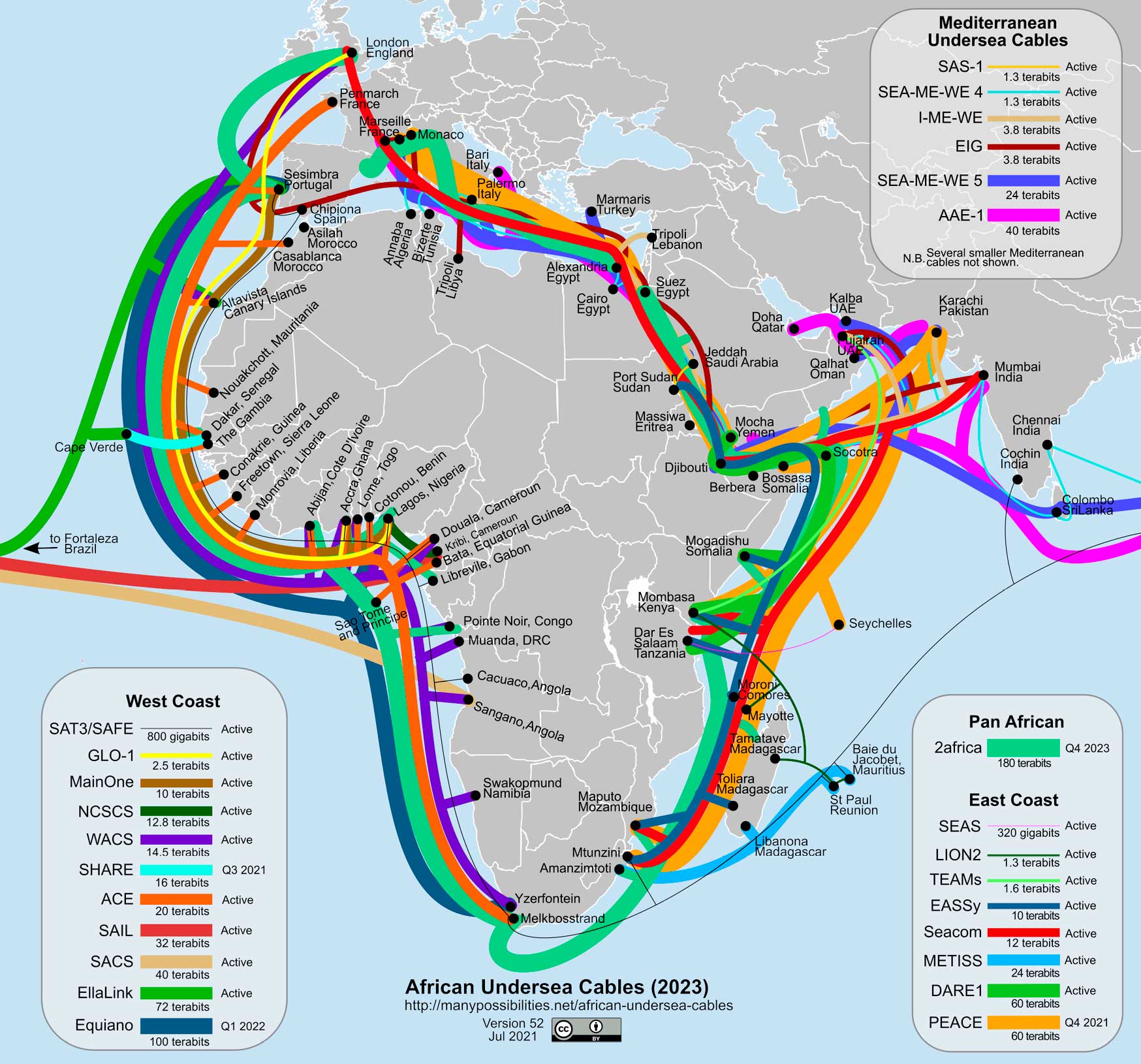

The proposed African undersea cable network layout as planned for 2023. Image: flickr.com/photos/ssong

China’s significant headway in the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) arena is being championed by Huawei; a world leader in equipment and mobile sales. The importance of the ICT sector between the two powers is the knock-on effect on other leading sectors of geopolitical power. The perceived winner of this clash will ultimately be accredited with augmented positive results economically and militarily.

The Digital Silk Road (DSR) is part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that is focused on enhancing digital connectivity abroad. The DSR acknowledges that technological dominance will play a vital role in boosting military and economic power in the future. Chinese companies collaborate with their own and African governments to secure and provide substantial infrastructure funds, loans, and assistance to nation states in dire need. These support mechanisms hold no political or economic conditions, making them extremely attractive to a continent that pursues sovereignty for its survival. China’s support and hands-off approach are attractive to African nations’ quest for development.

The colossal breadth of the technological engagement between China and Africa goes back decades. Africa experienced a telecommunications revolution in the 1990s. Coinciding with this, Chinese firms flocked to the continent to create ties with governments and support infrastructure upgrades. These ties gathered further momentum from the 2000s onwards.

The continual support, expansion, and enhancement of technological infrastructure in the African market witnessed Chinese tech companies permeate all layers of Africa’s telecommunications sector. From undersea cables, satellites, and backbone infrastructure to applications and platforms for individual customers, Chinese ventures across the continent have heightened optimism that the socioeconomic ills vexing African countries can be fixed. Beijing’s infrastructure development programmes are significant for the advancement of Africa as they boost long-term economic growth and development, increase productivity and attract capital by facilitating market access.

African internet penetration lags behind the global average of 35.2%. Chinese companies provide indispensable support to African nations through competitive pricing, low production costs, cost-effective equipment and solutions, and access to Chinese state-subsidised funding and support. Huawei, heavily supported by the government, is a crucial component of China’s involvement in the digital sector. Rural towers and mobile phones have brought internet access to remote African regions.

Moreover, the M-Pesa cellphone banking system, dependent on Huawei’s Mobile Money platform, has assisted millions of Africans to move into the formal financial system. Such infrastructure enables countries to exploit novel opportunities to achieve universal access and participation in the global economy, catalyse the growth of enterprises, improve productivity and services, and enhance health care, disaster management, and logistics.

Beijing has and continues to offer Africa substantial infrastructure funds. Instead of focusing on traditional aid, Xi Jinping and his government have found innovative ways to support a continent in need. The Chinese approach to Africa has been received with open arms by governments who need new solutions to existential and enduring challenges that the US has disregarded for years.

Safaricom’s M-Pesa service in Nairobi, Kenya. Photos: Vodafone Group/Philip Mostert/pmphoto.co.za

The US has never had a fully-fledged playbook for the African continent and the Biden administration is no exception. For as long as the US has been involved in Africa, ambassadors run day-to-day operations, individually tailoring their approach to the continent’s 55 countries. Ambassadors are the primary decision-makers, who receive support and direction from the State Department in Washington. American mission chiefs collaborate with African heads of state, creating a gap between the upper echelons of the US government and its African counterparts. This approach entrenches coordination issues that have been prevalent for years. Likewise, the US government has floundered in addressing the lagging economy and investment concerns that face most African nations.

Overall, America does not have a tech strategy for Africa, mainly because it does not have one for itself. Beyond leveraging economic and intelligence-sharing partnerships with allies to minimise China’s global technological influence, the US has failed to evolve a calculated strategy. Rather, the American capitalistic private sector drives the US technological footprint in Africa. African companies and governments work directly with US counterparts on research and development. Beyond American private investment into specific technological industries, the US has done little to address or strengthen Africa’s information technology sector. US engagement on the continent primarily follows political and humanitarian concerns, instead of focusing on the overall upliftment of Africa. Thus, traditional aid is abundant through humanitarian assistance, election monitoring, and the containment of infectious diseases and terrorism.

Though generally not expressed as crassly as it was by Donald Trump, the standard US narrative about Africa is substantively not much different from how he characterised it. So far, the Biden administration has maintained significant policies and policymakers’ general approach from the Trump era. The US also uses its position in international organisations to support Africa more broadly. For example, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) approve African countries for loans and infrastructure programmes with conditions that support a US-led global order. This aid and support are essential. However, there is a lack of attention on the long-term upliftment and to end of the socio-economic miasma that plagues Africa.

China, however, has been able to reflect African realities in its political playbook. Instead of ignoring African preferences and policy priorities, China has begun to address the socioeconomic conditions challenging Africa. In turn, Africa, which does not have the self-sufficiency to adequately promote social and economic development, welcomes China’s unconditional assistance.

So, as the rivalry between the US and China escalates, Africa will be one of the most important theatres and potential benefactors. China has the upper hand. Instead of engaging with a continent in need, the US has continued to implement policies that do not prioritise African preferences. China has stepped in, created relationships, and wrought progressive transformation. Unless there is a shift in US policy, China’s advancement of Africa’s ICT sector will leave the US trailing substantially behind.

[activecampaign form=1]