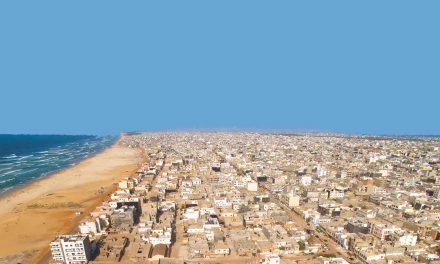

A female farmer in the Drakensberg, KwaZulu-Natal. Photo: Hansm/Wikimedia

Although often complicated by vested interests, decentralisation should be a two-way process between national government and local authorities

In rural KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa’s most populous province, women still cannot get allocated land under their own names. “Out of 300 traditional leaders that I know, only two allocate land to women in their own right and have that land registered in the name of the woman,” says Sizani Ngubane, the founder of the Rural Women’s Movement, a lobby group operating across KwaZulu-Natal (KZN).

It also doesn’t help that some 2.8 million hectares of land controlled by the Zulu king is only available to rural communities under lease agreements that attract an annual 10% escalation fee.

However, activists, including Ngubane, are challenging this arrangement, which many say only serves to enrich the king – who is also a recipient of generous state subsidies for the upkeep of the royal household.

These are startling details, given South Africa’s constitutionally enshrined liberal values of equal access and fairness. The Rural Women’s Movement argues that devolved spaces, outside of governmental strictures, are necessary for social justice and the capacity of citizens to exercise their rights and responsibilities. “People are in fact calling for further decentralisation,” says Ruth Hall, a professor at the University of the Western Cape’s Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies.

Elsewhere, Zimbabwe’s main opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) is contemplating a related problem. “The emphasis of central government and (the ruling) Zanu-PF has been to restrict the capacity of all local authorities under MDC control to succeed,” says MDC MP Eddie Cross. “Streams of funding have been withdrawn, and the state has refused to even disburse the funds allocated in the constitution.”

The hollowing out of local government in Zimbabwe represents another facet of the argument for decentralisation. Around Africa, local government and traditional rule in rural areas are increasingly being contested. And in some cases, the power structures that are available are occupied by groups and parties in opposition to central authority. Sometimes those contesting power in these spaces also complement central authority.

Since its onset in 1999, the MDC has faced mammoth obstacles in its quest to take state power, largely due to Zimbabwe’s skewed electoral laws and a clampdown on the opposition under former president Robert Mugabe, who was ousted from power in November 2017. The new constitution of 2013 includes recognition of the need for devolved authorities. It envisages the creation of provincial councils as the second tier of government to include all MPs and senators, mayors or chairpersons of local councils per province.

“We (the MDC) have had devolution as a main plank of our own policies, but apart from winning the concession in the 2013 constitution we have been unable to shift government policy,” Cross says. Meanwhile, Zimbabwe has yet to implement the new provision. And the government is seeking a constitutional amendment that would place local authorities under an appointed minister of state, he says.

This has left it to activist groups to make their voices heard. One of these is the Habakkuk Trust, a Christian civil rights advocacy organisation based in the country’s second largest city, Bulawayo, which is lobbying the government to implement chapter 14 of the constitution, which focuses on devolution. “In cities such as Bulawayo it is clear that if local authorities are given more power they deliver more,” says the trust’s chief executive officer Dumisani Nkomo.

An underlying problem, however, is that the state in Zimbabwe is essentially broke and hence unable to meet many of its financial obligations, including disbursements to local authorities. One effect of weakened state capacity has been a mushrooming of alternative service-provision structures run by residents – a forced devolution of sorts. For example, residents’ associations are now involved in repairing roads and street lights, among other services, to keep MDC-controlled Harare running.

Spokesman for the Harare City Council Michael Chideme says: “We have decentralised our services to the grassroots to empower residents to decide with council the priority areas they want.” Service-delivery complaints are handled at local level. For example, “employees doing the water and refuse jobs report to the local council district officer, who allocates work on a daily basis and is accountable.”

A similar approach to managing local affairs has been taken in South Africa by the residents’ association of one of Johannesburg’s wealthiest suburbs. The association attracted newspaper headlines when it confronted the Gupta brothers – President Jacob Zuma’s friends – over allegations that their massive home infringed council by-laws. Five years on, the matter is set to go to court after the association challenged the council approval.

Tessa Turvey, the chairperson of the Saxonwold and Parkwood Residents Association (Sapra), says its mandate is to alert the Johannesburg city council to by-law transgressions, many of which might well be due to ignorance. “The advantage is that we are on the ground and we are living in the area, we understand the dynamics of the issues,” she says.

Underlying Sapra’s work is protecting residents’ property values. But Turvey’s attitude to self-organisation includes a more general view of the importance of community involvement. “In all areas people need to stand up and say ‘this is my street, this is my home’. You’ve got to be an active participant in your city.”

Like Zimbabwe, Zambia also faces constraints in the lack of political will to allow for constitutionally mandated devolution. Successive Zambian governments have paid lip service to the idea of decentralisation to the local level, says Neo Simutanyi, executive director of the Lusaka-based Centre for Policy Dialogue. “If anything, Zambia’s local-government story is one of central government using the local government institutions as an extension of the centre and site of patronage,” he told Africa in Fact.

But the similarities with Zimbabwe end there. “The problem with devolution of power in Zambia is that it has tended to be promoted by donors,” Simutanyi says.

This is a view shared by Patrick Bond, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Governance in Johannesburg. He argues that the impetus toward decentralisation on the continent has mainly been driven by powerful ideologues of neo-liberalism at finance ministries and higher up at the Bretton Woods institutions, who are committed to cutting state expenditure that addresses the needs of poor people. “For these people, decentralisation is extremely useful,” Bond says.

In South Africa, he goes on, budget cuts that limit the capacity of lower-tier government are sometimes hidden behind “unfunded mandates”, by which a province, metro or municipality will be required to provide more services, but with fewer resources. “Many municipalities then suffer a ‘race to the bottom’ as their decentralised economic power leads to a ‘local economic development’ strategy – for example, to set water and electricity tariffs at very low levels so as to attract new investors,” Bond told Africa in Fact. “That often goes belly up, or requires cross-subsidisation from the rest of the city’s rates base.”

The high levels of service-delivery protests in South Africa can be seen as an example of locally based activists contesting these decentralisation tendencies, he adds. But he suggests that, while their dissent has been widespread, their lack of ideology and interconnectedness with other local struggles results in “popcorn protests” that fizzle out almost as soon as they arise.

This despite the fact that decentralisation has taken a firmer root in South Africa than it has elsewhere on the continent, thanks to constitutional guarantees on devolution, which determine a number of tiered government levels. Section 195 of the constitution spells out the different levels of public administration and emphasises that “people’s needs must be responded to” and that “the public must be encouraged to participate in policymaking”.

This has led to a strong ethos of involvement by citizens, ranging from participation in school governing boards, that represent the interest of parents, to clinic committees in rural areas, observes Mark Heywood, head of the NGO Section27. Where decentralisation fails, this is often due to communities’ ignorance of the constitution, more than anything else. “People don’t know their powers and they don’t know their rights,” says Heywood.

Among the most successful community actions was the mobilisation by residents of Matatiele, a nondescript rural backwater, over a municipal demarcation dispute. The community’s demands for re-incorporation into KZN, from the poorer Eastern Cape province, led to the formation of a political party that contested municipal elections in 2016 to fight its cause.

Yet in South Africa as elsewhere in Africa, traditional authorities have been among the most controversial. “One of the big questions is: are they accountable upwards or downward?” Hall asks. Her answer concedes that this depends – on a case-by-case basis.

One vexing issue is the claim among some political pundits that poor rural women are among the least organised groups on the continent – with the unemployed being even less organised. Nomboniso Gasa, Adjunct Professor at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and a gender activist, says this view is “ahistorical”.

Nokwanda Sihlali, a research officer at UCT’s Land and Accountability Research Centre, agrees. Since the advent of democracy in South Africa, she says, African women have been the agents of change in their own lives, having fought within their communities for their rights on customary marriage, inheritance, and succession to traditional leadership.

Ngubane marvels at how far the women’s lobby has come. When she started the Rural Women’s Movement in 1998, a widow was not allowed to enter a traditional court – a space reserved for men. Instead, her testimony was taken by a man from across the perimeter fence. “Whereas at the time women couldn’t speak in public, we are now not only speaking in community halls, today we are speaking at international level as well,” she told Africa in Fact.

Notwithstanding such shifts, there are limits to the benefits of decentralisation, which, crucially, depends on local empowerment on a number of levels, including education and funding. Heywood is a strong believer in lower levels of democracy, provided that communities are properly informed of their powers and the processes involved, and that national and provincial governments continue to provide oversight to maintain standards. “There is no contradiction between a strong state at national level that regulates such areas as health, education and labour, which is pushing power down to the people for it to be exercised at the local level,” he says.

Bond offers the idea of “subsidiarity” as a counter to notions of hierarchical dependence in governance systems. As he understands it, this means “scale politics”, in which some services are understood to be better if centralised and others better when decentralised.

Citing an example, Bond says it is now possible to have a very localised electricity grid due to renewable energy, whereas in past years the centralised grid was essential to ensure national coverage. However, the decentralised supply – even at household scale through photovoltaics – prevents a national-to-local cross subsidisation. So, while Germany successfully adopted the “feed-in tariff” to allow local-to-national supply of power, the system is highly regulated to ensure equity and access.

“This overall commitment to energy planning permitted the national government in Berlin to end its reliance on nuclear energy immediately after the Fukushima meltdown in 2011 without losing supply to its many heavy industrial electricity consumers,” says Bond, adding: “So in any such complex system, there is typically a mix of central and decentralised objectives and supply options.”

However, while many would like more local democracy and local control, if the scale of delivery requires “economies of scale” and “cross subsidisation”, then decentralisation can have terrible consequences, according to Bond. If all the wealthy households in a city like Cape Town started drilling their own boreholes or setting up solar systems without any corresponding increase in property rates, for example, the city council would have a much-reduced capacity to raise revenue, affecting services to consumers who cannot afford private ones.

“This is, indeed, why municipalities (in South Africa) united in anger when the regional electricity distributors – similar to water-catchment agencies – were proposed 20 years ago,” Bond says. “This is why they don’t like it when (power utility) Eskom provides direct electricity supply to their households or to commercial customers.” This removes the local supplier’s control, affecting its ability to move money to where it is needed and to exert pressure on the politicians, he adds.

Ultimately, decentralisation should not be seen as a one-way drive from the centre. Rather, it should be a two-way process. This will often be complicated by vested interests, as we have seen in the case of traditional authority structures and others that fall short on factors such as equality and openness. And it is these factors that lie at the root of many citizens’ grievances within modernising societies.

Yet around Africa, advances in education, along with better organisation, are leading to ever more pressure on powerful interests to concede and allow for sharing governance and decision making. In some cases, an uptake of technologies – such as digital communication in the form of mobile phones – is forcing a shift of power from the centre, giving citizens new choices and sometimes allowing for mutually beneficial cooperation.