UN Women estimates that 15 million adolescent girls worldwide have experienced forced sex. In Nigeria alone a 2014 national survey found that one in four girls experience sexual violence, defined as “all forms of sexual abuse and exploitation”, including rape.

Many African countries have made great strides toward achieving their development goals and protecting children, especially female children. The United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) has reported a decline in child marriages, child mortality and an increase in the number of girl children attending school. However, African girls still face often insurmountable odds, including sexual violence.

Sexual terrorism, according to research by Uyo Yenwong-Fai and published by the Institute for Security Studies, is “the use of sexual abuse to spread terror, to control or manipulate the government or parts of a population”. Suicide bombings, rape, and assault are part of a broader objective of spreading terror or sending a message. Acts that constitute sexual violence include rape, sexual mutilation, sexual humiliation, forced prostitution and forced pregnancy.

History illustrates that violence against women during conflicts is an ancient practice in which women were regarded as “spoils of war” owed to soldiers. Rape is one of the weapons of war and conflict, in which sexual violence is used to terrorise women and children and violate them. The abuse is not limited to women, but female children are especially subjected to terror. The rape of female children across African contexts is a tactic employed not only, though perhaps most infamously, by the likes of Muslim extremist group Boko Haram in Nigeria, but also by members of conventional armies and insurgents during wars and other forms of armed conflict.

In 2015 Amnesty International (AI) released a report titled ‘Nigeria: “Our job is to shoot, slaughter and kill”: Boko Haram’s reign of terror in north-east Nigeria’. The report detailed the abduction of an estimated 2,000 women and girls between 2014 and 2015, who were captured, raped, and forced into slavery by Boko Haram fighters. The kidnapping of the Chibok schoolgirls was just one horrifying example of this type of terrorism.

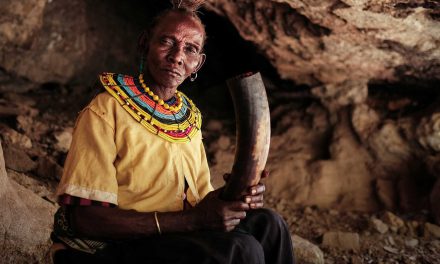

Some of the recently freed girls from Chibok wait in Abuja, Nigeria on May 7, 2017.

Rescued girls have detailed the gruesome acts they experienced, including being raped by up to six men. An AI press release from April 2021 notes that in the six years (then) since the Chibok incident, there is still “no accountability for crimes against children by Boko Haram and other gunmen”. AI country director Isai Ojigho indicated in the same release that in the three months leading up to March 2021 at least five cases of abductions were reported in northern Nigeria. The threat of further attacks led to the closure of 600 schools in the region. This is an example of how the general challenges faced by African girl children are compounded by extremism.

Sexual violence humiliates and destroys the social fabric of society, where a high premium is placed on the chastity of female children. Acts of terror have a devastating impact on the victims physically as well as psychologically. A 2018 report by the Global Coalition to Protect Education From Attack, titled ‘I will never go back to school’, details the impact of attacks on education for Nigerian girls. The authors note the pre-existing prevalence of child marriage in Nigeria (before the Chibok kidnapping in 2014). An estimated 62% of girls were married before their eighteenth birthdays.

Being out of school, a ubiquitous trend as a function of terror attacks, makes young girls more susceptible to early marriage. Christiana Attah, a lecturer in Jurisprudence and Public Law at Joseph Ayo Babalola University, Nigeria, writing in the African Human Rights Law Journal, says that the majority of victims of the Chibok kidnapping were impregnated, and many were also infected with STDs and/or HIV.

Amnesty has also reported that some of the women and female children rescued from the camps of Boko Haram militants have tested positive for HIV, and the majority of the rescued women were pregnant. Drawing on reporting by Adam Nossiter in the New York Times, Attah also noted: “The general opinion regarding the high number of pregnancies among the rescued female victims of Boko Haram’s sexual terrorism is that these pregnancies resulted from a deliberate plan to ensure that the women produce offspring that will continue the insurgency.”

Due to the prevailing culture of silence on matters related to rape on the continent, we may never know the full extent of the sexual violence Boko Haram and other extremist groups have unleashed on girls. Cases such as the Chibok kidnappings are only a few examples of the kinds of sexual violence that terror groups use against African girls. Many more cases remain undocumented, as the victims are too scared to come forward to seek help or treatment, which hinders efforts to tackle the problem. Despite this, some progress has been made in several countries.

In Burkina Faso, for example, armed Islamist groups have carried out abusive acts, including the rape of young women, as the young victims gathered wood, travelled to and from the market, and fled violence. A 2022 Human Rights Watch report documented several dozen cases of rape of women and girls by armed Islamist groups since 2016, most in the Centre-Nord region. The NGO interviewed 14 rape survivors, “many of whom had witnessed other women being raped”. It appeared, the report noted, that the intention behind this sexual violence was to extract information about government forces, and to convey ultimatums to villagers to abandon the area. Attackers also demanded that their victims display a knowledge of the Qur’an. Thus, while the controversy and risk of using the term “rape jihad” are understood, one also cannot shy away from the reality of the explicit Islamic cause behind the acts, as misguided as others might argue that to be.

Current efforts to protect girls from sexual terrorism have been insufficient due to the absence of criminal justice responses. Attah explains, for instance, that the Nigerian government’s enactment of the Terrorism Prevention Act of 2011 and amended in 2013 is silent on the use of rape to further the ends of terrorist groups: “By not making any reference to the use of rape as a terror tactic, the Act appears either to have glossed over the possibility of rape being used by terrorists, or chosen to ignore it in line with the culture of silence surrounding rape in Nigeria.”

Yenwong-Fai reports that UN Women, in northern Mali, partnered with NGOs in the country to assist women who had been raped or forced into marriage. Similar efforts exist in Somalia and Nigeria. Nevertheless, she adds: “Noteworthy as all these efforts may be, they are neither sufficient nor holistic enough to specifically address sexual terrorism.”

Countries often lack the infrastructure and resources to address terrorism and insurgency, making it more difficult to deal with abuses inflicted by the perpetrators. But special attention must be paid to the sexual abuse girls endure across the continent. Governments must strengthen the prevention of sexual terrorism by increasing awareness and security in remote and vulnerable areas, while also engaging with survivors, protecting them and encouraging victims to speak out.

From the kidnapping of girls to forced marriages of underage girls and female genital mutilation in many countries, it is tough being a girl in Africa. The continent owes its girl child a fair world, free from discrimination, violence, and access to a safe and secure environment.