“I was entrusted to a woman who wanted a servant in Cotonou. I got up at 5am and worked about 18 hours a day. I spent two years with my employer without being able to speak with my parents. I suffered a lot of physical abuse until the day I decided to flee. I came back to Togo thanks to the help of someone from our neighbourhood, who is also a Togolese national living in Benin.”

Twelve-year-old Adèle Tchodié was a victim of trafficking and still bears the psychological and physical scars of her ordeal in Benin, where she was entrusted to a woman called tata or “mistress” to work as a servant.

Adèle explained that the woman had come to their village and introduced herself as a close relative of her uncle’s wife, offering to take the young girl to Benin to help her learn tailoring.

“It was with this promise that she succeeded in convincing my parents to entrust me to her,” Adèle, who was only 10 at the time, explained.

This testimony is a reminder that more than 700 young children, mostly girls, from this West African country are victims of child trafficking every year, according to RELUTET, a network created in 2015 that brings together 45 civil society organisations to campaign against child trafficking

The Social Reintegration Centre for Victims of Child Trafficking, set up by the children’s rights NGO known as CREUSET, which is based in Sokodé, about 400 km from Lomé, the Togolese capital, welcomes and helps reintegrate child trafficking victims. At the time of writing, in October last year, the organisation said it had recently accommodated dozens of victims.

Every year, through coercion and deception, hundreds of young Togolese girls and boys are lured by the prospect of jobs and better living opportunities in destination countries. The modus operandi of recruiters remains the same throughout the country, though villages in the central and Kara regions of the country are most affected by these illegal activities.

Recruiters generally target extremely poor families with several children, first gaining the confidence of the victims’ parents, who entrust their children to them in the hope of a better future upon their return.

As RELUTET project assistant Yao Dogbé notes, about two-thirds of the victims are girls aged 10 to 18. “Recruiters pretend to be close family members; they also introduce themselves as Togolese citizens concerned about the well-being of their fellow citizens back home,” he says. “Thus, they manage to conclude agreements with the families of the victims.”

In 2021, for example, a 65-year-old woman recruiter in the company of six Togolese girls was arrested by Ghana immigration services in the border village of Natchamba. She was trying to transport the victims, aged 6 to 15, to Kandia, a village in the savannah region of Ghana, where they were to be employed as field workers.

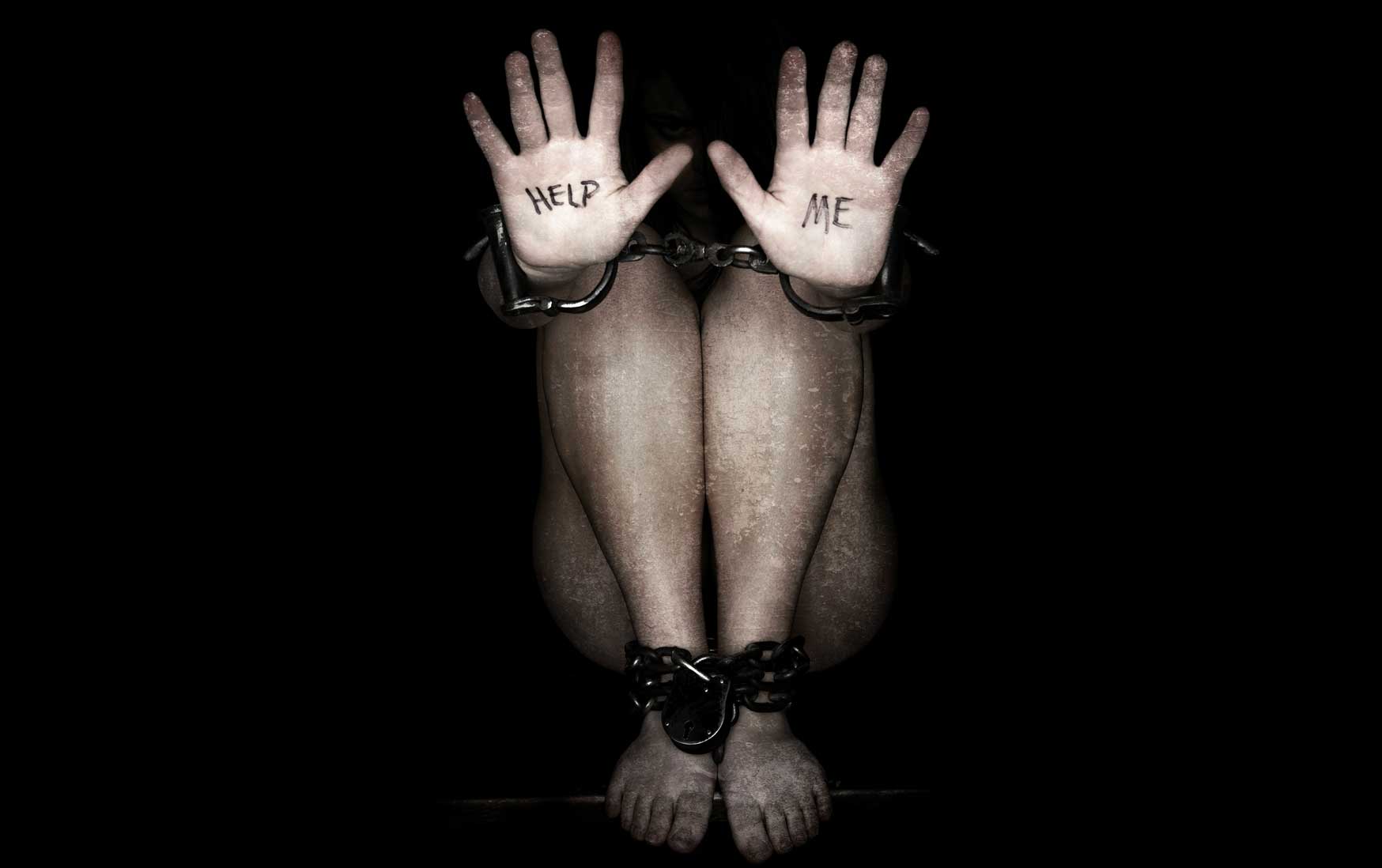

Dozens of enslaved children in the back of a police vehicle after they were stopped at the Seme border en route to the Republic of Benin. Photos: STR / AFP

Some boys, tempted by the adventure promised by recruiters, who dangle work opportunities in neighbouring countries, leave with traffickers without parental approval. This was the case with Pyabalo Tchalim, who was recruited by the uncle of a former classmate. The young boy, now 15, spent four months in Nigeria working as a labourer on a plantain farm. Today, he regrets this hazardous trip, which resulted in physical injury. He did, however, return home with a bicycle for the work he did during his stay.

“We were forced to work even in the pouring rain, because the employer wanted the work to [be done] at all costs. Today, I find myself without the thumb of my right hand,” he told Africa in Fact. “I wanted to come back home, so I can go back to school, but I couldn’t because of my physical disability.”

Togo’s trafficked children do not end up only in neighbouring countries such as Ghana, Benin, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon. According to human rights organisations, older victims, mostly girls, end up in Middle Eastern countries such as Lebanon.

Pastor Edoh Komi, the executive director of a human rights organisation, Voice of the Voiceless, confirms that they have received dozens of distress calls from young Togolese girls working in Lebanon.

“The last one was the victim of sexual harassment by her employer,” he told Africa in Fact. “Our organisation has received several cases of complaints of sexual harassment against employers.”

Togo’s Director of International Relations at the Ministry of Labour, Ayawavi Galley-Agbessi, agrees the problem is serious. “We need a lot of resources to fight human trafficking,” he says. “We will intensify awareness campaigns in the areas most affected by this phenomenon, which deprives children of their fundamental human rights such as the right to education and good health.”

Since 2010 the authorities have taken several measures to act against human trafficking networks, including a much closer collaboration between the immigration services and their counterparts in neighbouring Ghana, Burkina Faso and Benin.

Controls have been strengthened at land border posts to track down recruiting agents, but, faced with the scale of the phenomenon, the authorities have also initiated partnerships with actors such as civil society organisations and traditional and religious leaders in the most affected areas in the north of the country. A national commission was also set up in 2021 to coordinate all actions aimed at combating child trafficking, while in June last year the country also carried out a national awareness campaign aimed at discouraging child labour.

Togo has also strengthened its legal arsenal to protect children against any practice detrimental to their development. Article 319 of the new penal code adopted in November 2015 provides that any person who commits, or is an accomplice to, human trafficking incurs a sentence of 20-30 years’ imprisonment and a fine of 20-50 million FCFA (about $32,000-$80,000). The country has also recently set up a helpline – ALLO 1011 – to allow citizens to report cases of child trafficking and to seek care for victims.

The Minister of Social Action, Promotion of Women and Literacy, Adjovi Lolonyo Apedoh-Anakoma, says the government will also further strengthen actions to guarantee a more protective environment for children.

However, despite all these measures, by the authorities and in collaboration with civil society, child trafficking persists due to poverty in the affected areas of the country.