Amazed young woman touching the air during the VR experience. Horizontal studio shot.

Here’s a remarkable fact: the gap between the average age of rulers and the median age of the ruled is highest in Africa – at 62 and 19.5 respectively. This situation “raises concerns about how well decision makers understand the needs and aspirations of young people,” Mohamed Yahya, the regional programme coordinator with UNDP Africa, writes in a 2017 article. As he points out, Africa has the youngest population in the world, and it is growing fast.

“By 2055, the continent’s youth population (aged 15-24) is expected to be more than double the 2015 total of 226 million,” he says, “yet the continent remains stubbornly inhospitable – politically, economically, and socially – to young people.

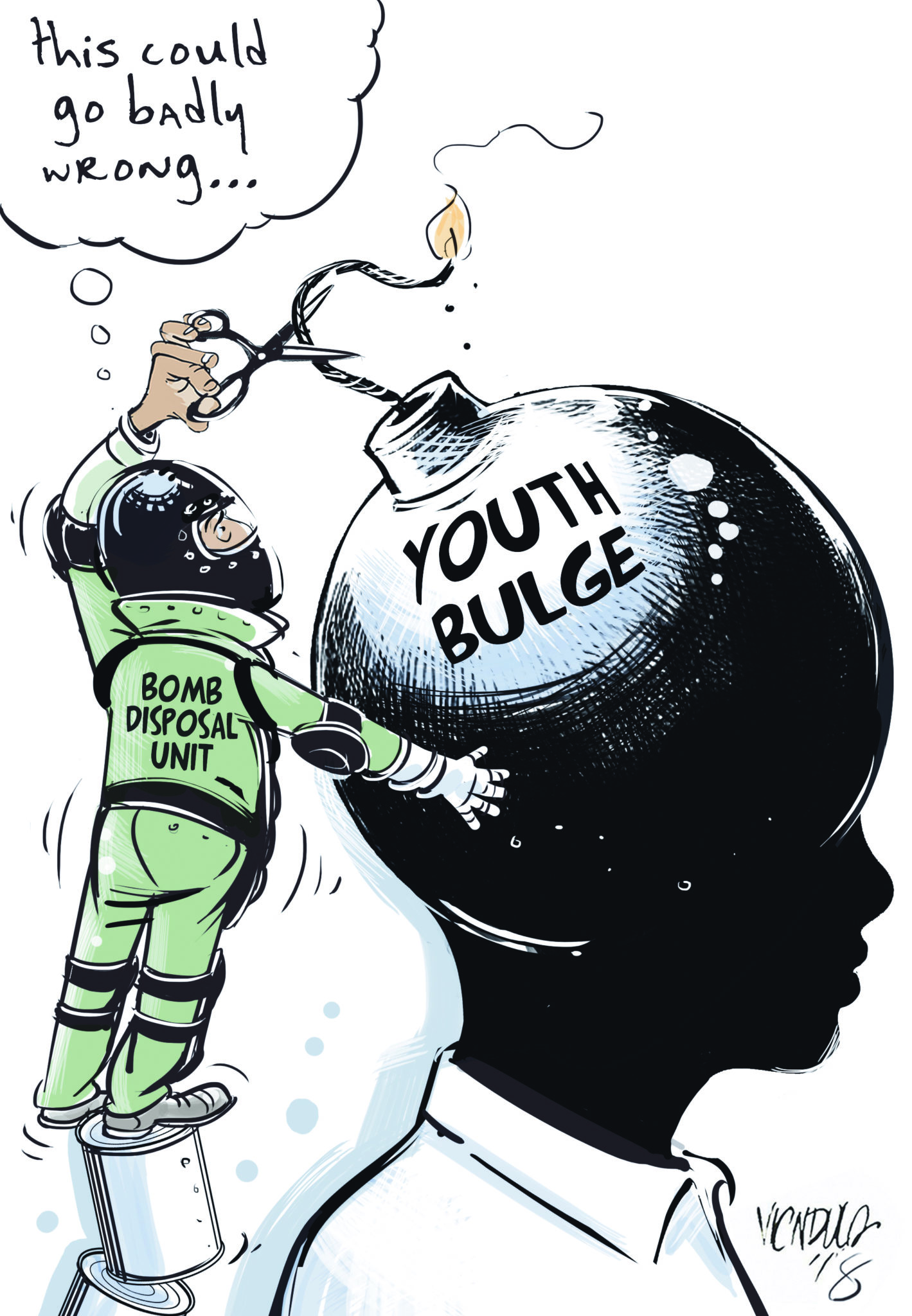

The success of African governments’ efforts to address this will be the single most important factor determining whether the continent prospers or suffers in the coming decades.” The African Development Bank goes further, warning after a governor’s meeting in March that the continent’s growing youth unemployment is a “ticking time bomb”. According to the bank, 12 million young people entered Africa’s labour force in 2015, but only 3.1 million jobs were created in that year.

“That means that millions of young people were left without a stake in the economy,” comments Yahya. Meanwhile, the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) currently sweeping the world will bring about a revolution in the way we work, pundits say, and forever change the nature of the jobs we do. Given the continent’s relatively poor education provision, Africa is likely to be one of the most dramatically affected regions. As with other work-related revolutions, contentious predictions and perceptions abound.

The most hysterical of these is that artificial intelligence (AI) will take over many jobs that humans presently do. But right now AI is far from being as efficient as a human brain at many functions, except some narrow, clearly defined tasks. Current AI-type projects are better understood in terms of “machine learning”, because that is really what they are. A handy way to understand this new wave of AI-like services and tasks is to see it as an extension of the automation we saw in the preceding revolutions.

During the Second Industrial Revolution, it was found that repetitive jobs could be done more effectively on production lines: think Ford motorcars in 1904. The Third Industrial Revolution (3IR) was ushered in with the rise of computers, which brings us ultimately to Tesla’s fully robotic production line (ironically, Tesla has recently had to bring in humans to meet over-optimistic production targets). What is certain is that change is now as central a part of our world as work itself. Technology is influencing not just the type of jobs but the pace at which jobs are evolving.

The idea of the Fourth Industrial Revolution was first put forward in 2016 in a book of the same name by Professor Klaus Schwab, the founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, who wrote that he was “convinced that we are at the beginning of a revolution that is fundamentally changing the way we live, work and relate to one another”.

Arthur Goldstuck Image supplied

Arthur Goldstuck, MD of South African research organisation World Wide Worx, agrees. “AI will have a massive impact on jobs over the next 10 years,” he told Africa in Fact. “In just eight months in 2017, venture capital funding of AI start-ups doubled globally from $13.5bn to $27bn. This represents a fundamental shift in information technology – one that will change the shape of this industry and all others that use IT. It will be a tsunami that sweeps away numerous jobs, but leaves many new ones in its wake.”

There is a widespread perception that the rise of computers and digital technology during the 3IR that began in the 1970s has destroyed jobs. But numerous studies show that 3IR technology was a nett creator of new jobs – mostly jobs that the previous generation could not conceive of. “Less than a decade ago, nine out of 10 people worked in agriculture,” venture capitalist Michael Jordaan told Africa in Fact. “Over time, it became clear that machines like tractors and harvesters would destroy jobs in agriculture.”

However, it was far less clear then that new jobs such as portfolio manager, brand consultant, PR expert, Uber driver or software programmer would appear, he added. “It’s the same today. We can see that AI could take over some jobs or portions of jobs, but it is far more difficult to imagine the new ones, such as self-driving car engineer or social media marketing expert.”

Michael Jordaan, a former CEO of First National Bank, is a digital innovator whose bank won numerous global awards for innovation. In his view, some kinds of jobs will not be made redundant by 4IR, but will, rather, require the use of more technological tools. Accountants now use Excel and pilots use autopilot, for instance, he points out.

Michael Jordaan Image supplied

It’s a good point: accounting hasn’t gone out of business during any of the first three industrial revolutions, but the tools to do the job have gotten better. Goldstuck also points to the evolution of accounting.

His firm’s SME Survey suggests that accountants, for example, will become less important for bookkeeping and auditing and more important for business and tax advice. AI is already enabling a range of new approaches to familiar jobs, such as medical diagnostics and selecting shares to invest in.

NMRQL Research, a South African investment advisor, uses machine learning to enable unit trusts and hedge funds, while medical NGO pink ribbon/red ribbon is rolling out a mobile approach to diagnosing cervical cancer in six African countries. One job that is unlikely to go out of fashion anytime soon is software developer, or coder. Coding software is integral to the digital world in which we live. Software may ultimately make some functions easier to automate but it won’t remove the need for particular problem-solving skills, certainly not in the next five years. Coders are integral in our digital economy.

Developers are key to making software work, as former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer was famous for screaming while jumping around on stage. And coders are also an important key to new businesses trying to stake a claim in this Internet-enabled world. Andela, a stand-out African company that aims to address the skills gap in the developed world, is an example. It was launched in 2014 to address “the shortage of high-quality talent” in Africa, as its CEO, Jeremy Johnson, told Africa in Fact.

The firm has 550 developers who work as full-time engineers for some 100 partner companies, including Viacom, Mastercard Labs, Gusto and GitHub. One of its high-profile investors is the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative – a philanthropic organisation that “brings together world-class engineering, grant-making, impact investing, policy, and advocacy work”, according to its website – which invested $24 million. After making a surprise trip in August 2016 to Lagos, where Andela’s first office opened, Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, praised African entrepreneurs:

“The thing that is striking is the entrepreneurial energy. I think when you’re trying to build something, what matters the most is who wants it the most,” he told a gathering in Lagos, adding: “this is where the future is going to be built.” Andela last year raised another $40 million in Series C funding, bringing its total funding to $80 million, and has opened offices in Kampala and Nairobi. Johnson says the additional investment will enable it to double its staff of developers to 1,000 people.

“Over the past three years we’ve helped prove to the world that brilliance is evenly distributed,” Johnson said. “It’s now time to prove that our model of investing in extraordinary people isn’t just viable, but revolutionary. Increasingly, African technologists will be launching high-impact companies and solving some of the world’s most pressing problems.”

The average wage of a software developer in the United States is $112,000, according to PayScale, but this wage bill can be much cheaper in Africa, as Andela has shown. It’s not only about coders and coding, though. Google is hoping to train 10 million people for digital jobs, its CEO Sundar Pichai said in a surprise visit to Nigeria last year. “(We’re) thrilled that we’re expanding our digital skills programme to train 10 million Africans over the next five years,” Pichai tweeted, after Google had run a year-long programme to train one million people around the continent in digital skills.

“Having one million digitally skilled young people in Africa is good for everyone. Because we think that if young people have the right skills, they’ll build businesses, create jobs and boost economic growth across the continent,” Google South Africa country director Luke Mckend told Africa in Fact of this digital skills programme. Using an online portal and face-to-face training in 20 countries with 14 training partners, Google offers 89 courses covering topics such as digital marketing, effective social media use, optimising search terms, online sales and expanding a business internationally.

Jordaan’s advice is to “stop learning” and change the way children are taught. “The main thing is to teach kids to become multi-disciplinary, entrepreneurial problem solvers,” he says. “And for adults to embrace lifelong learning. We will be fine if we can adapt.” “The idea that AI spells the doom of humanity is clearly scaremongering,” says Goldstuck. He says he believes in humanity’s intuition and ability to solve problems, and argues that the doomsaying about the future of many jobs is an indication that we need to rethink education, focusing on the needs of the future. “Any job that can be automated will be, but there will always be room for problem solvers, creative thinkers and effective decision makers,” Goldstuck concludes.

Schwab – the first person to clearly identify the new trend – says the most important challenge to remember is that 4IR technologies must ultimately work for people, and not against them. “These new technologies are first and foremost tools made by people for people,” according to the WEF website. That is, they can help to shape the future by “putting people first” and using the new technologies to empower people. Digital skills are, therefore, becoming more and more central to economic survival, let alone progress.

Moreover, they can be self-taught: entrepreneurs around the continent are already seeing opportunities. But it’s not only up to them. The 4IR will also need a new approach to education, in the sense that the ability to self-learn in the digital space is dependent on background conditions of literacy, numeracy and familiarity with the way computers work. In Africa, that means that legislators and policymakers will need to understand the new trend not only as a challenge, but also as an opportunity.