“Down with Mubarak” @Mona

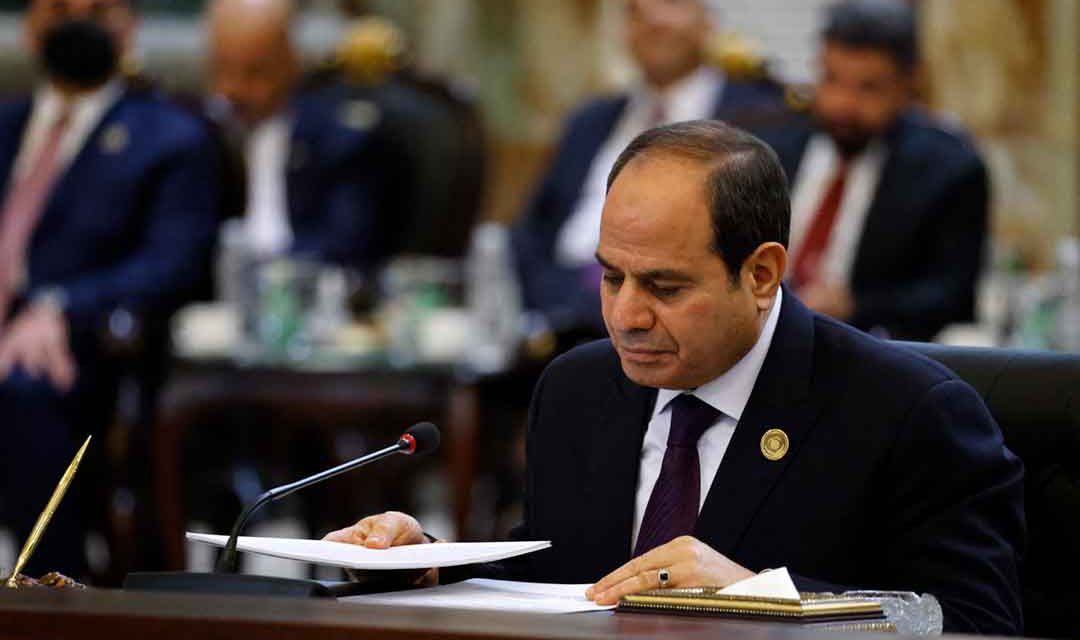

Since president Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi took power in Egypt in May 2014, critics have accused him of using the law and the courts to criminalise opposition to his regime. They say he is taking extreme measures to grant himself powers similar to those held by former ruler Hosni Mubarak during the 30-year state of emergency that marked his rule. On August 16, 2015, Mr Sisi approved an “anti-terrorism law” setting up special courts empowered to impose the death penalty on anyone found guilty of establishing or leading a terrorist group. The new law allows the trials of suspected terrorists to be fast-tracked through the special courts. It includes heavy sentences for anyone found guilty of financing a terrorist group, as well as anyone deemed to have joined a terrorist group, incited violence or created a website publicising terrorist messages. Mr Sisi says the new law is necessary to the state’s efforts to contain Islamist and jihadi groups that carry out attacks and assassinations on Egyptian soil.

“The hand of justice is shackled by the law,” he said on June 30 in Cairo at the funeral of the country’s prosecutor general, Hisham Barakat, killed in a car bomb attack in the Egyptian capital the day before. He added that the law would be amended as soon as possible to allow the Egyptian state “to implement justice”. Mr Barakat had been involved in the prosecutions of many figures belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist organisation. Earlier in 2015 Mr Sisi blamed the group for bombings in the country’s Sinai desert. The new law, which consists of no fewer than 55 articles, defines a “terrorist act” as “the use of force, violence [or] threats” with the aim of “disturbing public order”, “harming national unity”, “damaging the environment, natural resources, monuments, public and private entities”, or “obstructing the work of public institutions, local councils, diplomatic missions, and places of worship from carrying out their work whether wholly or partially”. But critics say this view of terrorism is too broad. “Almost anybody can be a terrorist … under [this] definition,” says Frances Shealy-Salinié, Egypt coordinator for Amnesty International (AI) in France.

In 2014, on the third anniversary of the January 25 Revolution, for instance, 19-year old Mahmoud Mohamed Hussein happened to be wearing a T-shirt with the slogan “A nation without torture” on it. He was arrested on his way home from a protest against both military rule and the Muslim Brotherhood in downtown Cairo. Some 600 days later, the 19-year-old student is still being held and has yet to be charged or tried for any offence. According to a letter written by his brother Tarek, posted on AI’s website on June 12, 2015, he was beaten and given “electric shocks to the face, back, hands and testicles” in an effort to extract a confession to having links with the Muslim Brotherhood. Cases like Hussein’s are legion. The Egyptian authorities have detained about 40,000 people since Mr Sisi came to power, both AI and Human Rights Watch (HRW) say. Many of the detainees are being held in administrative detention while they await trial, which could take months, the human rights organisations add.

In one case, an Irish-Egyptian teenager, Ibrahim Halawa, has been held in an Egyptian prison since August 2013, when he was arrested along with hundreds of others at a protest at the Al-Fath mosque in Cairo. AI Ireland severely criticised the “lack of due process in Egypt”. “There are a lot of innocent people in [Egypt’s] prisons,” an Egyptian judge told Africa in Fact, speaking on condition of anonymity. “But people say in the end we are fighting terrorism, so when you’re fighting terrorism, these things happen.” Most of the people arrested are charged with belonging to the banned Muslim Brotherhood group. According to a local newspaper, Daily News Egypt, about 3,977 people were arrested in the first five months of 2015 on charges of belonging to the Brotherhood. Other groups are also being targeted by the courts. In April 2014 the Court of Urgent Matters in Cairo ordered the banning of the activities of the April 6 Youth Movement over espionage claims. The movement, a civil society activist group that played a key role in the 2011 uprising against former president Hosni Mubarak’s regime, is now facing a criminal lawsuit that calls for it to be labelled a “terrorist organisation”.

The new law also affects the media. Journalists face a minimum fine of 200,000 Egyptian pounds (about $25,000) and a maximum of 500,000 Egyptian pounds (about $64,000) if found guilty of “intentionally publish[ing] false news about terrorist crimes that are different from official statements”, for instance. At least 18 journalists are being held in relation to their reporting in the country, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a New York-based NGO that works to promote press freedom worldwide, says on its website. This is the highest number of journalists to be detained in the country since the CPJ began recording data on imprisoned journalists in 1990, according to the organisation. Media outlets such as Al Jazeera and the Turkish Anadolu news agency have been banned from operating or forced to close their offices. In July, the Egyptian Journalist Syndicate issued a statement saying that the new law was “contrary to the constitution” and that it was aimed at diminishing “the freedom of the press”.

On September 23rd, Mr Sisi pardoned 100 prisoners, including three Al Jazeera television journalists, on the day of the Muslim feast Eid Al-Adha, just before heading to the 70th session of the UN General Assembly of world leaders. The pardons, reported both by security sources and Egyptian media, included prisoners who had violated a 2013 law banning protests without a permit, including those with medical conditions and the elderly. The new anti-terrorism law also assigns certain judicial powers to the office of public prosecution. Under article 41, for example, public prosecutors investigating “terrorism” offences have the authority to investigate judges, which empowers them to order the pre-trial detention of individuals for an initial period of 15 days, which can be renewed for up to 45 days. They are also vested with the authority of a misdemeanour court of appeals, which can renew pre-trial detentions for even longer periods. It is an open question whether the judiciary can maintain its independence in the face of the new law.

“The judicial system is … getting more centralised, more oriented by the politics of the executive,” according to the judge referred to earlier. “Under Mubarak, there was kind of a movement asking for independence, and this movement is dead. It ended because the massive amount of politics involved in the judiciary is one of [our] problems.” Mr Sisi’s critics agree in likening his regime to that of former dictator Hosni Mubarak. “In some cases, the [new antiterrorism] law … is worse than the old one,” says Joe Stork, a deputy director of the Middle East and Africa division of Human Rights Watch. Mr Stork also points to an apparent lack of policing accountability. At least 1,400 people, many of them supporters of Mr Morsi, were killed in a crackdown on protests after his overthrow. Though official statistics are not available, few police officers and soldiers have been tried for their role in the repression of the protests or for later arrests. The anti-terrorism law is not the only potentially repressive piece of legislation passed by the Egyptian president this summer. Egypt has had no parliament since June 2012, when a court dissolved the democratically elected chamber.

In its absence, Mr Sisi holds legislative authority. And since his election in May 2014, in little more than a year, he has passed dozens of laws by decree, including new election laws. In July 2015, he signed an amended law that redefined the country’s voting districts, making way for parliamentary elections, which will lead to the country’s first legislature since the Muslim Brotherhood-dominated parliament was dissolved in 2012. An earlier version of the law was declared unconstitutional by Egypt’s Supreme Court on the grounds that it did not guarantee equal representation for voters. Critics of the new law say it favours individual candidates, rather than a system of proportional representation and party lists. They fear it will give victory to people or parties competing to provide support for Mr Sisi. New parties that have emerged from the popular revolution against former President Hosni Mubarak in early 2011 say they have limited or no financial resources, according to Khaled Dawoud, spokesperson of the Al-Dostour (Constitution) Party.

“They complained that they cannot compete in the elections if 80% of parliament’s seats are to be contested by individuals, most of whom can spend money heavily or have strong tribal and family ties, particularly in rural provinces and southern Egypt,” he says in a paper published by the Carnegie Endowment Fund for International Peace, a foreign policy think-tank. The combination of the new antiterrorism law with the new electoral districts law will strongly reduce the likelihood of free elections, political groups and human rights organisations say. “If you can’t stage a peaceful public protest, if you can’t have freedom of assembly, it’s very difficult to have free elections,” says Mr Stork. Laws against assembly were used during the presidential polls that saw Mr Sisi elected as well as during the referendum on the new constitution to prevent opponents of the new president from mobilising, he adds. “Just opening your mouth to say something fairly innocuous could result in you facing the death penalty or imprisonment,” says Ms Shealy-Salinié. “In 2011 people went onto the streets to ask for bread, justice and liberty. But they haven’t gotten any of those things, have they?”