Dynastic politics and a one-party state

Togo held its first multi-party election polls in 1958 under United Nations supervision, before gaining independence from France in 1960 under the leadership of Sylvanus Olympio and his Committee of Togolese Unity (CUT), who had won the elections two years earlier. Then in 1961 Togo became a republic, with Olympio as its president, raising people’s hopes that these events signalled an era of stability for the country.

Those hopes, however, were short-lived, as the country experienced a wave of political repression, leading to the detention of activists, the dissolution of opposition parties and the creation of a one-party state. It was against this background that a group of Togolese military returnees from the French army, including a sergeant, Gnassingbe Eyadema, staged a coup d’etat in 1963 and assassinated Olympio. These events were two firsts for post-independence Africa – the first coup and the first assassination of an elected leader.

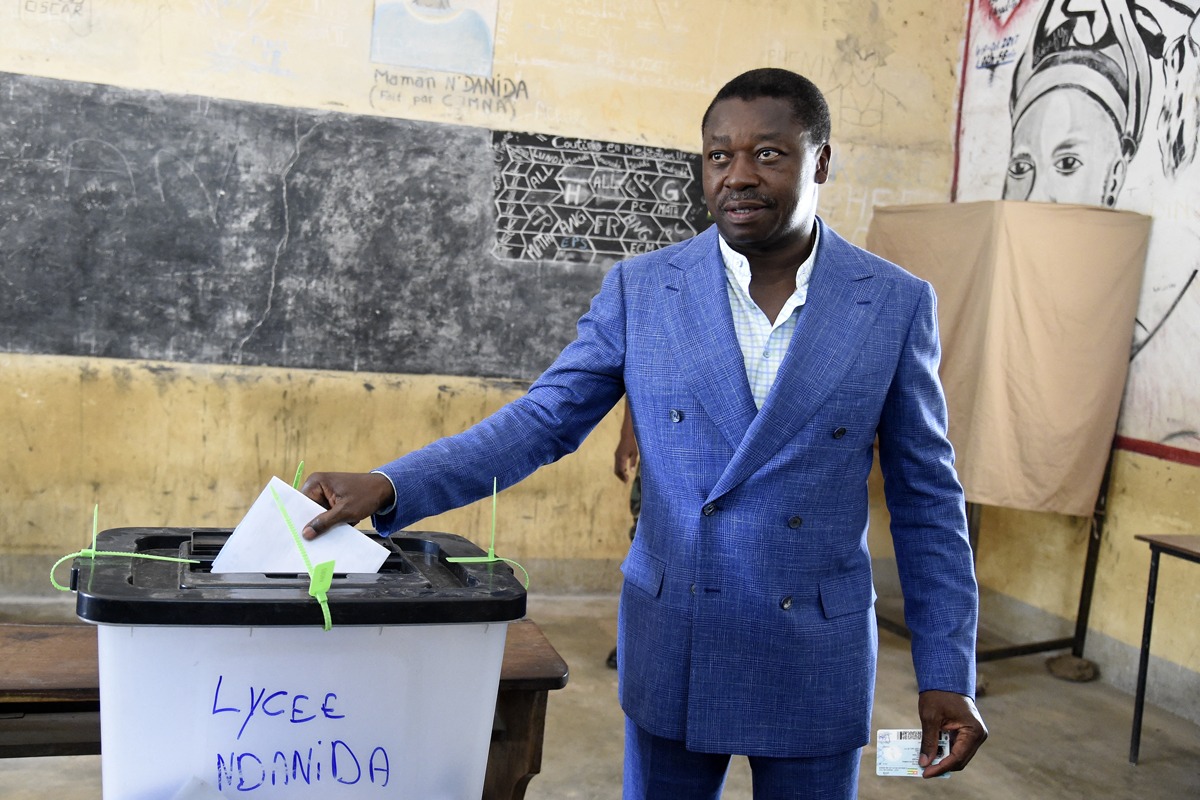

An electoral officer holds up a ballot paper at a polling station in Lomé on 22 February, 2020 during the presidential elections. Photo: Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP

The military took over the country, installing a civilian, Nicolas Grunitsky, as president. Eyadema took power himself in January 1967, banning party politics and creating a one-party state.

Despite a return to multi-party politics in the early 1990s, following protests against Eyadema’s authoritarianism, the Gnassingbe family has remained in power for more than five decades. Eyadema and his son, the present incumbent, Faure Gnassingbe, have won seven elections between them since 1993 amid ongoing opposition claims of systematic election fraud and wielding undue influence over Togo’s electoral commission, the judiciary and the army. To all intents and purposes, Togo remains a one-party state, say observers.

What appeared to be a simple strike by students asking for better study conditions in October 1990, ultimately set the pace for the return of multi-party democracy when, faced with growing unrest, Eyadema legalised political parties and agreed to multiparty elections. The manifest desire for better living conditions through political change was punctuated by violent confrontations between pro-democrats and supporters of the regime. To date, hundreds of people have died in the struggle for democratic change in Togo.

Eyadema’s own rule came to an end when he died suddenly in 2005. The military wasted no time in installing his son Faure as president in an election characterised, like the others, by irregularities and violence against the opposition.

Since then, Gnassingbe has won four presidential elections, the latest in February 2020, in which, according to the electoral commission, he received 72% of the vote, an outcome that was widely disputed. The main opposition leader, former prime minister Agbeyome Kodjo, who came second despite expecting to win and who demanded a recount, fled into exile. A Togolese court has since issued an international warrant for his arrest.

Togolese president and candidate of the ruling Union for the Republic (UNIR) party Faure Gnassingbe casts his vote at a polling station in Kara, on 22 February, 2020, during the presidential elections. Photo: Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP

The country’s constitution, which was voted for by 97% of the electorate in 1992, remains at the heart of Togo’s current political turmoil. Faure’s father amended the constitution in 2002 to allow himself unlimited terms of office. Since then, Togolese have been demanding a return to two-term limits, with tens of thousands of people taking to the streets between 2017 and 2019 to demand reform. Bowing to pressure, in 2019 the Gnassingbe government proposed a constitutional amendment to return to two-term limits, but only with effect from 2020, which means that he could remain in power until 2030. This proposal was rejected by opposition parties.

The international community’s silence on the phenomenon of “third termism” has been criticised by opposition leaders, who have accused the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), of which Togo is a member, of turning a blind eye to Gnassingbe’s tampering with the constitution to retain power for his clan.

“If nothing is done, any elected leader could easily change our constitution, either to limit or extend the presidential term,” Dodji Apevon, a lawyer and leader of the opposition party FDR says. “It is against the rule of law. We must have a sacred, untouchable constitution.”

In a review of last year’s election, published in March 2020 by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Alix Boucher noted that “more than 70% of Togolese told Afrobarometer in 2017 that a two-term limit should be reinstated in the constitution and that Gnassingbé should not run again in 2020, having already served three terms. Moreover, almost 80% of Togolese say they disapprove of the government’s handling of the economy.”

Citizens, Boucher wrote, also had little trust in the government: “more than 80% of Togolese say the presidency, parliament, police and judges are corrupt, revealing deep levels of mistrust in government institutions. Similarly, more than 70% of the population does not see the National Electoral Commission (CENI) as a non–partisan, technical institution.”

Until recently, Togo’s economy was doing well, with annual growth of 5.3% in 2019, according to a November 2020 World Bank overview. Growth was driven by an increase in public investment, expansion in the construction sector, and improved agricultural productivity, the bank said, although the services sector was the main driver of growth due to expanding port and airport operations. However, the crisis triggered by the global coronavirus pandemic was expected to lead to a decline in growth to 1% in 2020.

However, analysts also point out that regional inequality within the country is a concern, with more than 55% of Togo’s people living below the poverty line, 69% of them in rural areas.

“Management of the country is calamitous. Politics has divided us, and the regime has put in place an obsolete but authoritarian system to maintain power against the will of the people,” Apevon says.

However, despite the accusations against the government from civil rights organisations, Gnassingbe supporters question whether opposition leaders are in a position to take the helm.

“They easily accuse the regime of using an authoritarian system to remain in power, but what are opposition leaders proposing as alternative development programmes? They keep calling for political change, but they must also show the people that they have development programmes for the country. That is what our leader has done for some years now,” says Charles Kondi Agba, dean of the executive bureau of the ruling Union for the Republic (UNIR) party.

Agba also appealed to opposition leaders to not simply try to duplicate western systems of government, “because concepts vary from one geographical space to another”. “It has taken a lot of time for European countries to be where they are today in terms of the democratisation process. We have our culture, and our realities are different. The experience of violence, blood-letting and ethnic wars in other parts of Africa shows that the democratisation process must be a gradual process when applied in Africa, where often the machinery of a one–party state has existed for more than three decades following independence. Let a child first learn how to crawl before he can walk steadily.”

However, as analyst Léon Amouzou notes: “The last constitutional amendments were made without seeking the approval of the people through a referendum. The head of state used the ruling-party dominated parliament to unilaterally amend the constitution that his father had already amended in 2002, to stay in power for life. If there were ethical rules in politics, the incumbent head of state would not have stood for a fourth term, showing that he respected the will of the people.”