A house destroyed by flooding in Niamey, Nigeria, on 3 September 2019. Flooding is one of the climate change-induced disasters that are occurring more frequently in parts of Africa. Photo: Boureima Hama/AFP

Over the past two decades, countries have battled to reach meaningful multilateral consensus on reducing carbon emissions at international climate change negotiations. Globally, climate action strikes have increased dramatically, particularly among young people, who call for a more urgent response to climate change impacts. The science is clear, but our governance systems are struggling to keep up with necessary policy creation and implementation.

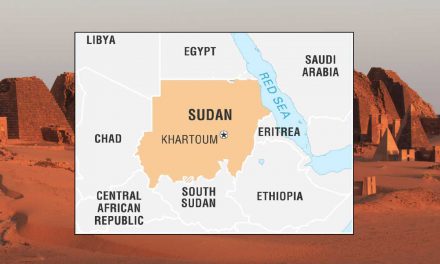

Climate change-induced disasters are beginning to occur more frequently and have already been especially devastating on the African continent. These include severe drought in Kenya and Madagascar, intense desert locust invasions across East Africa, desertification across the Sahel, more frequent cyclones off the coast of Mozambique and record-breaking floods in Sudan, to name a few. These events have had a major impact on food security, conflict, and poverty.

Coupled with the economic hardship brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, climate-related disasters will only worsen the socio-economic state of the region. The upcoming 26th annual Conference of Parties (COP26) comes at a crucial moment, because unless CO2 emissions are dramatically reduced by 2030, the planet is likely to experience at least a 1.5-degree warming (above pre-industrial levels) by 2040.

Transnational governance is the involvement of state and non-state actors in collective processes and institutions that formulate rules, both formal and informal, to elicit compliance in the pursuit of collective goals. Climate change mitigation is but one example of transnational governance that requires the compliance and agency of regional blocks, states, cities, corporations, civil society, and individuals. Why? The challenge of climate change mitigation necessarily involves actors from all levels of society. Transnational governance provides states and sub-state actors with a platform to share and discuss solutions, technologies and knowledge on climate issues that can inspire innovation and create change where necessary.

Transnational climate governance versus state-based climate policy

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) acts as the foundation on which transnational climate governance rests. It provides a system through which states and non-state actors formulate strategies and tools for the mitigation of climate change impacts. Transnational climate governance has emerged as an alternative approach to the traditional state-based governance of international climate negotiations. Experts argue that cities, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), businesses and other non-state actors have become key players in transnational climate governance. The growing role of sub- and non-state actors in climate initiatives, activism and networking facilitate an alternate governance strategy that challenges the traditional state-led nature of global governance. Even so, there is doubt as to whether their role is sufficient to meet the mitigation and adaptation policy needs of countries worldwide.

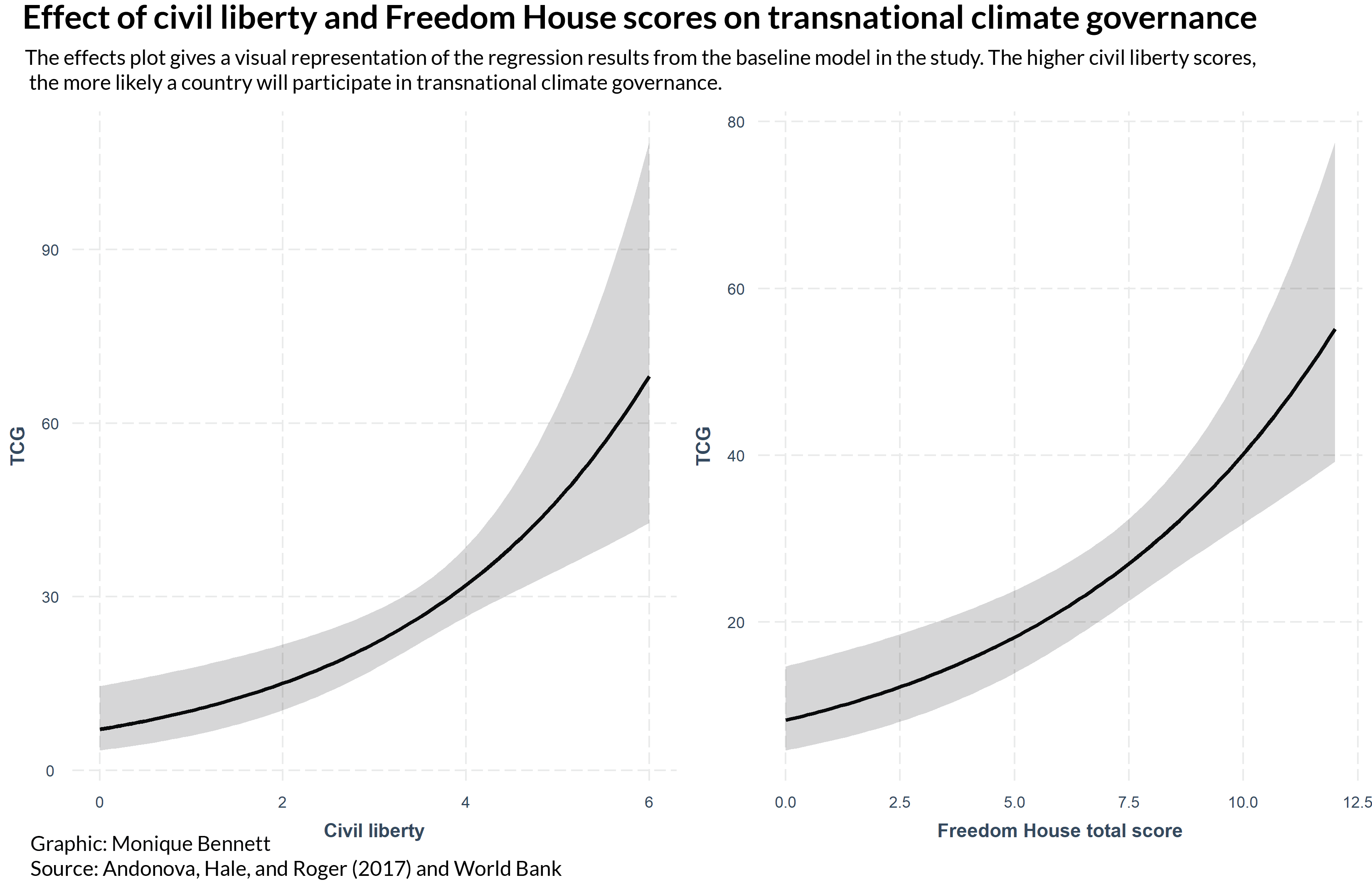

Transnational climate governance combines the efforts of private and state actors to unify their scope and influence, bringing together multiple networks and industries. The question I sought to answer investigates the trend of climate change governance and whether there is a reinforcing or subversive relationship between national climate policies and transnational climate governance (see my full article here). This was derived from an article from 2017, by Andonova, Hale, and Roger.

The authors argue that established national policies incentivise sub- and non-state actors to participate in complementary forms of transnational governance because they can assist transnational actors to meet domestic policy requirements. Finally, I examine whether the more democratic political institutions and state policies influence the likelihood of participation in transnational governance. The latter question is crucial in the context of democratic recession on the African continent, which already faces capacity issues as many governments begin operationalising national climate strategies.

Substitutes or complements?

Existing literature points to two mechanisms that influence the adoption of transnational agreements, one being domestic societal pressures and the other being international diffusion processes. The study’s results provide evidence to support the importance of these mechanisms at play between domestic political structures and the agency of sub and non-state actors in transnational governance. The results suggest that national policies and transnational initiatives reinforce one another. Furthermore, they help provide clarity on the politics of participation that are discussed in existing case-orientated literature.

The European cases within the sample exaggerated the relevance of open institutions and pro-climate policies in the analysis, cutting a clear North-South divide. The progressive coalition between environmental departments across the European Union (EU) region was supported by domestic political incentives due to the strong public support for climate change mitigation. The EU negotiating position was ultimately held by the respective environmental departments of the member states.

Less democratic states such as China show a different pattern in transnational climate governance participation that can be partially explained by the study’s results. China, a country with restrictive civil rights and institutions, has ambitious state and business policies related to clean energy and carbon markets. This has translated into a relatively high level of participation, with selective backing from the central government. The electric motor vehicle market is dominated by China, and its solar industry is steadily growing to help curb the state’s dependence on coal.

China’s involvement in transnational climate governance cannot be overstated, as it remains one of the biggest global emitters despite significant domestic pressures to clean up its environment. International actors should therefore make every effort to persuade the Chinese Communist Party to attend COP26, as rumours have started to surface that Xi Jinping will bunk the meeting. And while China’s participation hitherto in transnational governance is relatively high for an undemocratic state, democratisation would clearly strengthen the country’s national commitment at the global level.

Transnational climate governance in Africa

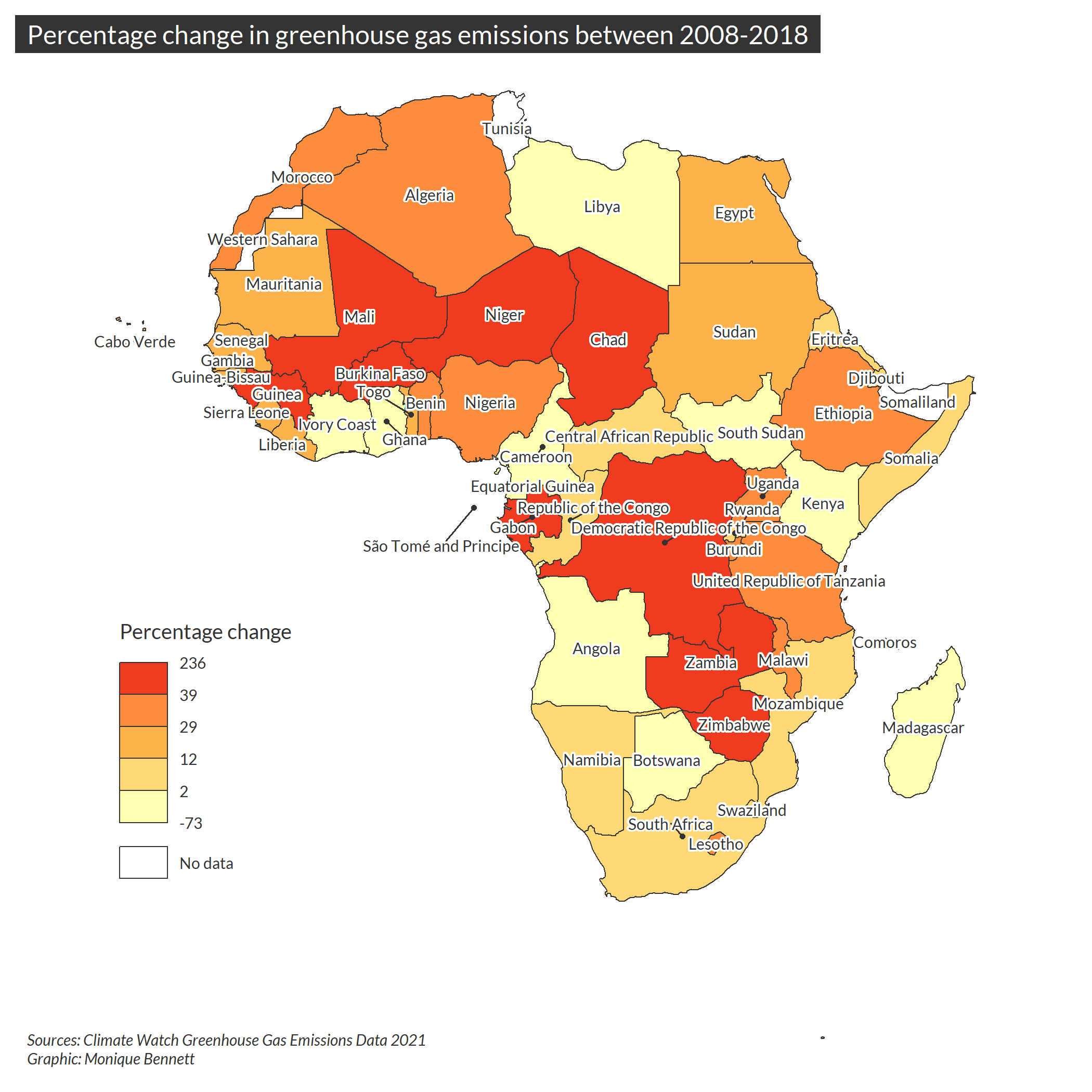

Kenya and South Africa are the only two African states that feature in the top 30 instances of transnational climate governance participation. Much of the existing literature regarding Africa and climate change centres around current and future impacts. Despite the continent’s minuscule collective contribution to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, it remains the continent most vulnerable and the least prepared for its effects. Despite this, the landmark Paris Agreement was overwhelmingly endorsed by African states with all 54 countries signing the Agreement.

African GHG emissions are expected to rise by 30% over the next decade at current continental population and urbanisation growth rates. The majority of the continent’s emissions are produced by it’s top 10 most developed economies: South Africa, Libya, Morocco, Kenya, Egypt, Algeria, Ethiopia and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Between 1990 and 2017, the population and carbon intensity on the continent increased by 97% and 47% respectively. The net increase in total emissions was 120% in the same period.

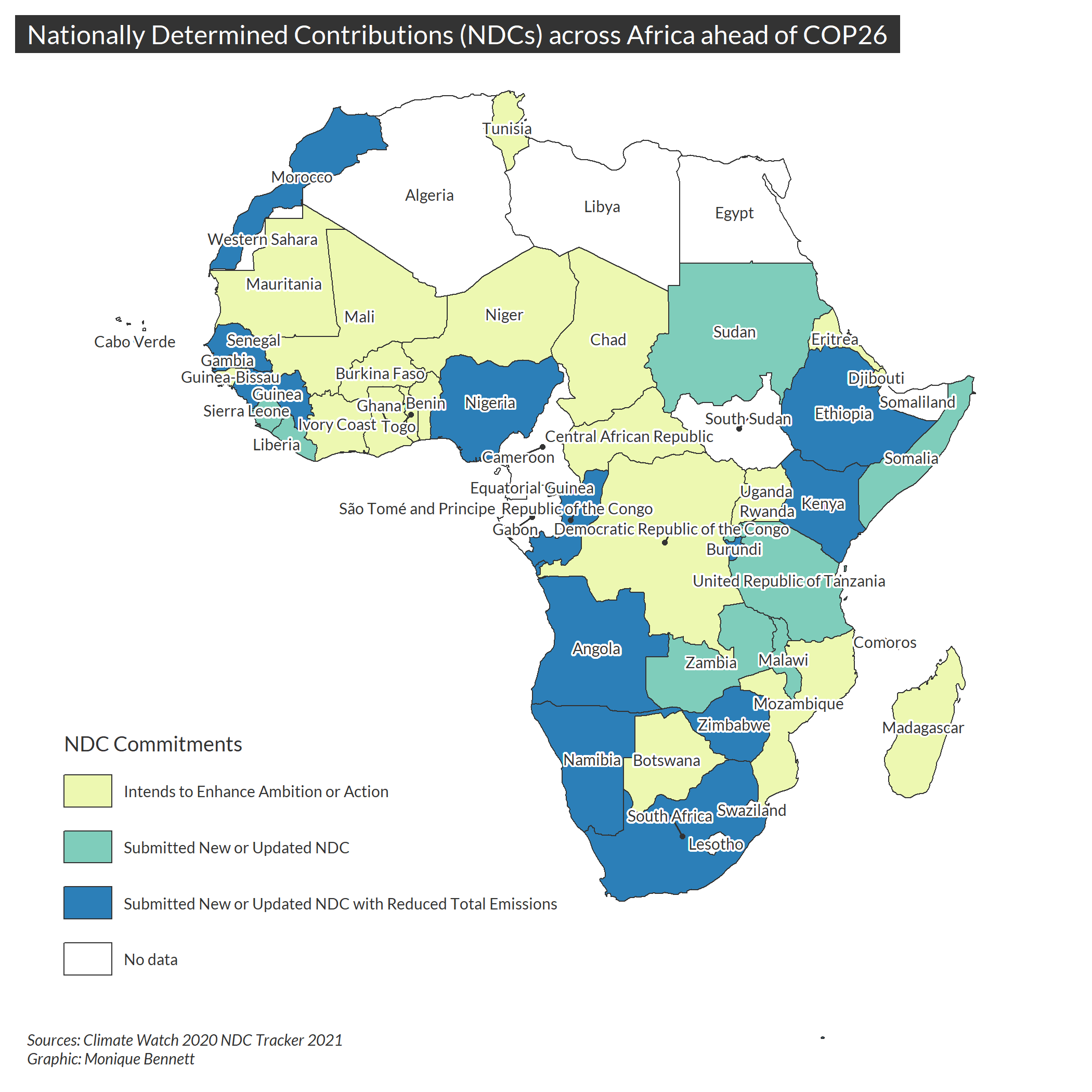

Africa’s NDC ambitions

In 2020, as part of the Paris Agreement’s ratchet mechanism, signatories were required to submit updated national plans highlighting targets for GHG emissions reductions and related policies to address climate change, called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The NDCs still essentially lack any accountability mechanisms for those who fail to meet their stated reduction ambitions. Only 44 countries (28% of global emissions) have stated an intention to enhance their action against climate change through their new or updated NDCs. Major absences include the United States, China and India. The advent of COVID-19 forced the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to delay the annual Conference of Parties (COP), which will now take place in Glasgow at the end of October 2021.

In 2017, the African Development Bank and its partners helped establish the African NDC Hub to provide support for effective implementation of national NDC ambitions across the continent. The African NDC Hub released a gap analysis report detailing recurring themes which would affect the ability for the continent to successfully implement their national NDC commitments. Lack of financial resources, technical capacity, and technology infrastructure were recurring themes identified as gaps in national NDC adaptation and mitigation policies. As a starting point for this year’s COP26, it’s critical to understand African countries’ past policy performance as well as current policies, to accurately predict what we can expect from them in the next decade. Beyond COP26, regional organisations across the continent must prioritise addressing the concerns facing their member states and ensure that the climate finance provided is appropriately and transparently allocated.

Angola – Better late (with ambition) than never

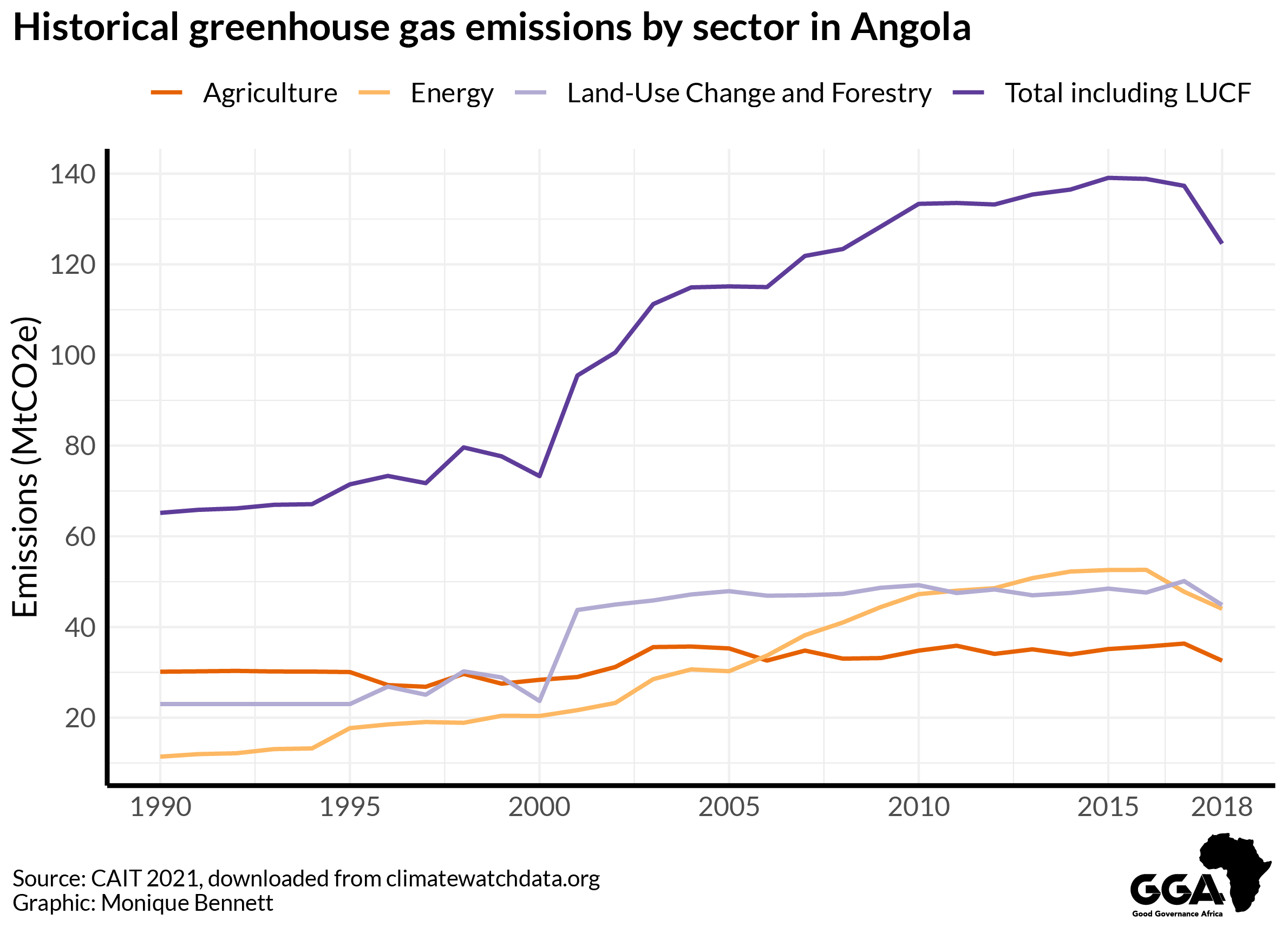

In August 2020, Angola’s foreign affairs minister announced that parliament unanimously approved the country’s ratification of the Paris Agreement. Angola is the second largest oil producer in Africa and more than 90% of its exports consist of crude oil. The resource contributes towards half the country’s gross domestic product, making it incredibly dependent on it. The impacts of climate change are ever-present in Angola, with significant temperature warming over recent decades. On average, the country has seen a rate of 0.33˚C warming per decade, with a simultaneous decrease in mean annual rainfall. The IPCC RCP4.5 scenario predicts that the country could witness an annual temperature increase of 1.2˚C to 3.2˚C in 2060, increasing the intensity of extreme weather events.

Angola submitted its first NDC in May 2021, acknowledging its vulnerability to climate change and the need for a commitment to reducing its GHG emissions. The country has committed to unconditionally reduce its emissions up to 35% by 2030 and an additional 10% conditional reduction. These targets are some of the most ambitious on the African continent. The country’s hydrocarbon industry, alongside its change in land-use and forestry, contribute the largest volume of GHG emissions collectively.

Giza Martins, director of the Climate Change Office of the Ministry of the Environment, explained that the aim is to transition the country’s energy sector towards hydroelectric plants and solar energy systems. By 2025, the goal is to reach 70% renewable capacity, according to the Ministry of Energy and Water. Earlier this year, Hitachi Energy and Sun Africa announced the development of Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest solar photovoltaic (PV) project, to be constructed in Angola. The site in Biopio, Benguela will help electrify over 230,000 homes. Over the past decade the country has invested USD 17 billion into its renewable energy sector. These renewable energy projects align with Angola’s ambition, however there is scepticism as to whether the projects can be completed on time.

One of the major challenges in measuring Angola’s past, present and future GHG emission inventory is the lack of accurate and consistent data. This lack of data makes it impossible for Ministries to effectively track the implementation of its NDCs. Data remains crucial if the country is to accurately strategise its proposed NDCs and mitigate the current risks already posed by the environmental changes witnessed over the last decade. Consistent data collection would assist in informing broader climate finance and capacity building needs, without which the assistance needed will not be adequately informed.

Ultimately, both transnational climate governance initiatives as well as strong national environmental policy are required for the world to effectively reduce GHG emissions. The rate of decarbonisation currently is not enough, and countries both in the developed and developing world have an obligation to act on what the science has revealed. Previous climate agreements have not created enough incentives to drive low-carbon investment, nor have they developed an adequate global carbon pricing system that is harmonised at a sufficiently high price and committed to by a broad swathe of countries. Finally, effective state-level implementation of climate agreements remains limited because the cost of free-riding on the efforts of others remains low. These three issues need to be urgently addressed if COP26 is going to have any meaningful effect in moving the world towards a net-zero economy by 2050.