The death of a 14-year-old girl, Anna Machaya, while giving birth in 2021, sparked national outrage and put the spotlight on the practice of child marriages within Zimbabwe’s Apostolic church, which also often rejects medicine and hospital treatment. Machaya died while giving birth in July last year at the Johanne Marange Apostolic Church shrine.

Machaya was married to one of the church’s members, 26-year-old Hatirarami Momberume. After her death, a petition against child marriage garnered thousands of signatures, and many campaigners hoped her case would expose the practice, which is outlawed in Zimbabwe but has continued despite threats of legal action.

Child rights campaigners say Machaya’s death was just one of the many cases – most of which go unreported – that are a consequence of child marriages in the country. The practice of child marriage is widespread in townships and rural Zimbabwe, where most of the country’s poor live, and where parents often say they’re forced to give away their young daughters in marriage to reduce the financial burden of their upkeep.

But the Apostolic church, especially, has come under scrutiny as young girls are encouraged to marry older men for “spiritual guidance”. Roughly one-fifth of Zimbabwe’s population of 15 million people belong to Apostolic sects, according to the country’s 2022 Zimstat census. Illegal marriages are condoned within church circles, and the government turns a blind eye.

A member of the Zion African Apostolic Faith Church sect folds his robe after worshipping in isolation on a hill in Matshobana township in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

The government has tried to curb child marriage, but half-heartedly, because the ruling Zanu PF’s largest number of voters are Apostolics. It is in this context that NGOs are trying to force the government to enforce the law that forbids child marriage. However, Zimbabwe will be holding elections in 2023 and critics claim adults who arrange child marriages rarely get prosecuted because sects like the Marange church have a lot of political power.

Nyasha Marange, a spokesperson for the Johanne Marange Apostolic Church where Machaya died, said the church frowned on marriages involving children under 18 years. “Our church members do not abuse minors; our leaders have been preaching against that,” Marange told Africa in Fact.

But Machaya’s death has renewed calls from civil society for the Zimbabwean government to crack down on religious sects accused of institutionalising sexual abuse and marriage of girls to older men.

“As a policy, any member of the church who engages in child marriage is immediately out. We applaud the government for laying criminal charges against Momberume for his deed, and this is a warning to any other men who intend to follow the same route,” Marange told Africa in Fact.

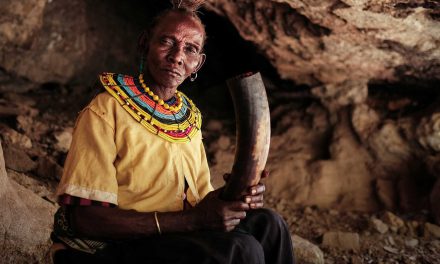

An Apostolic Church member prays in an open field in the Mbare township in Harare, in July 2018.

According to the campaign group, Girls Not Brides in Zimbabwe, more than a third of the country’s girls are married before the age of 18, while 5% are married before their 15th birthday. In addition to religious practices, poverty, drought, and cultural beliefs have also been cited as major drivers of child marriage. A recent survey by the United Nations Population Fund reported that Zimbabwe was among 41 nations with the highest rates of child marriage.

The organisation also told Africa in Fact that one woman in four aged 20 – 24 years in Zimbabwe had given birth before the age of 18. This situation has worsened since the implementation of Covid-19 restrictions, including mandatory school closures, when Zimbabwe recently experienced an increase in teenage pregnancies.

Between January and 5 February this year, nearly 5,000 teenagers fell pregnant, while 1,174 child marriages were recorded, Zimbabwe’s Women’s Affairs Minister Sithembiso Nyoni told the country’s parliament in March. She said officials were collecting data on teen pregnancies, adding that rural areas were the most affected, and called on authorities to act against churches abusing teen girls.

“We are saying all those churches abusing children should be brought to book. We want churches, which start things in the name of God, to be responsible and not abuse children,” Nyoni said.

But Kudzai Biri, a Zimbabwean-born professor at the University of Bamberg in Germany, says the fight against child marriage is a losing battle because of the close relationship between politics and religion. Sects like Marange enjoy political protection in exchange for votes, she says, a practice former president Robert Mugabe normalised and that has continued under the incumbent, Emmerson Mnangagwa. “They sacrifice social justice for political gain,” Biri told Africa in Fact.

Mnangagwa has addressed congregations of Marange worshippers at the invitation of the sect’s former leader, the late High Priest Noah Taguta. The president has also attended mass gatherings held by Apostolic sects.

Members of the African Apostolic sect wait to view the body of the late Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe during a public send off at Rufaro stadium in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Meanwhile, in the eastern border town of Chipinge – some 446 km east of the capital, Harare, early marriages have reached alarming levels, with reports of parents exchanging 10-year-old girl children for food because of successive cyclone-induced droughts. Chipinge is one of the areas hard hit by the drought, which has ravaged the southern African region. Claris Madhuku, the director of Platform for Youth Development (PYD) – a community-based organisation working to empower young women and girls – told Africa in Fact that recent research it conducted had recorded huge numbers of girls dropping out of school.

“Hunger has increased at an alarming rate in the past 12 months, with parents left with no choice but to give away their girl children,” he says. “In some areas, girls as young as 10 are being carried out. There are cases of parents taking the initiative to offer their daughters to well-off families.”

Chinga Govhati, a child protection advocate, told Africa in Fact that child marriage hurt Zimbabwe’s development because there were limited job opportunities for girls who married before completing their education. “Child marriage deprives children of their right to acquire appropriate skills to enter the labour force as adults and pushes them further into poverty,” she said. “Child marriage also increases the girls’ risk of domestic violence, psychological and physical violence, including sexual violence, and HIV infections.

“There should be political will to implement laws and processes that give life to legal developments that we have been seeing in the recent past,” Govhati added. “We have seen the enactment of the Marriages Act that criminalises child marriage or any act perceived to be exploitative in that regard. The challenges [is] full enforcement, making the law realisable for every girl despite the religious, social or cultural prejudices militating against the realisation of their rights.”

Jacqueline Kabambe, a United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Adolescents and HIV specialist, agrees, telling Africa in Fact: “The challenges include increased poverty, high unemployment rates, school dropouts, particularly for girls due to pregnancy or child marriages, drug and substance abuse, and risky sexual behaviour, increasing the risk of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, with girls three times more likely to be infected than males of the same age group of 10 to 24.”

UNICEF was leading a multi-agency national assessment of adolescent pregnancies in Zimbabwe, Kabambe said. “These include the Spotlight Initiative, focusing on social behavioural change and addressing social norms; working with parliamentarians to address issues of child marriage and the harmonisation of laws with the Constitution; strengthening early warning systems for the identification of children at risk so they are protected and [given]access to protection services; strengthening education systems to prevent and manage abuse and pregnancies, including supporting the reintegration of pregnant adolescents into the school system,” she said.